Claire Mutchnik

Ink runs from the corners of my mouth.

There is no happiness like mine.

I have been eating poetry.

— Mark Strand, “Eating Poetry”

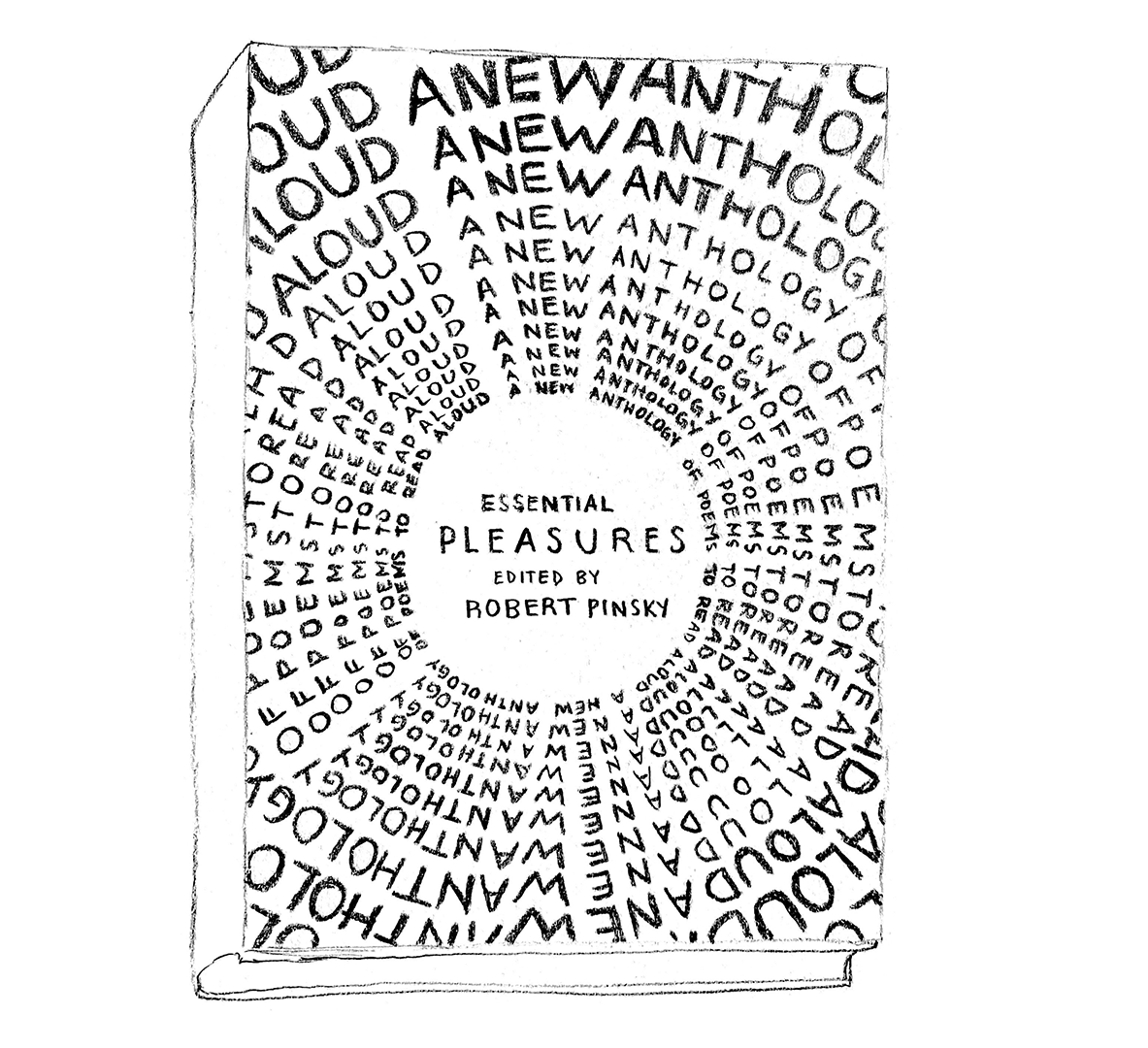

“Essential Pleasures,” edited by Robert Pinsky, is a 500-page collection of words that sound good. Pinsky challenges us to engage our aural appetites; he is there, as he writes in his introduction, to help us find the pleasure in “an organism of vowels and consonants and cadences flirting with an organism of meanings, playing with it, agreeing with it, arguing with it, converging, departing, twisting, energizing, goofing, weeping, punctuating, ironizing” — to help us understand the essential pleasures of poetry.

Seven form or genre headings divide the 285 poems: “Short Lines, Frequent Rhymes” or “Ballads, Repetitions, Refrains” or “Parodies, Ripostes, Jokes, and Insults” and so on. The order of the poems themselves reveal no recognizable pattern. The book gives us nothing but the poets’ name and their birth and death years, an informal presentation celebrating “the variety and depth of poetry.” Under “Love Poems” you will find Andrew Marvell (1621-1678) before James McMichael (b. 1939), and after a four-page layout of T.S Eliot’s (1888-1965) “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” comes the short and sweet “Days” by Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882).

Some poems you know. Some poems you read in high school English class: “Five years have past; five summers, with the length / Of five long winters!” and you realize five years have passed since you last read that poem. Some poems are new. You repeat the lines to yourself over and over: “We real cool. We / Left school. We / Lurk late. We / Strike straight. We/ Sing sin. We/ Thin gin. We/Jazz June. We/Die soon.”

I have spent exactly 92 days in a newly rented Howe Street apartment. Like many Yale students, I have been struggling to find a sense of home. Having booked an emergency ticket back from my study abroad in England, I returned to a foreign New Haven — few cars, closed shops and no students jostling to class. I decided to take the year off, partly because I couldn’t imagine sitting through hours of online lectures but mostly because my day-to-day misgivings about the security of my future suddenly lay bare, stripped of their Ivy League pretensions about one’s ability to be hired upon graduation. The fig branches of hope and opportunity that dangled with fruit over my head had collapsed. Wilted and died. I grew restless with the creeping dread that all things had come to a halt.

The pandemic sucks. You know it sucks. We all know the feeling of that impenetrable insomniac stress lurking in our subconscious, and we worry about how to reassure our parents that “Yes, I am washing my hands. No, I am not going out.” We tally the hours we can clock on student employment and feel sexually frustrated, because how do you satiate lust in the age of a pandemic? Lying awake late at night, it suddenly occurred to me: “Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player / That struts and frets his hour upon the stage / And then is heard no more.”

“Essential Pleasures” reminded me why I fell in love with poetry and taught me how to reconfigure my relationship to verse.

When you walk into the foundational courses for the English major at Yale, your professor will sit you down in front of Milton. You will spend many weeks slogging through “Paradise Lost” — the creation, the apple, the pandemonium — and then your professor will say, “Choose one passage. Copy-paste it into a new document. Stare at it. Stare at it hard, until something innate in the way that line breaks calls out to you, the way the couplet rhymes, the way the meter falters. Notice it. Wear your best blinders. Trot on like a diligent horse.”

There is something so familiar about the Yale English major slaving away at a line of Milton. The term “close reading” is ubiquitous across the humanities, and the image of a young scholar enraptured by a text feels enticingly democratic to us. Any undergrad, the theory goes, can and will spit out a cogent five-page paper about Eve’s fall in “Paradise Lost.”

Close reading, the all-American adaptation of I.A. Richards’ practical criticism, was born out of a movement to find an organized, critical method of analyzing literature. It was created as a tool, not in service of some final aesthetic value to be determined by, as some might call them, the “dead white men” of yore, but for the students of poetry — for you and me — to uncover our own meaning through poems: to learn, to grow and, I would argue, to find solace through tribulations.

While we are busy fretting about how to convince ourselves whether a poem is worth our time, we miss what Milton meant in his quandaries with good and bad, what he felt “On Having Arrived at the Age of Twenty-Three,” experiences that can feel so profound and enriching that it make us feel so seen. (Milton too felt insecure about his prepubescent appearance with the blasé coolness of youth! Milton sees you!) When we fail to feel the essential pleasures of poetry, we miss the point entirely and bore through the message that can uplift us from our fears and quiet our innermost anxieties.

In his introduction to “Essential Pleasures,” Pinsky writes, “Analysis and understanding can heighten appreciation. Sometimes, however, they obtrude: trying to force knowledge before pleasure has a chance. Pointing this out is not sentimental or anti-intellectual; on the contrary, the goal should be to encourage intellectual precision by putting it in a stringent, fitting relation to the actual experience of the poem.”

The actual experience of “Essential Pleasures” is full of hidden revelations.

“Choose a number from one to 489,” I say to my friends. Those are the pages in the anthology. The poem on the page reveals a secret only the book can tell.

In these few short months of possession, “Essential Pleasures” has hauled me through a quarantine breakup. It has carried me through the lulls of passing days with nothing to do but stare blankly at my computer screen. Poetry transcends the years printed under poets’ names, resonates with us deep in our bones and speaks to our present moment.

What Langston Hughes can teach us about the cultural identity of the Black American in “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”; the way an asterisk at the bottom of the poem redirects you to Carl Phillips’ “The Hustler Speaks of Places”; how to yearn for a long-lost lover many years after separation in Robert Hass’ “Then Time” — these are a few of the things I’ve been pondering during my time in lockdown. I cry. I pace about the room. I read the news. I watch endless episodes of the “Gilmore Girls.” I look outside to see the empty streets. These are the beats of our actual experiences, and more often than not, they feel sad. They feel laden with a certain heaviness that we are too young to know. Flipping through the pages of “Essential Pleasures,” I travel through time to gain the wisdom of my elders. I gather the strength to send myself to bed. I wake up the next day and remind myself:

This is the time to be slow

Lie low to the wall

Until the bitter weather passes

Try, as best you can, not to let

The wire brush of doubt

Scrape from your heart

All sense of yourself

And your hesitant light.

If you remain generous,

Time will come good;

And you will find your feet

Again on the fresh pastures of promise,

Where the air will be kind

And blushed with beginning.

— John O’Donohue, “This is the time to be slow”

Kyung Mi Lee | kyungmi.lee@yale.edu