Owen Tucker-Smith, Contributing Photographer

After more than three decades of collaboration, the New Haven Police Department and the Yale Child Study Center released their trauma-informed police training toolkit that will now be adopted on the national level.

The program is designed to educate officers who often come into contact with trauma-affected individuals, particularly young children. Through the program, officers learn the psychological effects of trauma and how to identify symptoms through a method of questioning and observation. The center released its first child trauma curriculum in 2017 as part of a collaboration with the International Association of Chiefs of Police. Two years later, the NHPD implemented a training based on this curriculum, becoming the first police department in the nation to offer a training of this kind for its officers. Now, after approval from the IACP, the curriculum has become available online for police departments across the United States.

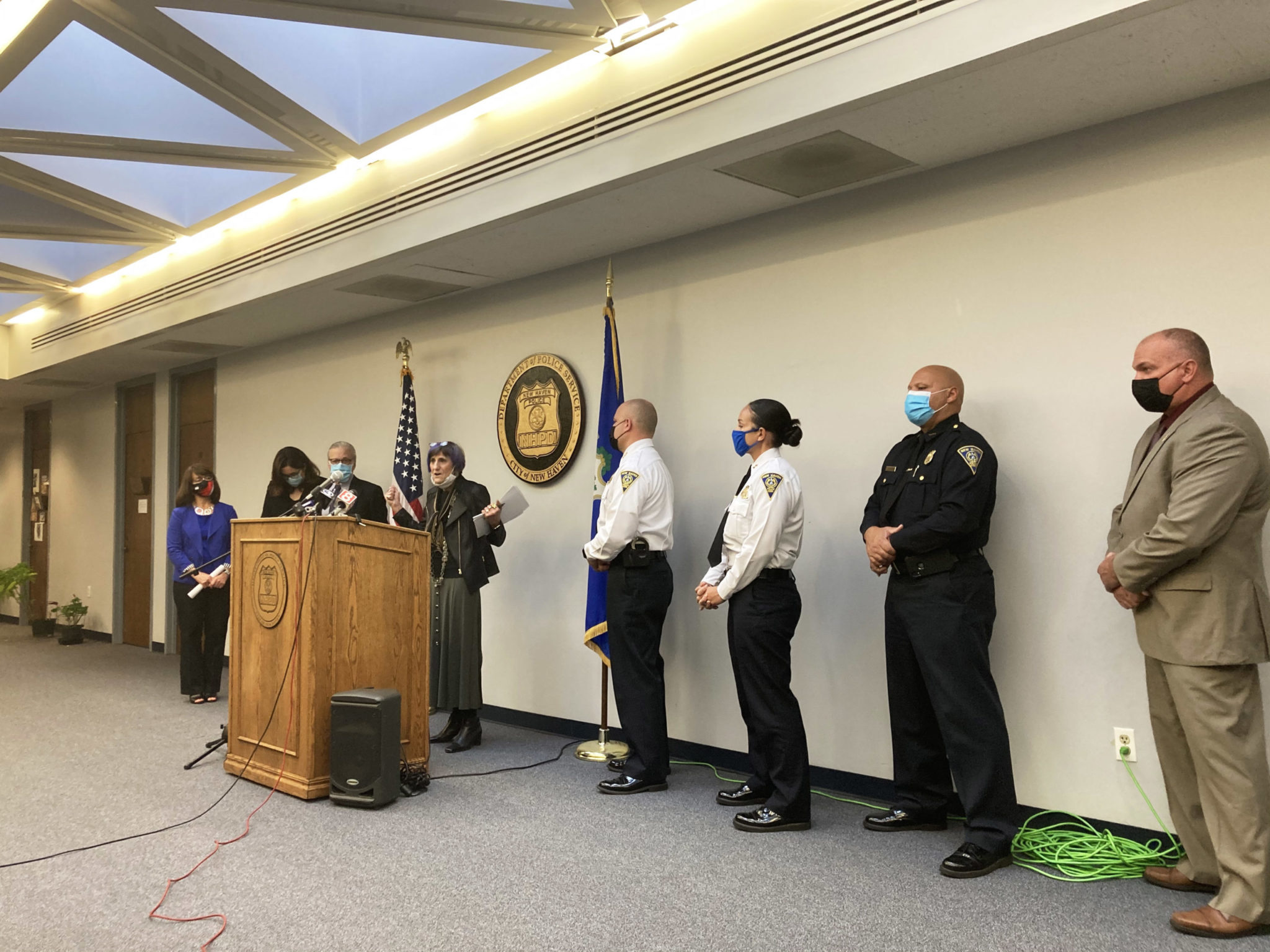

“This is exciting, because the IACP recognizes that this work is important to what we do with communities, and that police are actually well-positioned to better provide these services in conjunction with social service partners,” NHPD Chief Otoniel Reyes said at a Monday morning press conference.

At the press conference, Reyes said the program hopes to take advantage of the fact that officers are often the first ones to interact with children who have just experienced trauma. He added that the training has helped create a departmental focus on how officers can contribute to the recovery process of New Haven residents.

Since 2019, the NHPD has put all its officers through the training. In collaboration with the Child Study Center, the department has also certified 20 of its employees as curriculum trainers, eligible to train officers from other departments.

The curriculum, according to Childhood Violent Trauma Center Project Director Hilary Hahn, is “comprehensive” and covers a combination of how to understand trauma and how officers can use that understanding to interact with children and families. Hahn said the program begins with a Trauma 101 module that briefly explores the concepts of violence and trauma. It also instructs officers on the protocols they should use to respond to children who have been exposed to violence, such as avoiding interviewing or arresting parents in front of their children.

Although the program is focused on children, Hahn said it is meant to support anyone exposed to violence. This includes caregivers, who often need help coping with trauma themselves as well as caring for affected children.

Steven Marans, director of the Child Study Center’s National Center for Children Exposed to Violence, said at the press conference that the center’s research has repeatedly shown that interactions and connections immediately following traumatic experiences play a large role in long-term recovery.

Marans said the curriculum aims to help officers correct common misconceptions regarding children and trauma — for example, the idea that children would have to be demonstrating active distress following an incident to be designated as vulnerable.

“It used to be that if children were sitting watching television after a very violent event, they were doing OK,” Marans said. “This actually may be a silent symptom of traumatic dysregulation that makes their ability to engage in the outside world very, very compromised.”

The curriculum, he said, aims to prepare officers to be able to observe this dysregulation as a symptom of something more dangerous.

U.S. Rep. Rosa DeLauro, D-CT, who chairs the Congressional “Baby Caucus,” which focuses on issues impacting children, heralded the program’s nationwide release at Monday’s press conference. The Elm City congresswoman highlighted the program’s focus on an issue that can have “a long and lingering impact on children over a lifetime.”

“If we can prevent the suffering of young people, if we can empower our first responders to better heal their community, if we can divert children from hurt to health, then we must be doing that,” DeLauro said. “This toolkit empowers officers to recognize that they can do more than stop the harm — they can start the healing.”

The YCSC and NHPD first partnered in 1982.

Owen Tucker-Smith | owen.tucker-smith@yale.edu