Dora Guo: Inspired by @evanmcohen

Maria was my host mom while I took classes in Buenos Aires after my first year of college. She lived in the Recoleta district, on the top floor of a narrow, white apartment building with balcony columns shaped like hourglasses. Her apartment was a few blocks from Argentina’s national library — a towering, Brutalist structure built like an uneven stack of books. All the apartment buildings on her street were tall and white, but Maria’s had a golden door knocker and handle. Inside, a silver scissor gate guarded the elevator on the ground floor, which, with effort, collapsed like an accordion.

I carried three clunky gold keys everywhere so I could get in Maria’s building: one for the main entrance and two for the door to her suite. Maria lived alone. The suite opened to a living room like a dentist’s lobby, with white walls, a soft white couch and fashion magazines piled upon a glass table. Our bedrooms were smaller and less glamorous. My room, with its short twin bed and gauzy curtains, might have been cozy if it hadn’t been so cold inside. It was June — Argentina’s winter. I spent a lot of time sitting beside the space heater on the brown wool rug. In our shared, pink bathroom, I learned that you might say “disculpa,” not “lo siento,” to apologize for walking in on someone.

I always thought Maria looked a little like Mafalda, the Argentine comic strip character, if Mafalda had been taller, slimmer and around 60 years old. For many years, Maria was a journalist for La Nación, Argentina’s leading conservative newspaper. When I first arrived at her apartment, she asked, in slow, patient Spanish, all about my ancestry (mostly German, Jewish on my mom’s side), why I chose Argentina for summer abroad (mostly chance, the language and literature program) and what I like to eat (no meat, lots of vegetables and sweets). Maria cooked dinner every night: lots of vegetables and sweets and chicken at first, because pollo isn’t carne to her, and I wasn’t a strict enough vegetarian to decline it. We ate together in her little kitchen most nights. Maria threw her head back in laughter every time I made a vocabulary mistake in Spanish. Forgetting the word hielo (ice), I once asked for helado (ice cream) because my foot hurt after a run. Maria was just beginning to take English classes, so after dinner we helped each other with our respective language assignments.

Maria liked to sketch on maps for me before I went anywhere, underlining routes and circling her apartment. The maps were large, wide enough to cover both our laps when we sat together on the couch. They showed all of Buenos Aires: our district of Recoleta to the northeast, with Palermo, the city’s shopping, dining and clubbing center nudged against us to the west, and Caballito, where I took classes farther southwest. At first, Maria crossed out large chunks of Palermo for me to avoid. My friends often met in those areas to go out on the weekends. Eventually, Maria said she’d allow me to visit those places if I always walked with a friend. I found it both irritating and sweet that she worried about me in that way, like a mother, even though she’d have no way to enforce those rules. Many of my friends’ hosts never asked where they were going when they left.

One afternoon, I planned to meet friends at Cafe Tortoni, a famous cafe near the Plaza del Mayo. In the mid-twentieth century, Cafe Tortoni hosted “La Peña,” a group celebrating the arts and literature, welcoming visitors such as Jorge Luis Borges. Today, the cafe serves food and drink upstairs and hosts concerts and literature contests in the basement. Maria was excited to hear I’d try Cafe Tortoni’s churros and chocolate. She quickly sat down to sketch a route for me to get there via the Subte, Buenos Aires’ metro.

The Plaza de Mayo is home of the Casa Rosada, a baby-pink executive mansion in Italianate style, as well as the Metropolitan Cathedral with its Corinthian columns. There’s also the statue of Bolivian guerilla leader Juana Azurduy which replaced the statue of Christopher Colombus during Christina Fernández de Kirchner’s presidency. From there, the walk to Cafe Tortoni is only a few short blocks. But that afternoon, the walk took more than half an hour. The Plaza de Mayo is the most popular site for marches and rallies in Buenos Aires, and that afternoon was no exception.

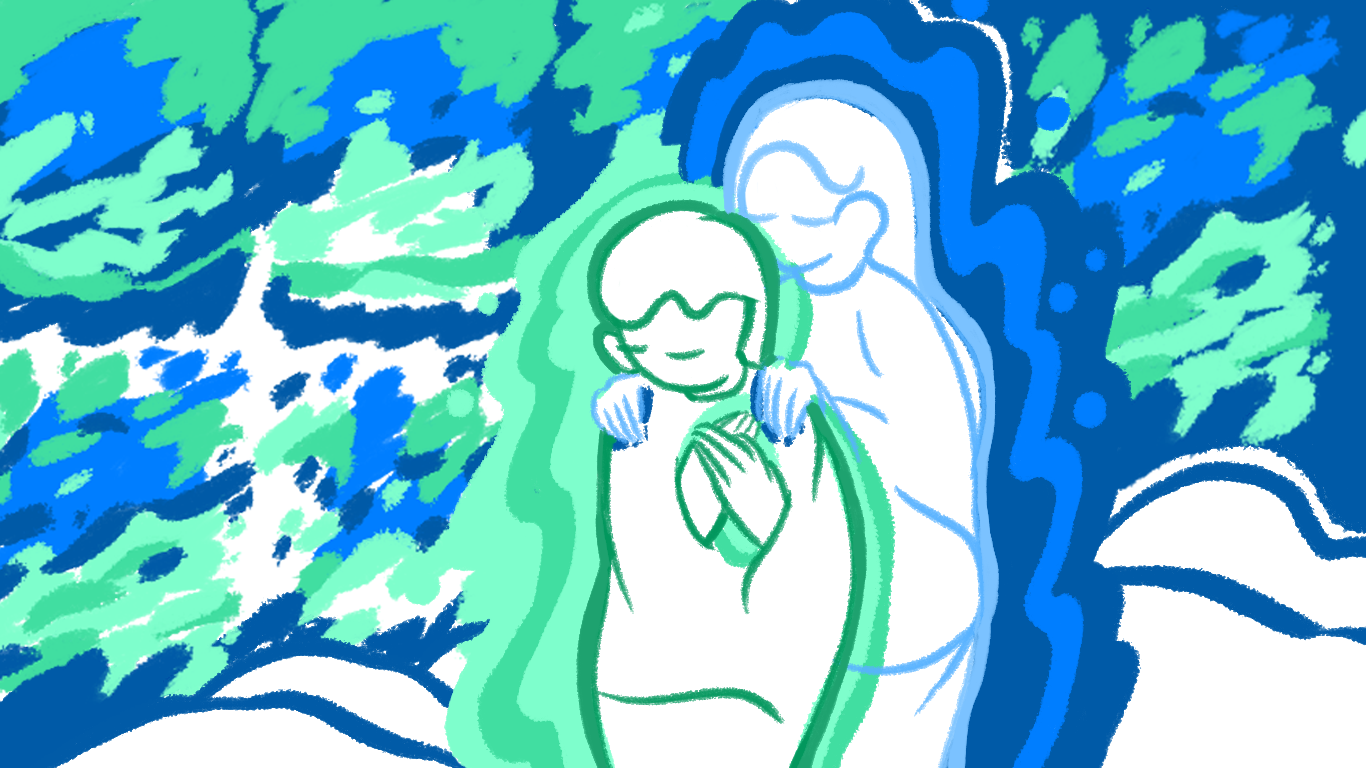

In early 2018, Argentina — home of Pope Francis — began a project to legalize abortion. My trip to Cafe Tortoni was in June of 2018, days before the Chamber of Deputies voted on the bill. The streets were crowded with women dressed in green holding signs: “Aborto legal ya. Ni una menos”. In Argentina, pro-aborto supporters wear green and pro-vida supporters wear blue. I didn’t see any blue that day.

The women in green stood in clumps without space to march, so their gathering felt more like a long, disorganized line for food at a sporting event than a heated protest. A few shouted and hoisted their posters over their heads; most chatted and laughed with one another. I took my time weaving through the crowd toward Cafe Tortoni. One woman stood above the others on the curb, naked above the waist with green paint on her chest. No one stared at her.

When I finally reached the cafe, a man in a black tuxedo opened the door for me from inside. He smiled, said hello, then shook his head as if to apologize for the crowd outside. He led me through the cafe toward my friends. We walked through the dim yellow glow, under stained-glass skylights, past bronze bust sculptures and around marble countertop tables with red velvet chairs, where people spoke quietly over churros and chocolate. At the table, my friends were already eating. They had just missed the march and had no idea it was happening.

We returned outside to the crowd after we paid for our food. It was sunset and the protestors finally had space to march and chant. Their green face paint glowed under the purple sky. We walked beside them. One group marched with drums down the street so no cars could enter.

After dinner that night, Maria asked if I had seen the pro-aborto march. I walked through it, I told her. She shook her head.

“It’s terrible,” she said. “It’s murder.”

I was quiet for a second. I sat on the white couch behind the glass table, facing Maria’s chair. I looked over to my backpack, making sure my green pro-aborto bandana was safely hidden inside. I’ve always been pro-choice. It’s easier in English, as the label more broadly describes a woman’s right to control her own body. The Spanish label “pro-aborto” sounds more grounded in the act of abortion than the greater feminist cause, though we’re all fighting for the same rights.

“It means murdering a baby,” Maria said.

“I know that some religions…” I paused, searching for the words in Spanish.

“I’m not religious,” Maria said. “It’s not about that.”

“Oh,” I said. “But in cases of … rape…”

“Those cases are horrible,” she said. “But they’re not the baby’s fault.”

“But in cases where the mother might die?”

“Try to save them both,” Maria said. She smiled, and said she’d show me a book about the value of prenatal life.

After Maria went to sleep, I sat on my bed and cried for a few minutes. I knew she’d worked for a conservative newspaper; I wasn’t surprised by her views on abortion. Still, it was more difficult than expected to sit through the conversation. Maria associated abortion with murder, or “matar.” Something about how Maria grew up, who she spent time with and what she read regularly, led her to see a certain cruelty in legalizing abortion. I didn’t tell her I supported the legalization of what she called murder. I didn’t have the Spanish vocabulary to eloquently discuss my views. It was frustrating to stay quiet, but I felt I should avoid upsetting Maria as her guest, just as I tried not to lose affection for her. We lived alone together. We still had a few weeks ahead of us. I kept eating the chicken she cooked and hiding my green pro-aborto bandana in my backpack.

That Wednesday, the abortion bill narrowly passed in the Chamber of Deputies, the final step before the Senate’s vote. Maria and I didn’t discuss the result.

The following Sunday, I turned 19. I spent the afternoon walking through Recoleta’s famous cemetery, partly because I liked the idea of visiting a site devoted to death on a birthday. It sounded like something a book character might do. Maria had recommended I visit. I walked slowly down the labyrinthine brick paths, between marble mausoleums. The tributes formed an eclectic collection of monuments from little Gothic chapels to Greek temples. Carved stone angels hovered above me, tacked on the roofs of high structures. I peered through low-wrought iron gates, looking down at tombs inside. The cemetery is usually crowded with tourists, but it was mostly empty that afternoon, except for the stray cats that gathered in its corners. Maria said to make sure to see Eva Perón’s grave. After Eva Perón died, her body was stolen and spent 20 years overseas before it was finally sent home to Buenos Aires. In the Recoleta Cemetery, she was buried almost 20 feet underground to deter potential kidnappers.

That evening, Maria said I could invite a few friends over for dinner. I invited three girls from class. Maria cooked us vegetable empanadas and asked my friends about their homes. When we finished eating, she carried out a chocolate cake she had baked herself, singing “Happy Birthday” in English. After my friends left, before saying goodnight, Maria handed me a gift in a pink bag: a delicate magenta scarf with yellow, blue and green flowers.

In August, after I returned home, I watched the Senate debate the abortion bill on livestream. Thousands of activists stood outside Argentina’s Congress for hours while the senators debated: green on one side and blue on the other. The Senate eventually rejected the bill 31-38. Today, though current President Alberto Fernández supports the right to choose, the COVID-19 pandemic has interfered with recent attempts to legalize abortion.

I haven’t talked to Maria in over two years now. She doesn’t like using technology, which she mentioned often, so I didn’t expect to keep in touch. For whatever reason, when I think of Maria and Recoleta. I think first of the silver scissor gate guarding her apartment’s elevator. I never thought much of that gate until the last time I pushed it aside, clutching my duffel bag against my chest, almost crying at the thought of never again struggling to move it. I miss Maria. I miss how she always said the word amusing in English when something made her laugh, instead of cómico or funny, and how she always threw her head back in laughter, with her top lip raised high in a smile. Whenever I see someone laugh like this now, I think of Maria and try to make them laugh again.