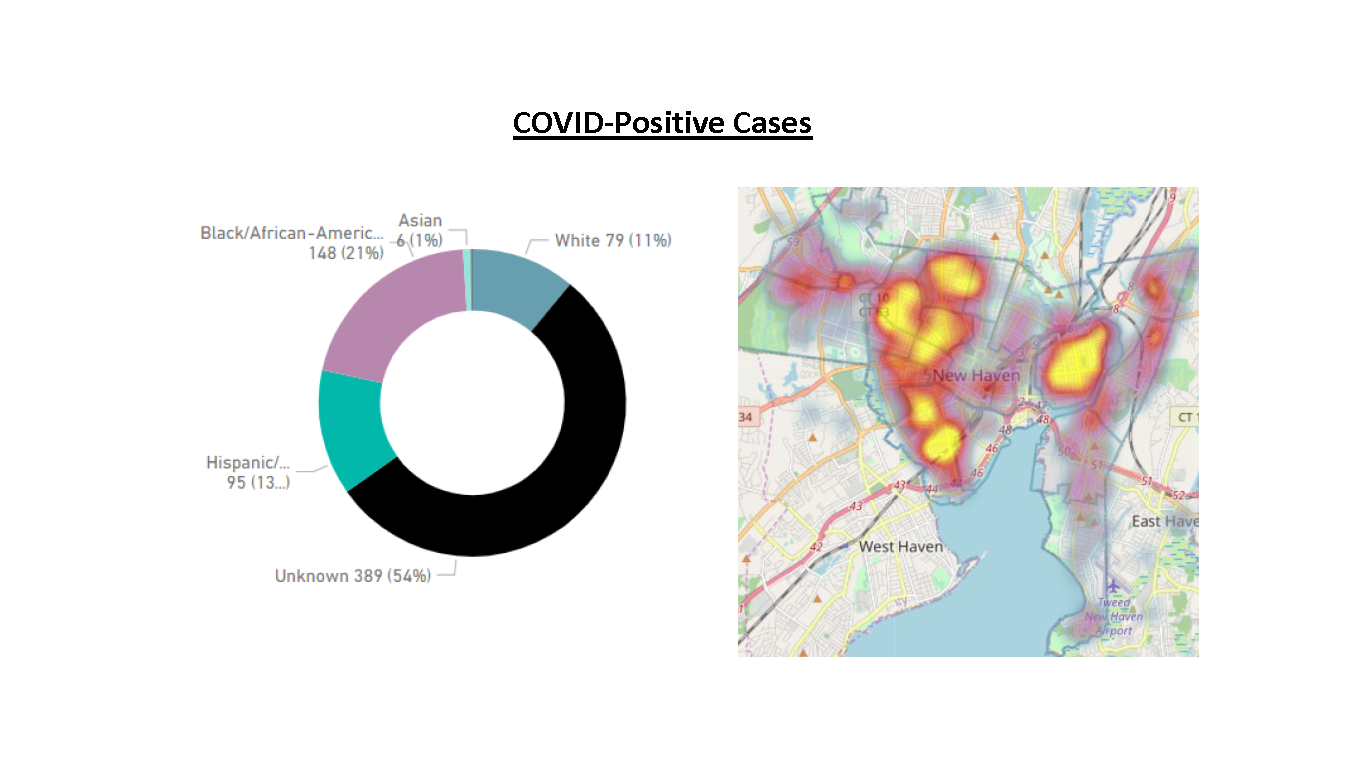

Last week, Mayor Justin Elicker released early demographic data for COVID-19 cases that indicates a disproportionate impact on black and Latinx New Haveners. But the race of 39 percent of patients was “unknown” at the time — now, that number has increased to 54 percent.

As of Tuesday, 389 of the city’s 730 confirmed coronavirus cases lack racial data. Still, current figures fit squarely within the existing trend in New Haven and across the country. With “unknowns” removed, black residents account for 45 percent of positive cases, 55 percent of hospitalizations and 44 percent of deaths. The figures for Latinx individuals are 30 percent, 36 percent and 19 percent, respectively. On the whole, the Elm City’s general racial breakdown is about one-third each white, black and Latinx. New Haven Health Director Maritza Bond said on Tuesday that the city is concerned about the lack of demographic data and has reminded testing sites about the importance of complete patient profiles.

“It’s a concern that we obviously have,” she said. “Because this pandemic evolved so quickly, individuals that are … submitting the forms are just moving too fast, and so it’s really a human error. We issued an email communication to those facilities about a week and a half ago, and now we issued a memo today to remind entities that it’s important to complete all the fields so that when the data does come in, we have a complete picture of the demographics that we’re looking for.”

Bond said that the problem is a statewide one, as the state surveillance system feeds information to local authorities. On April 13 — the most recent date for which Connecticut has provided racial data — there was no racial data for 7,141 of the state’s 13,381 confirmed cases.

Still, the city’s messaging was local, as local testing sites provide information to the state. Bond did not specify which sites received her Tuesday memo.

Yale New Haven Health, which conducts the majority of testing in the Elm City, did not immediately respond to the News’ request for comment. Fair Haven Community Health Center and Cornell Scott-Hill Health Center, which conduct smaller testing operations, also did not immediately respond.

Bond expressed doubt as to whether the city would ever recover complete information for current confirmed cases. It would require a “big lift” to get testing sites to backtrack and fill in missing data, she said while expressing her hope that testing sites improve reporting completeness going forward.

When asked whether the new unknown cases were all new patients, Bond explained that the city’s data fluctuates as it is cleaned. Other towns’ cases sometimes end up in New Haven’s system and vice versa. As such, New Haven could receive a test today that entered the statewide system last week, Bond said. This means that while the dates on all confirmed cases are accurate, a moment-in-time snapshot may not reflect all cases within New Haven’s borders.

The city has struggled with data accuracy in the past. Most notably, New Haven erroneously reported its second COVID-19 fatality on March 27 after receiving an inaccurate update from the state. On April 3, Elicker clarified that that patient remained in the hospital and said that the city’s health department would cross-reference fatality reports from the state with local death certificates before reporting fatality data.

As of Tuesday, New Haven’s official numbers indicate that 16 New Haven residents — seven of whom are black — have died of the virus. But according to local funeral home directors, the actual number of black COVID-19 victims is double the official one, the New Haven Independent reported.

The directors of Howard K. Hill Funeral Services and McClam Funeral Home report having buried 10 and four black individuals, respectively. Curvin K. Council Funeral Home, which also serves New Haven’s black community, did not immediately return the News’ request for comment.

In Tuesday’s press conference, Elicker said that such a discrepancy is a “real concern” if true and that he intends to look into the situation.

Elicker also offered some potential explanations for the gap in official and unofficial numbers. Some COVID-19 cases may not be formally identified as such, and some victims may say that they are from New Haven but reside within the region rather than city limits, he said.

The mayor has also consistently underscored that a lack of testing contributes to diminished reporting capacity overall — New Haven’s true numbers are likely much higher than what the city reports each day. Elicker has previously noted this problem with specific reference to racial data. One of his first steps in addressing disproportionate effects on New Haveners of color would be to stand up more testing sites in underserved neighborhoods, he said last week.

But in a Monday Zoom conference, local leaders and elected officials expressed their frustration with what they see as an insufficient official response to the crisis in communities of color.

“There’s a struggle with black and brown people,” the Rev. Boise Kimber said, according to the New Haven Register. “Something has to be done from a city standpoint and from a state standpoint.”

Kimber called for testing sites in predominantly black and brown neighborhoods, specifically Fair Haven, Newhallville and Dixwell. Existing data shows that these neighborhoods, along with the Hill, bear the heaviest concentration of COVID-19 cases.

In a Tuesday interview with the News, Elicker explained that the city’s data for these neighborhoods reflects all known cases — including those for which racial data is unavailable — because each reported case includes the patient’s address. He expects that the racial disparities reflected in the overall data are also reflected — and perhaps magnified — in minority neighborhoods.

State Sen. Gary Winfield, D-New Haven, said that state leaders can make an educated guess about the racial distribution of COVID-19 cases and respond with appropriate policies. But he underscored the need for increased testing capacity to inform official decisions about the efficacy of efforts such as drive-through testing sites.

Gov. Ned Lamont announced last Wednesday that CVS will open a testing site in New Haven with the ability to conduct 1,000 tests per day and process results in 15 minutes. The New Haven Register reported on Monday that the site, which will be located at Gateway Community College, will be able to accommodate up to 750 cars per day.