Victor Serapiglia Cioffi

2019 was the year that I lost myself in an avalanche of intimacy. I didn’t know a heart was capable of expanding so much, of displacing ribs and lungs as it inflated, of taking up so much space that my breath caught in my throat and my chest ached with joys previously unknown. The feeling of falling in love is such a terrifyingly beautiful experience because it is quite literally “falling” — your heart is radiating with so much warmth that you feel astral, a celestial body hurtling, falling through space as it is bursting with joy. It is a feeling of losing control, of giving yourself wholly to another, of cracking open at the core like Dora Maar in a cubist painting to reveal all of your inner secrets and insecurities. You relish in your power, bask in your vulnerability, cherish being a muse fueling someone else’s desire. You levitate, and you recognize for a moment that love is that gravitational force that is keeping you in free fall, flying, holding your pieces suspended. 2019 was also the year when we fell apart — lost love always leaves a mark. ///

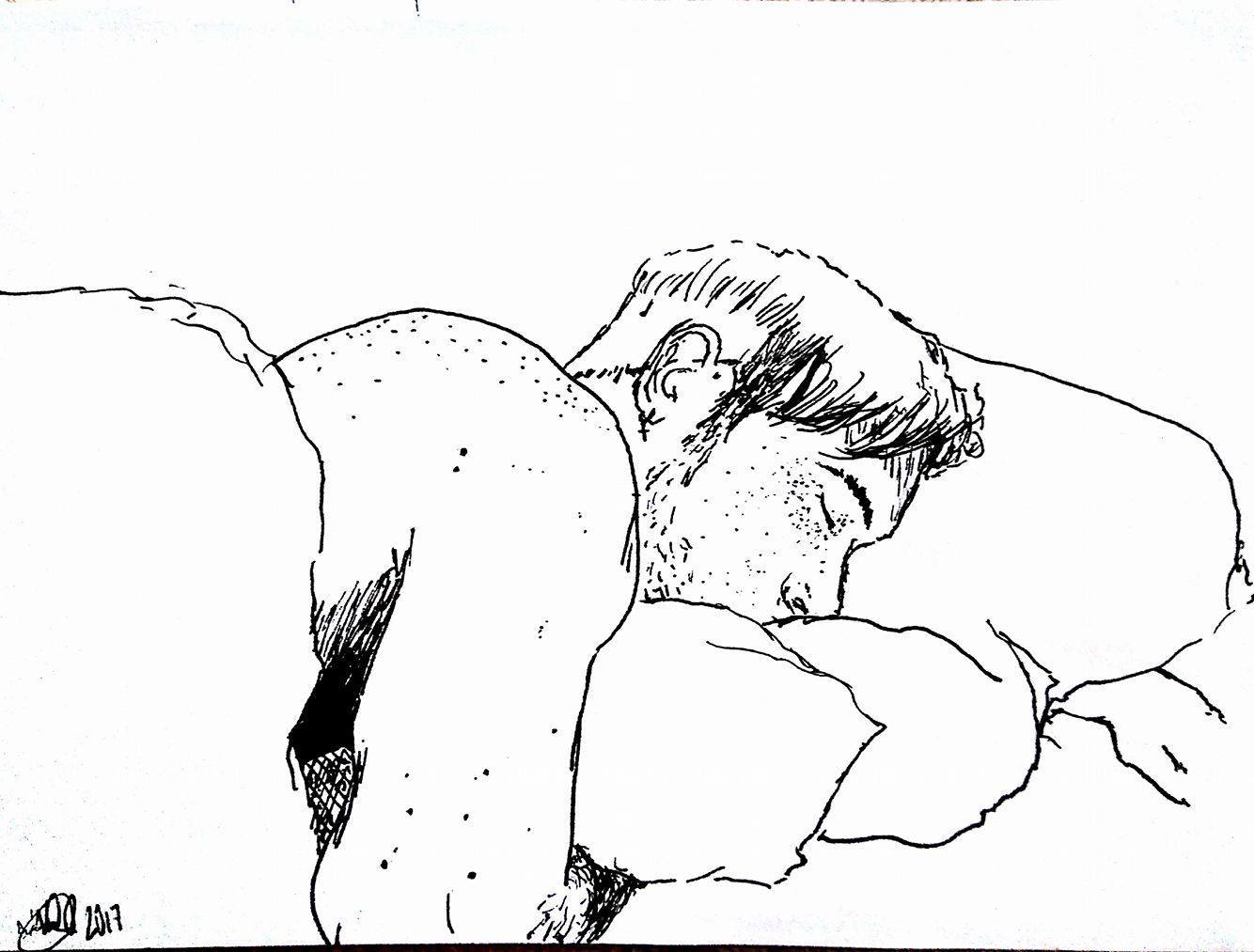

In April of last year, my heart contracted so forcefully that I was sure its rhythmic tambourine must have been audible in California reverberating off the gray bricks in New Haven, a seismic vibration, a sound that reminded me of my vitality and how necessary love is to being alive and connected to the rhythms of the earth, an earthquake that magnified the echoes of my desire buried deep in my soul and hidden in the recesses of my spine. My toes barely touched the ground in May as I folded myself in our quiet pretzel of an embrace, two celestial bodies that had the luck to gravitate together long enough to share an orbit. I finally understood what e.e. cummings meant when he wrote, “i want / no world(for beautiful you are my world,my true) / and it’s you are whatever a moon has always meant / and whatever a sun will always sing is you … this is the wonder that’s keeping the stars apart / i carry your heart(i carry it in my heart).” The weight of carrying another’s heart in yours is not burdensome, but beautiful; not heavy but light. It is not an assignment, but a privilege. Every date was a revelation of intimacy, every touch a million years of joy condensed in two clasped hands, stress and fears forgotten in a kiss, almost a year of museum visits and Korean fried chicken, of walking together in the rain and getting ice cream, of simple gifts and gentle joys, of waking up in each other’s arms, of laughter and losing track of time falling together at once. I remember the gray scarf you wore the night we met, our first kiss across from Rudy’s — do you remember that night? — the faint pine scent of your cologne that reminded me of forests, of making pizzas in your oven, the burrata cheese charred, stuck to the bottom of the pan. I wrote “I love you” in Hangul again and again, trying to copy the curled Korean script that would bring me closer to you, bring me closer to being understood, to understanding. “I love you, I love you, 사랑해.” ///

For a moment, I allowed myself to think, “This might be the one,” a thought that passed fleetingly but just long enough to give me a glimpse of a future that looked so inviting, so comfortable, filled with laughter and children, gallery openings, parades of memories not yet made, full of promise. Just a smile was enough to make my knees tremble — I would have built a ladder to the moon with seashells just to see that smile looking back at me every day. I would have lassoed the sun just to have you. Love is all-consuming. Love is foolish, violent sometimes. Love is the best thing to happen to any of us. ///

2019 was also the year that this relationship ended, unexpectedly and without warning; no cracks appeared before it ruptured. But perhaps the warning signs were there, perhaps I hadn’t noticed because I made excuses for all of the red flags: a forgotten date, unanswered texts, a coldness that I couldn’t quite place. He’d said he was depressed, busy — but only too busy for me. Once when we were walking I’d asked him if he was depressed about our relationship and he paused, sighing deeply. His silence said so much, and not enough. Little insecurities snowballed: We fought and he left, leaving everything unresolved. With its end, my heart imploded. A grenade splintered my chest into tiny pieces of shrapnel that I am still searching for beneath the couch cushions, sweeping up in the corners of the room, finding buried under piles of laundry. Some pieces I haven’t found yet, and some I think I might never find; but I have improvised. Just like kintsugi, the centuries-old art of repairing broken pottery with gold in Japan, I have begun reassembling my self-esteem and my broken heart piece by piece. Instead of with gold, I have been repairing my heart with hope for the future, filling it with other things that bring me joy. I bought myself flowers and used some of the petals to shore up the holes. I baked a cake and used some of the dough to smooth over the ridges of the open wound. I lit candles and poured the hot wax into the open grooves, letting it gently seep into the emptiness. I adopted an abandoned sock I found behind the dryer, thinking to myself that it probably felt just as orphaned and lonely as I did. It has been eight months, and still the holes remain. I will fill these holes completely someday, but I know the silhouette of the scar will always remain. I am comforted by this, knowing that while the soul will heal, lost love always leaves its mark. At least I am tattooed with a reminder of what was, of us. Loss is never forgotten, and while people might never move on, they certainly move forward. ///

Carousels of uncertainty cycle through my mind with all of the possible outcomes that could have caused things to go differently. Did I listen closely enough? Was I supportive enough? Did cultural differences get in the way? Why did you say those hurtful things and not apologize for them? Why didn’t you prioritize me more? Why did you ask for a break? Did I overreact? Sometimes I imagine myself in another dimension in which the plot had gone differently — where would we be now? More importantly, who would we be now? I still have so many questions left unanswered. I tried to apologize, to make things right. Love is the opposite of cowardice. It takes courage, intention. It takes grit and patience. Love is the most radical thing you can do. ///

September was a month that I remember only vaguely. I spent most of it in bed, skipped most of my classes, wore the same shirt for a week (a shirt that you wore once), wrote so many journal pages and used so many tissues to dry my eyes that I’m sure I was singularly responsible for deforesting a 10,000-acre swath of trees in the Peruvian Amazon. September was a month of hot showers and scalding broths, of shots of whiskey, of fried comfort foods dripping with grease, and anxiety meds. There is a permanent U-shaped imprint in the couch from how often I sat there, curled up, immobilized by grief, an indent like those made in Pompei after Vesuvius erupted and froze everything in ash, like the you-shaped imprint in my heart that still has not been filled. I went to church, then I stopped. I bought new clothes to disguise myself from myself. I took up odd hobbies: learning Portuguese, reading about breeding cats, looking up the capital cities of countries that I would never visit. I bought a piano and sent it back because the pedals stuck and made everything legato and sad. I read Anaïs Nin, Abdellah Taïa, Matthew Lopez, Eileen Myles. I joined a gamelan ensemble so that I could take time out of my week to wield a heavy wooden mallet, venting my stress by pounding out loud chaotic melodies that — at least for a moment — broke the serpentine, cyclical thoughts of grief and regret that consumed me. I took up running, trying to outrace my insecurities and my racing thoughts. ///

I cried in libraries, the back of taxis, in bathroom stalls, at movie theaters. I cried in parks in front of children on swings, at choir rehearsals as we sang about God, in front of therapists, into chai tea lattes. The wet trails I left behind formed streams that united me with rivers of the most basic human emotion: loss. I talked to strangers about my ex who nodded knowingly. “Do you know the American graphic designer David Reinfurt?” I would say. “No,” they’d say, uninterested. “I don’t either,” I’d say, telling them that I couldn’t make myself read about him because it reminded me too much of my ex, one of the most talented graphic designers I’d ever met. I deleted podcasts about design, removed photos of Chandigarh chairs from my wall, threw away a book of photographs of us you’d made me for my birthday — a monument of intimacy — but then quickly retrieved it because I couldn’t bear to part with it, tried not to think about things that made me think of us or that made me think at all. Thinking was the enemy of progress. Thinking was progress. But progress was grieving. And grieving was pain. ///

I cried when I saw people laughing, or hugging; I felt personally attacked seeing people kissing. “Get a life!” I’d think, bitter that it wasn’t us, but then ashamed that I’d thought something so angry about something so pure. I cried once when I saw a dog shitting because it was making a face that I’m sure looked just as vulnerable and desperate as I thought mine did, just as ashamed as the world watched, its legs shaking just like mine did when I saw my ex in public. I laughed, tears streaming down my face, realizing how pathetic it looked, and how pathetic I felt. I blamed myself. I blamed you. I blamed no one. I cried when I heard K-pop songs, or passed places we used to go out together to eat, when Facebook recommended mutual friends, when I went to the Whitney in New York because that’s what we would have done together if we had lasted. I thought of the trips we would have made to the Glass House and Fallingwater, the hikes in Vermont, all of the things I wanted to say but didn’t or couldn’t. I couldn’t walk past certain roads. And when I did, I walked quickly, pretending to talk on the phone; I tried to distract myself, but my eyes would invariably wander hungrily up the marble stairs to the place where I once waited outside the art school, the place where you once stood waiting for me. ///

I gained 10 pounds, then lost 5, then gained 10 more pounds. Then I stopped counting. I would wake up at 4:00 a.m. and think about the time I shoved half an orange in my mouth, juice dripping down my chin, just to make you laugh, or your gentle rising and falling breaths as you slept, or the gentle plucking of your guitar’s strings distorted by distance as you serenaded me over video call 10,000 miles away. Or the time we rented a villa in Bali and sat by the pool, listening to the cicadas and looking up at the stars. I cried in front of my roommate once because I forgot my ex’s favorite color. “How could I have forgotten?” I yelled as tears rolled down my cheeks, blaming myself for everything and anything, thinking that this one forgotten detail was responsible for the downfall of my world. You remembered mine: teal like the ocean, a color of violence and tranquility, a contradiction. My roommate offered me a tissue, holding me as I howled, his arms keeping me from spilling out entirely. Sometimes I stared at myself in the mirror and belted Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger,” roaring and clawing desperately in the air, taking pleasure in how ridiculous I was; other times I would just stand there staring at myself quietly, naked, telling myself that I was enough even when I wasn’t sure. Sometimes I would call friends just to listen to them eat, having nothing to say but enjoying the simple fact that although the hole in my chest that formerly held my heart was empty, at least their bellies were full. “Are those Cheetos?” I asked once, fascinated by the sound teeth made through those cheesy, crunchy clouds. But fullness of any sort made my emptiness seem all the more chasmic. Sometimes I talked about emptiness, too. Often I said the same things over and over again, cyclically, and tried to rationalize an ending that seemed to have taken place far too soon, that seemed impossible and unfair, an ending that was avoidable if we had only talked. I read through old texts, looked at old photos, then texted my ex, then tried to stop. Then texted again. Your silence told me everything I needed to know. But love is impulsive and irrational, and it is slow to forget. ///

There are places I can no longer go, concerts I can no longer attend, people I can no longer see, foods I can no longer eat. Not yet at least. Kimchi is one of the foods I can’t eat. It smells of the past, pungent. It smells of a past that I can no longer return to no matter how hard I try. Perhaps just like kimchi, the past should be buried, at least for now. Unearthed later, fermented, only when it is ready to be eaten. ///