Survey shows first years support social movements

Throughout the summer, incoming Yalies marched.

One of those marchers was Ruhi Khan ’24, who demonstrated in May to support Black Lives Matter in her predominantly white hometown of Newark, Delaware. The march was peaceful, she said, and she was “moved” to see that many non-Black people like her — Khan is Indian — had come out in solidarity with the movement. During that procession, one of the onlooking police officers asked to take the microphone, Khan said, and in front of the crowd, he asked if attendees could keep it peaceful and safe; his daughter was marching.

Activism was a major topic of this year’s first-year survey, which was sent out by the News to learn more about the incoming Class of 2024. In March, Yale announced that it had admitted 2,304 students to the newest class of Yalies. But due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 341 students elected to take gap years as of Sept. 1, up from just 51 in the previous cycle. The anonymous survey — which was sent to 1,207 matriculating members of the Class of 2024 and accepted submissions between Aug. 31 and Sept. 2 — received 471 responses, for a response rate of 39 percent.

While the 471 students who responded to the survey answered questions about their residential colleges and their thoughts on Yale’s plan for the pandemic, many students also shared their opinion on politics.

Khan was not the only first-year student to march. Others in her class also took to the streets and to social media to stand against police brutality. And while several first years interviewed by the News have differing opinions on the numerous movements that made headlines over the summer — and continue to do so — one thing is clear: many members of the newest batch of Yalies, from Delaware to Utah to California, consider political and social activism to be a core concern.

ACTIVISM AT HOME

In Corpus Christi, Cynthia Sutanto ’24 attended two “strictly non-violent” Black Lives Matter rallies that focused on spreading awareness of police brutality. Additionally, the events provided a platform for Black artists to share their thoughts on the movement, Sutanto wrote in an email to the News.

“I chose to be a part of these rallies to stand in solidarity with members in my community who are affected by police brutality,” Sutanto wrote. “I believe these events are an important way to inform the general populace about racial inequality. The large amount of media attention that rallies/protests gained put pressure on lawmakers to make a change.”

Still, Sutanto noted that she perceives much of the current activism as performative, and hopes that activists will go beyond social media and into politics to advocate for change.

Jamarc Simon ’24 told the News that he “100 percent support[s] the Black Lives Matter movement,” saying that the country is moving in the right direction. While Simon added that he is “a little iffy” about the Defund the Police movement, he said that he supports better training for police officers and fully supports protests against police brutality.

From the survey results, most students have similar feelings.

Nearly three-quarters of first years who responded to the News’ survey, or 74 percent, were “very supportive” of the Black Lives Matter movement, while 17 percent were “somewhat supportive.” Respondents answered similarly when asked whether or not they supported protests against police brutality.

But distributions differed when students were asked if they supported the Defund the Police movement: just 34 percent were “very supportive,” while 11 percent and 12 percent of respondents were “somewhat unsupportive” and “not at all supportive,” respectively.

25.3 percent of first years who answered the survey said they had participated in a protest against police brutality this summer, and 49.9 percent said they weren’t able to attend a protest, “but wanted to.”

Even though Matthew Miller ’24 was not able to go to any protests for very long because he has family members who are at high risk for COVID-19, he told the News that he does wholeheartedly support Black Lives Matter and defunding the police.

“I do feel very strongly about the matter, being Black, so I want to be a part of the change,” Miller wrote in an email to the News. “The idea of defunding police was new to me but it makes so much sense — I’m also a very big mental health awareness advocate and often police do not properly respond to delicate mental health crises.”

Other students told the News about how sentiment for police reform has made its way past the sidewalks and streets and into their homes. For the first time, Mahesh Agarwal ’24’s immigrant parents are considering anti-Black racism, and Agarwal himself has learned about “nitty gritty issues” such as broken-windows policing.

For Agarwal, critically examining law enforcement is a crucial method of reform.

“I love that we’re questioning a core aspect of society,” Agarwal wrote to the News. “Does our criminal justice system need to look exactly the way it does now or could we imagine a more effective system? I don’t like the idea of pitting people against each other or burning everything down. I see issues through a policy lens rather than an ideological one.”

Gabe Ransom ’24 told the News that while he already cheered on movements to reform the police, the shooting last week of a teenager with autism near his home in Utah brought the issue closer to home.

“It was especially powerful for it to happen right next to my house, because most of the incidents that everyone talks about are Atlanta, Minneapolis, Ferguson, places that are not close to me,” Ransom said. “It always sets in a little bit more when it’s your community.”

Students protest the Yale Police Department following the shooting of Stephanie Washington and Paul Witherspoon in April 2019 (Ann Hui Ching)

POLITICAL LEANINGS

Similar to past years, the incoming class skews heavily liberal, with 32 percent and 46 percent of respondents saying that they were “very liberal” and “somewhat liberal,” respectively. Very few students identify on the other side of the political spectrum, with just 7.9 percent and 1.3 percent of respondents calling themselves “somewhat conservative” or “very conservative,” respectively.

Opinions on social acceptance based on political leanings also varied. A far greater proportion of liberal-leaning respondents answered “yes” when asked if they thought their political views would be accepted on campus, whereas the majority of conservative-leaning students answered either “no” or “unsure.”

These results line up with Suanto’s impression of the political landscape among first-year Yalies, based on the interactions she’s had during her first two weeks on campus. While most of her peers lean left, she said, she has also made friends with students whose views lean centrist or right. And while her left-leaning peers tend to be very vocal about their beliefs, the more center- or right-leaning students have been less so.

“These students tend to not broadcast their opinions because they fear being ‘canceled’ by other Yalies,” Sutanto wrote. “I believe this trend is problematic because it stifles the potential for productive political discourse. In order to actually change the minds of students (who are ultimately the future of this country), there needs to be a willingness to and acceptance of listening to a wide range of opinions.”

For Simon, Yale’s political environment is a welcome change — his high school community, he said, did not generally hold the views that he does. The “good thing” about Yale, Simon said, is that it seems like a safe space to voice one’s opinion, and he does not think that “people will condemn you for your political views.” Still, he said that he is biased in this particular case, because the overall campus political tone matches his own.

Han Choi ’24 shared a view similar to Sutanto and Simon.

“I think we can all agree that the Yale student body is definitely super liberal and left-leaning,” Choi said. “To me and to other students … just meeting people in my res college, I’m starting to see that there’s a lot more people with differing views, like not that far to the left, but I actually think that most people would be accepting of views even on the other end of the political spectrum.”

EVEN WITH ONLINE CLASSES, STUDENTS COMMIT TO ACTIVISM

Before Choi came to Yale, he joined a police reform advocacy group in his hometown of South Pasadena near Los Angeles. While his local police department did not grapple heavily with the issues criticized within the Los Angeles Police Department, Choi said, he and his group looked into the police handbook and looked for ways to increase transparency and accountability.

Even though Choi’s activism took place in his hometown, survey results indicate that almost half of first-year students — 46 percent — plan to engage in activism while at Yale. And while 36 percent of students are unsure of their plans, only about 18 percent said that their time at Yale will not include activism.

Multiple students interviewed by the News said that while activism at Yale did not play a major role in their decisions to matriculate, they appreciate what they perceive as the University’s broader culture of advocacy. For Sutanto, her interests lay in the Yale Undergraduate Prison Project and the Yale Prison Education Initiative, both projects run through Dwight Hall and both address issues she cares about.

“While activism did not specifically influence my decision to come to Yale, I did love the sense of community that Yale has,” Sutanto wrote. “Yalies are almost always willing to go the extra mile to support one another and their New Haven community. In the face of great racial inequality and a pandemic, Yale students make a point to not be complicit.”

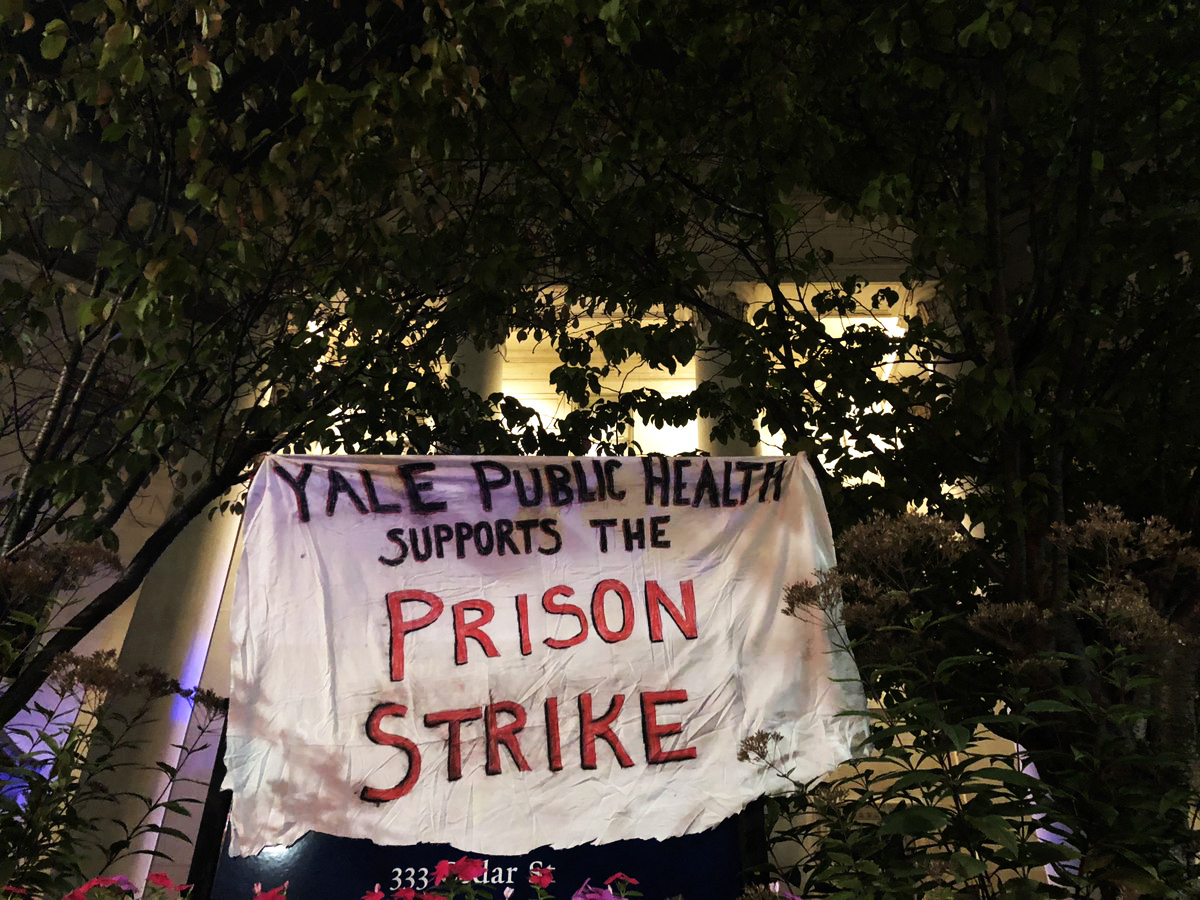

Yale students express support for prison abolition in 2018 (Courtesy of Eli Feasley)

Miller echoed Sutanta, saying that student activism and the general passion for social movements has influenced him. While activism will not be his main focus while at Yale, Miller said, there remain issues that he wishes to fight for.

“I do plan to participate in political activism, much to the chagrin of my mother who told me that when I get to school, I just need to ‘keep [my] head down and do [my] work,’” Miller wrote. “I don’t think I would have ever considered myself an activist until I saw the change other Yalies were trying to create and realizing I could participate as well.”

Students from the Class of 2024 come from all 50 states, in addition to Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico, and 72 countries.