Valeria Navarrete

I don’t think I’m voicing an unpopular opinion when I say, to put it lightly, this pandemic sucks. We’re cut off and isolated, we’ve forbidden (for good reason) large public celebrations or conventions, and those who have caught the coronavirus or are close to someone who has must now reckon with death or symptoms that may not fade for months. International relations are fraying in many parts of the globe, and domestic politics haven’t exactly improved either. Many students, not just Yale sophomores, can’t return to campus for class. Even Yale students on campus can’t have in-person classes. This is a historic moment, in the tragic sense. It’s very easy to be afraid now.

The human world is going through a serious struggle, but what of the animal world? I find myself reading portents in the foreboding changes I see in the lives of the animals in my neighborhood. I can’t believe how much has shifted in my absence. There is an old dog that lives in my neighborhood. When I was young, I’d walk in front of the porch he guarded, and he’d jump up and down and bark at me playfully. I grew older, and I stopped walking and started doing my homework. Now, with time and nothing to do but spend it, I walk past that same porch to find that dog too tired to even notice me. He lies, unmoving, his fur thin and gray. He’s grown weak.

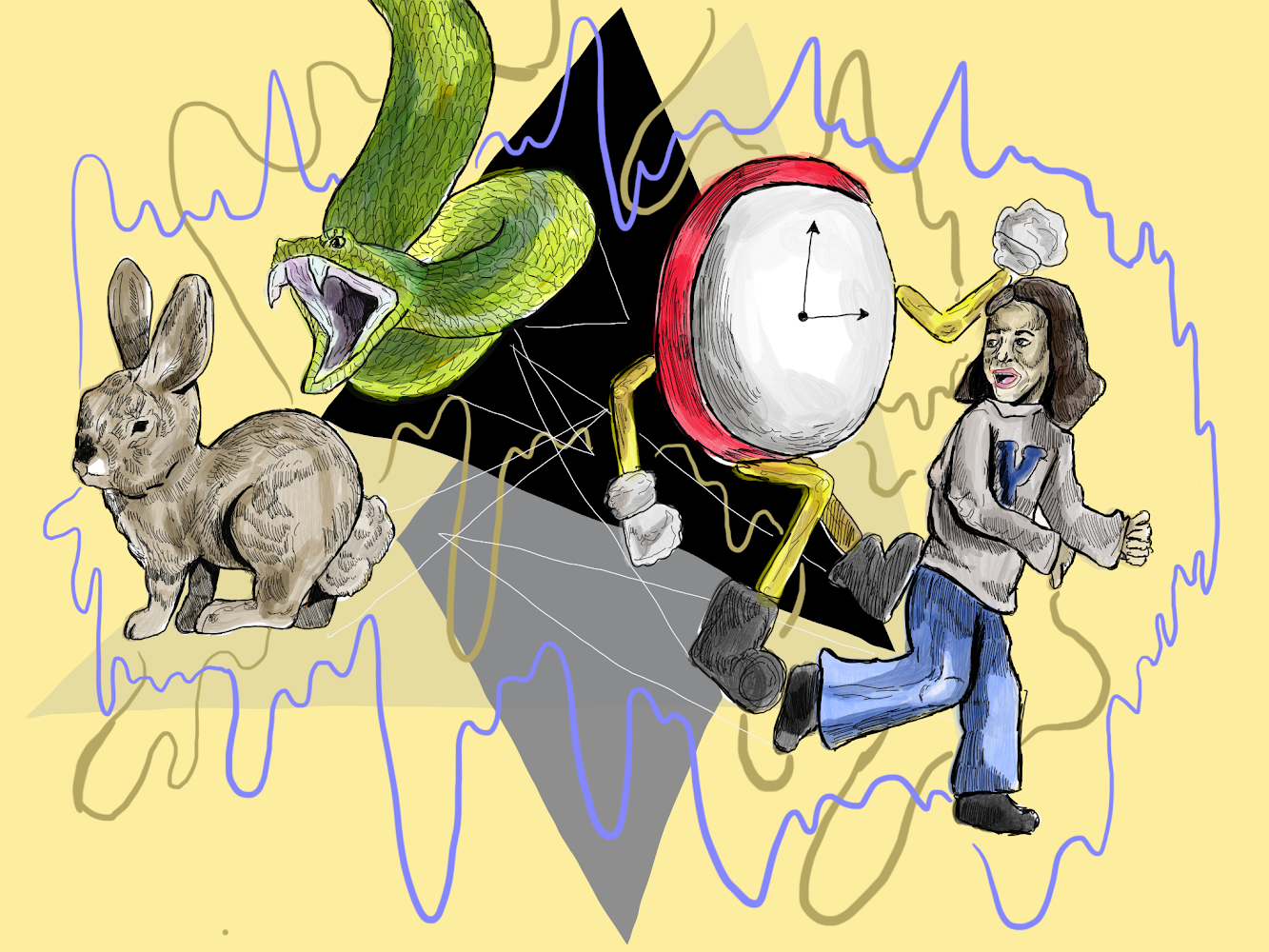

I’ve grown weak too; my mother comments on how I’ve been slouching much more often in recent months, and I find my muscles going lax. And the snakes have come closer. My mother would always warn me of the holes in the ground — snake holes. I saw snake roadkill once; the snake was huge, easily the length of a small toddler and a half. Taiwan, where I’ve been living for the past 10 or so years excluding my time at Yale, has some harmless species, but just a few months ago in May, I stumbled upon a banded krait (the species with the deadliest neurotoxin) right outside my door. At first, I thought it was just a rope; it was very possible I could have stepped on it without realizing. If I had, I would’ve had to go to the hospital immediately, and potentially would have died within the day.

And whatever happened to the rabbits? Where are the fluffy little things? I wonder about those rabbits. They’re not native to this climate at all. We used to put out bowls of lettuce for them, on the sidewalks, so they could eat at their leisure. We cared for them, we wanted them to live, despite all odds: nature, their natural predators like the snakes, the inclement weather. If we cared for the rabbits so much, why didn’t we take them inside? Why didn’t we keep them safe? One by the one, the rabbits died. By the time I returned in March, there wasn’t a single rabbit left. They were eaten by snakes.

Was their purpose merely aesthetic? Were we expected not to feel sad when they disappeared? I wonder if they ever, even on some small level, realized they were cared for just enough to be given food, but not enough to be given the same consideration we give to lab rats, safe and snug in their cages.

In early summer, I couldn’t help but indulge in a bit of homegrown superstition — like the ancient Greeks, I saw the lives of the animals as somehow reflecting my own. It’s natural for humans to look for meaning in the midst of a scary and chaotic world — to look for a sign, a message. So, with the snakes at my door and the cats screaming under my window at 4 a.m., I nurtured the toxic idea that I was in peril, that I was facing impending doom. Intellectually, I knew I should have expected a close snake encounter at some point, and that dogs do grow very old at age 14 — but still I interpreted everything as an omen about how I would never return to Yale, or fail in my studies, or grow disconnected from all my friends. This wasn’t an intellectual belief; it was an emotional one.

Some people derive comfort from action. I didn’t want to fall into an irrational nihilistic despair over the deaths of seven bunnies, so I turned to hyperproductivity to cope. Growing up in a capitalistic society, there is the idea that every scrap of time must be used — not for leisure, but for developing one’s own human capital. Every interest, every hobby, can and should be monetized; or, at least, you should try to make it a Yale club for funding and prestige. If I’m not baking bread or starting a podcast or at least finishing my watchlist during this quarantine, then what am I doing?

Perhaps predictably, I burnt out very quickly from trying “I’ll read three books a day while having a part-time job and summer classes” hyperproductivity. Humans can’t push themselves that far; we’re still bound by our need for sleep, our need for companionship, our need for entertainment. So if we cannot be hyperproductive, perhaps we need to use this time for personal change? We can shed our skins like the snake and use this extra time for metamorphosis, a self-contained evolution. Time must be used, after all. It can’t just sit there. If you don’t occupy it with some positive action, at least fill it with positive thought! Emerge from the pandemic with a shiny new self to show off, with some of those personality traits you’ve always craved, and maybe even a bold and daring set of opinions.

Or, perhaps, we can acknowledge that it’s all right to take some time to take care of yourself. We don’t have to shove aside our feelings about how dark and dangerous these current times are. We don’t have to treat the coronavirus pandemic, a global tragedy, as another opportunity to utilize time for some utilitarian purpose — an opportunity we have to punish ourselves for wasting if we don’t use it fully. Yes, reading omens in the behavior of animals has been an obsolete practice for at least centuries, but it’s equally unproductive to ignore the emotions that inspire such practices. Humans don’t expect animals to have to constantly be justifying their worth to exist through productivity or self-improvement. No one asked the dog to stop aging, or even the snake to stop biting. Humans, as ostensibly “higher” beings, should have even more of a right to just exist — to relax and maintain personal, emotional health in the middle of the greatest pandemic for a century.

Claire Fang | claire.fang@yale.edu