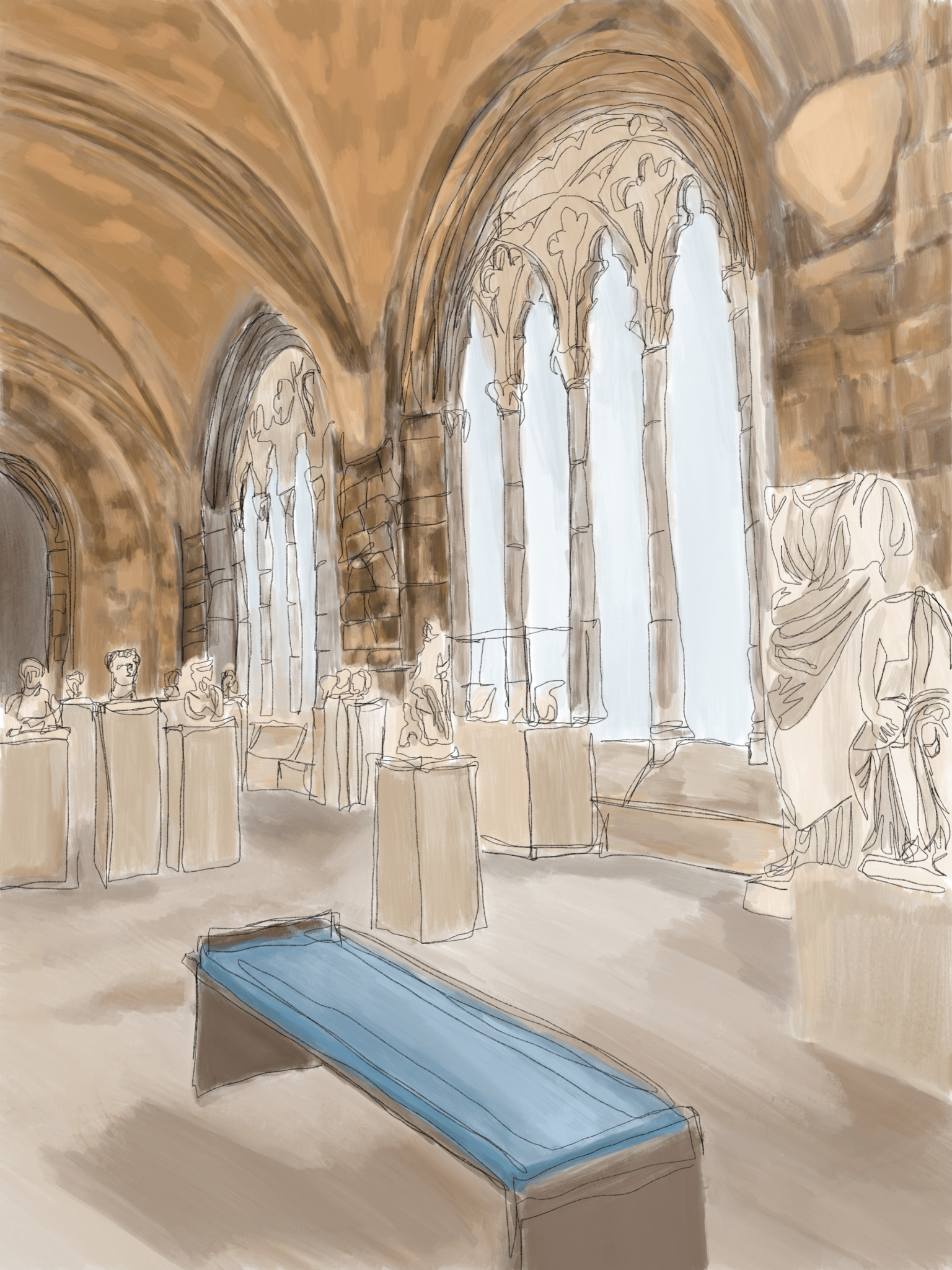

My friend and I entered the atrium of the Yale University Art Gallery and found ourselves surrounded by the numerous sculptures and statues. The light cast from the windows created an almost ethereal atmosphere as the hallway was lined with polished white stone statues and reddish-brown terracotta pots. As we stopped to look at them closer, we found ourselves having to lean over a red barrier that formed a boundary between us and the art. Squinting to read the placards near the sculptures, we were interrupted by a security guard who ushered us to keep walking. I told her that I was a first year and I had never been to the art gallery before and was wondering if this was what it was like under normal circumstances. Kindly but bluntly she answered. “No, not at all.”

On Sept. 25, the Yale University Art Gallery reopened for visitors after a six-month long closure due to coronavirus. Now open Friday, Saturday and Sunday, the gallery has adapted to the pandemic, providing a unique and unconventional experience to visitors.

Visiting the gallery on Oct. 11, I arrived not knowing what to expect. I had not been in a gallery or a museum since the pandemic hit, and I was interested in seeing how exhibitions had changed these past few months. Prior to my entry, I was greeted with an email in my inbox reminding me of my reservation and the procedure before entry. The email distinctly stated that latecomers would not be allowed into the museum and, in a fit of panic and fear of missing my spot, I got ready 30 minutes before my time and sat in the common room anxiously. I arrived at the gallery 10 minutes early with a friend and, surprisingly , we were allowed in. The check-in desk asked the same series of questions you almost always hear: “Have you had symptoms of coronavirus? Been in contact with someone with the virus? Tested positive?” Hearing these questions, I almost always wonder who is answering yes to them. Why would you even show up? I couldn’t think about it too much as my ticket indicated that I only had one hour to explore the museum.

Under normal circumstances in the gallery, there would be people leaning over red dividers, no marked-off exhibits and no need to squint to read captions. The security guard who spoke to my friend and I in the atrium informed us that our tickets only allowed us to view three of the special exhibits, nothing more.

We were led to the elevators and ushered to the fourth floor where the first of the three special exhibits began. It felt odd to pass by the lower floors, knowing you could not enter them and see the art behind the elevator doors. Regardless, we didn’t dwell too much on what we couldn’t see. I hadn’t been to a gallery in forever, so any chance I could get was a plus in my book. Our first stop was an exhibition titled “The Incident” by John Wilson. “The Incident” depicts Ku Klux Klan members lynching a Black man as an African American family watches from their window. The exhibit included not only a large floor to ceiling mural but also several sketches and studies on which the piece was based. Walking around the exhibit, I began to feel the familiar comfort of walking through a gallery. The stark images of Wilson’s work left me speechless and, for a moment, it felt like I was simply at an art museum, not at an art museum during COVID. This exhibit was well designed and showcased art that felt unfortunately relevant to our current time. In fact, an hour after visiting this exhibit, the student-organized Black Lives Matter demonstration took place on Cross Campus.

Due to the COVID guidelines, the museum was much emptier than it usually is. This has a profound effect in an art gallery, as the art stands out more. I could simply stand in front of the pieces and read the captions, not worrying about blocking someone’s view or getting in someone’s way. The emptiness, while not the most comfortable, made viewing the art more intimate.

As we left for the second exhibit, we were once again approached by a security guard, this time because we were going the wrong way. As obvious as the directional arrows were, it’s still difficult to not find yourself wanting to wander around. What better place to wander than an art gallery?

We then entered the second exhibit: “James Prosek: Art, Artifact, Artifice.” This exhibit was almost the opposite of the previous one in terms of style, as there were a variety of different mediums present in the collection. From taxidermied birds with drill bits as beaks, to twisted iron sculptures, this exhibit explored the intersection of art and artificiality. Once again, this exhibit was largely empty aside from me, my friend and a security guard. While I still felt close to the art as I did before, the emptiness provided an interesting experience. Everytime I talked about a painting or a work, it felt like I was screaming about it because the gallery was so quiet. Although galleries aren’t known for their loud and noisy atmospheres, before the pandemic you could almost always find the quiet chatter of museum goers bouncing around the walls. Now, in the echoing space, every analysis and comment felt as if it was going through a loudspeaker.

However, this changed with the last and final exhibit, entitled “Place, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 years of Indigenous North American Art.” Unlike the two earlier exhibitions, this one had more people, and the familiar quiet chatter reminded me of a time before COVID. The exhibit itself showcased a wide range of Indigenous art from intricate beadings to carefully crafted pots, the culture emanating from the art allowed me to feel closer not only to the works on display but to the others in the museum as well. After all, that is one of my favorite experiences of being in an art museum: to take part in a shared experience of consuming art. In a world of COVID, this sense of closeness is found in six feet increments but in this exhibit, I found that six feet was not as far anymore. I could overhear someone’s comment about a piece, and I could visit it right after to see if they were telling the truth. I would say, “Woah look at this” and, sure enough, a few people would overhear and find themselves in front of the piece a few moments later.

Once finished, my friend and I wished to revisit “The Incident” painting but were met with one more security officer informing us that we were not allowed to go back that way. And with that we headed into the elevator and looked at the map of all the exhibits that were in the museum. Luckily, before we left, the security guard informed us that they are trying to make more exhibits accessible to people and are considering opening up more floors in the coming weeks or months. I hope in addition to that, they are able to safely increase the number of hours we can be in the museum, as we were able to spend the full hour in just three exhibits.

It is jarring to be in a museum during a pandemic. The sheer gravity of living through such a monumental experience makes me think that one day I will enter a museum and see a Yale mask framed in a glass box in an exhibit on coronavirus. Yet despite how unsettling that feeling may be, it is largely outweighed by the fact that museums and galleries are able to provide a familiar feeling of closeness. During the pandemic, toilet paper and hand sanitizer were flying off the shelves, but art grants us an even rarer commodity: connection.

Aparajita Kaphle | aparajita.kaphle@yale.edu