Adrian Kuleza, Staff Photographer

At a June 4 rally, New Haveners called on the city to cut this year’s police budget by $33 million — over 75 percent. A coalition of anti-police brutality groups on June 15 demanded that Mayor Justin Elicker make a discretionary $2 million cut to the alder-approved police budget — effectively negating the $1.6 million increase from 2019 to 2020 — while moving towards full abolition.

In the Elm City and beyond, people outraged by continued police violence against Black communities argue that the solution lies not in reform, but rather in divesting from policing and investing in social services.

Elicker sent an email to city residents on June 8 expressing his support of activists’ long-term vision and his openness to continued conversations about the role of law enforcement. Still, he maintained that New Haven’s police force — which he said answers over 100,000 calls each year — is not going away.

“We must strive for a time when we won’t need police, and to do so we must invest in a social safety and support net that addresses the roots of the problem, not the symptoms,” Elicker said. “I believe in this vision. [But] I can’t support outright defunding of the police.”

Where does the money go?

The New Haven Police Department’s budget has increased in recent years at about the same rate as the city’s general fund. Over the past five years, the department’s allocation has grown from $37.4 million to $43.1 million, with a slight drop between 2018 and 2019. The largest spikes during that time frame include a $3.6 million increase from 2016 to 2017 and a $1.6 million increase for the upcoming fiscal year.

The vast majority of NHPD spending — $32.9 million, or 76.3 percent — goes toward salaries, most of which cover the city’s 340 patrol officers.

The next largest share of spending is slated for overtime payments, totaling $7 million. Supplies, equipment and other material allowances make up the remaining $3.2 million.

Those figures do not account for police benefits, such as pensions and healthcare. Over the past 10 years, police pensions have run at a rate of 41.4 to 52.1 percent of officers’ salaries, meaning that total police expenditures are significantly higher than the departmental budget. In this year’s budget, police and fire pensions clock in at $39,595,014 — the fifth highest general fund line item.

Still, this figure is lower than it could have been. Last summer, the city and police union negotiated a delay in officers’ pension eligibility that would have saved the city $20 million over the previous five years had the rule been in effect, Chief Administrative Officer Sean Matteson told the New Haven Independent.

Other contractual changes to pension expenditures include an increase in employee contributions and a decrease in cost of living adjustments — changes in benefits to counteract inflation — both of which drive down city obligations. The increase in pension spending this year is relatively low compared to recent years, some of which saw significant jumps.

What changed in this year’s budget?

The Board of Alders approved a budget in May that cuts the total number of police department positions from 494 to 463, in line with Elicker’s March proposal. The mayor’s original pitch cut 80 vacant positions across the board to help close the city’s $45 million deficit while maintaining base funding levels for social services.

The NHPD felt those cuts more than any other Elm City department. Most cuts — 28 of a total 31 positions — affect sworn positions, which include patrol officers, detectives, sergeants and others.

But a reduction in budgeted positions does not mean a reduction in the overall size of the active force. Rather, given a large number of vacancies, the NHPD still has room to grow and intends to do so, city officials emphasized when announcing the budget.

“It’s important to note that, while we reduced the overall number of funded positions in the Police Department, our team left enough funded positions to ensure that we can bring in new officers this year to help rebuild the size of our depleted force,” Elicker said in his March proposal.

Black Lives Matter New Haven demanded in a June 15 Facebook post endorsed by other activist groups that the city’s police force stop all hiring immediately.

According to April’s monthly budget report, the NHPD currently employs 340 sworn officers — nine of whom are stationed at schools — meaning that the department could grow by nearly 20 percent to reach the upcoming fiscal year’s capacity of 406 sworn officers, reduced from a previous 434.

That reduction — less than a third of the total number of vacancies — generated $3.5 million in savings. The city is currently slated to fund 66 positions that it had not filled as of April’s monthly report.

New Haven has struggled with police retention in recent years, especially since 2016, when an existing police union contract expired. The department lost around 100 officers over the next three years, many of whom retired and others of whom sought jobs with neighboring departments, such as Yale’s and Hamden’s.

Both of those forces offer better benefits and starting salaries of about $76,000 — the top of Connecticut’s range. New Haven is at the bottom, with a base payment of $49,387 this year.

That’s about $5,000 more than what new officers earned three years ago. The increase comes from last summer’s contract negotiations, in which the police union secured a 13.5 percent salary increase over six years, which retroactively include 2016 through 2019 and extend through 2022. The union also won 8.5 percent in retroactive pay, which appears as a lump sum in each subsequent budget.

Pay raises are estimated to add a cumulative $10 million to the police budget over the contract’s lifetime.

This year’s budget also includes a $1.3 million increase in overtime payments, reflecting a higher compensation rate as well as 100 percent retroactive pay for overtime worked before the most recent contract passed.

The chief also got a raise this year. His salary — now $169,900 — is at the top of New Haven’s permitted range and above that of chiefs in comparable Connecticut cities.

The Civilian Review Board, a police accountability body established in 2018 after decades of activism, maintained the same allocation as last year: $150,000, or three times what the CRB got the year of its founding. The money does not come from the NHPD’s budget.

How does New Haven’s police spending compare to other city expenditures — and police expenditures in other cities?

Police services are the city’s fourth-largest general fund expenditure, following education, medical benefits and debt service, in that order.

The city’s general fund allocates about 4.3 times more to police services than to human services, which include disability services, elderly services, the fair rent commission, public health, the youth and recreation department and the community services administration. The administration splits its $2.5 million budget — cut from $2.9 million last year — about evenly between administrative costs and housing for the homeless.

While the police budget increased by $1.6 million this year, social services funding stayed stagnant across the board. The Board of Education received another $1 million, which is less than a third of the $3.5 million increase Elicker originally proposed. The mayor’s proposed increase itself was just around a third of the $10.8 million that the embattled board said it needed just to keep the lights on.

Public schools get a significant portion of their funding from the state, but Connecticut’s money is drying up and New Haven’s grant has flatlined recently even as local costs increase.

Here is a breakdown of services supported through the general fund:

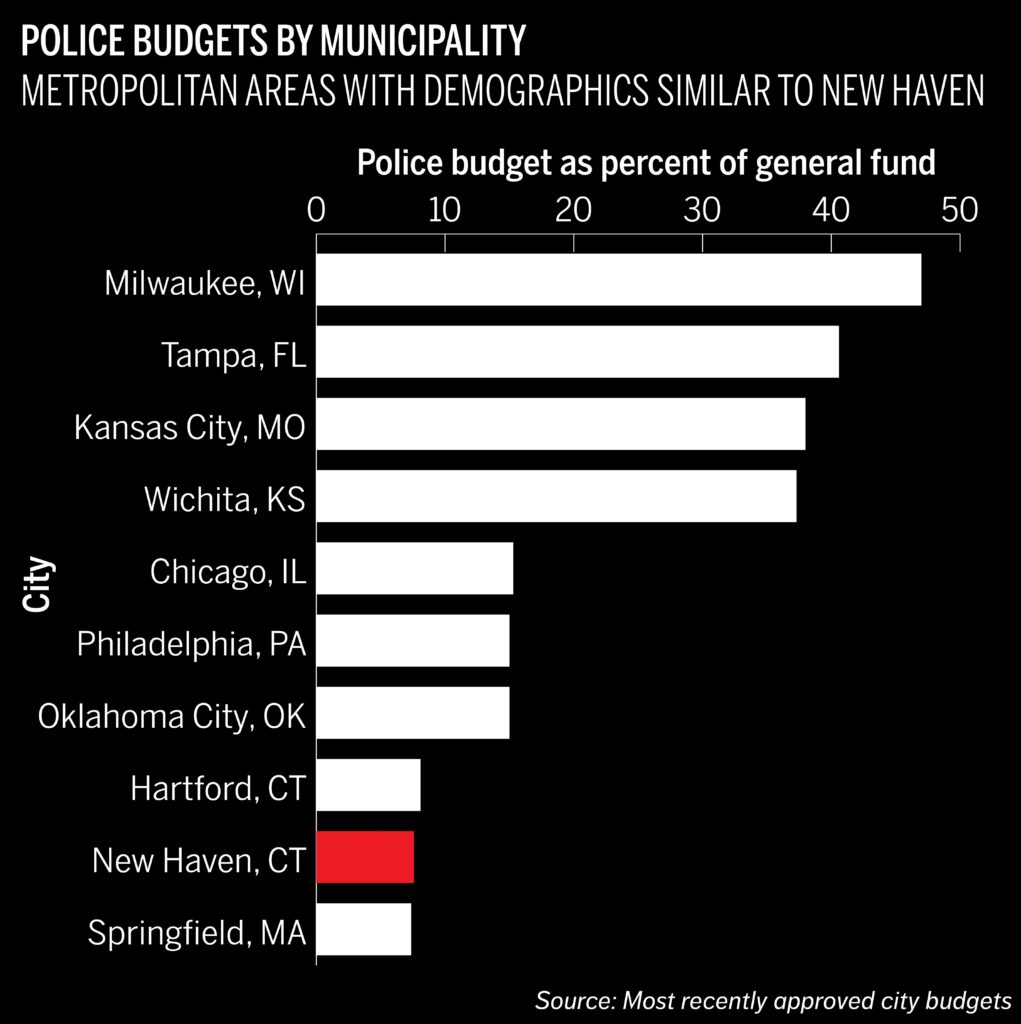

Some police departments — like Los Angeles’ — have budgets that comprise more than half of their cities’ general funds. New Haven’s allocation is much lower, hovering between 7.15 and 7.61 percent of the general fund in the years since 2016. This upcoming fiscal year, policing will account for 7.59 percent of Elm City expenditures.

Here is how that figure stacks up against 10 other metropolitan areas with similar demographic profiles:

Mackenzie Hawkins | mackenzie.hawkins@yale.edu