UP CLOSE

Yale Online: Can a remote education compare?

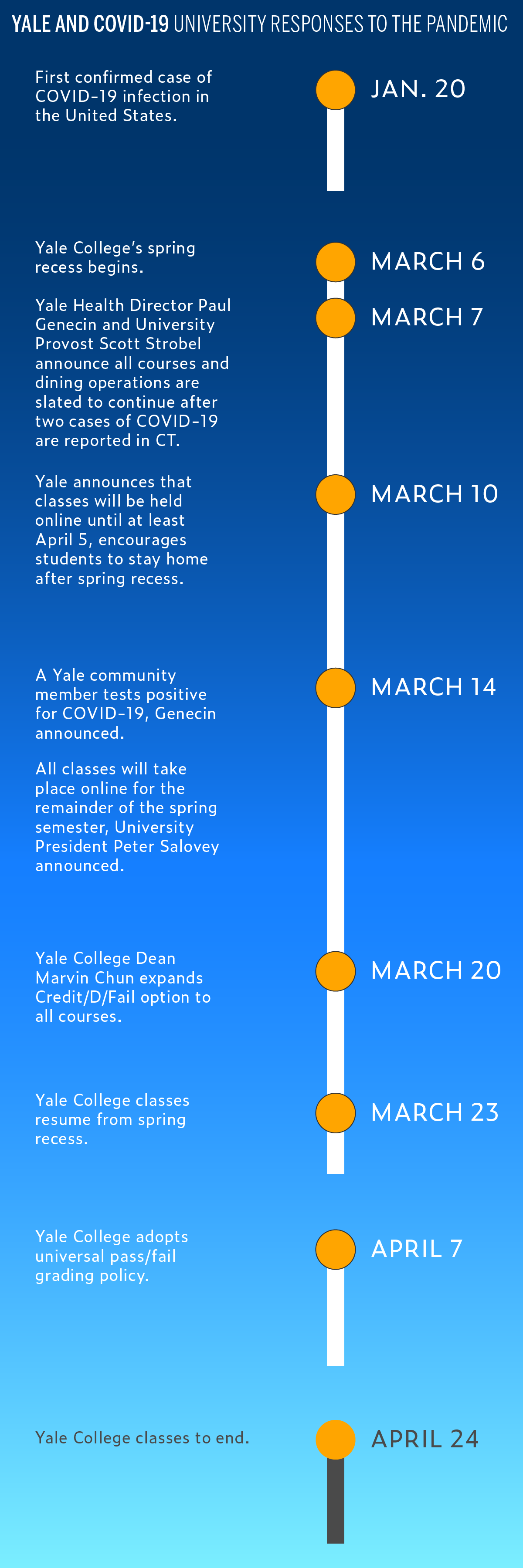

Teaching in the Ivy League may have changed more in the past month than ever before.

In front of a crowded bookshelf, history professor David Blight stands alone.

What was once taught in a packed lecture hall is now taught in an empty room, save for Blight and a masked camera operator. It’s his fourth recorded lecture on the Civil War. It’s the “Corona semester,” he says. A bright red bandana keeps slipping off his face.

“This is my handmade scarf,” he says to the camera, holding his bandana — a necessity during a global pandemic. “I wear it when I’m out in stores and so on.”

For the rest of the lecture, Blight’s scarf sits offscreen, as he speaks on the final days of the Civil War and the birth of Reconstruction. It’s a crisis that he knows well — one that is in many ways different than the pandemic currently ripping through the nation and the world.

But in the next video, the camera operator is gone. Blight stands unmasked, and teaches in his office on a Zoom call that’s set to be recorded and sent to students. Even having a cameraman in the same room, he said, was too dangerous. He greets his students with a sigh.

“I just want to wish you all, uh, good health out there,” he says. “I hope you’re all hanging in there.”

Instead of Henry R. Luce Hall, Blight’s lectures are now heard across the world. Instead of in-person section meetings, his students talk on Zoom. Fears over the spread of the novel coronavirus have shuttered University programs, tightened Yale purse strings and moved many of its signature courses online for the first time. Pushed out from campus, Yale students now Zoom into classes or watch prerecorded videos like Blight’s, transitioning to a virtual reality few colleges are accustomed to but most are experiencing.

But for a University that prides itself on its campus amenities, from communal residential colleges to stately lecture halls, the Yale education, like those of its peers in global pandemic, has become unable to offer students the same experience they had just months ago. Interviews with over a dozen administrators, students and faculty members describe a University greatly changed, as courses and programs struggle to survive in light of the novel coronavirus outbreak and economic downturn. Yale students and faculty have worked to adapt — rapidly changing their curriculum through doctored syllabi amid unprecedented shifts in the College’s grading policies.

Online classes — hardly the preferred mode of academic learning at a traditional institution like Yale — are now the norm. In little over a month, the virus has challenged the higher education system, called its value into question and altered its system for evaluating student performance. But as Yale waits out this pandemic along with the world around it, still some are left to wonder how long the restrictions will last — and how far-reaching an impact they may have on the University.

ONLINE CLASSES AREN’T NEW. THIS IS.

French professor Alice Kaplan has taught about plague and crisis before. Now the chair of the French Department, she has taught some of France’s hallmark texts following the Great Recession and, now, teaches amid a global pandemic that has infected around two million people across the globe.

But the impacts of this crisis are markedly different, and her plans for the semester have shifted. The syllabus for her course “The Modern French Novel,” crafted well before the pandemic, includes Albert Camus’s The Plague — a 1947 novel about a virus that rips through a small French village in Algeria. She said she cannot teach the book like she has in the past.

“I could not use the same lecture I used before,” she said. Isolation is a key theme in the novel. But the coronavirus outbreak, she said, which has forced much of the world’s population inside of their homes, seems quite comparable. “We’re living through a more radical isolation.”

Even when Yale was briefly dismissed amid fears of a British invasion during the Revolutionary War — which eventually happened in 1779 — University leaders encouraged students to live and study with their tutors further inland. Some could later stay home and study from books, but they had to pass an exam to advance. Facing crises yet again in the 20th century, Yale took alternate measures — shipping its students-turned-soldiers abroad and shortening the time it took to receive a University degree. The Spanish Flu, which erupted in 1918, forced Yale to cancel all on-campus public meetings, forbid community members from interacting with New Haven residents and isolated students and professors. Only a handful of Yale students died from the virus, thanks in part to the military’s presence at the University after World War I and its strict regulations. And following World War II, Yale’s lecture halls surged with veterans armed with G.I. Bill benefits — according to a YaleNews article, some 8,000 students came to the University in 1945. Most were service members.

While this pandemic has caused one of Yale’s most drastic responses yet, not all of the changes are new. Yale professors have made brief dips into online learning through Massively Open Online Courses on websites like Coursera. Anyone with a stable internet connection can now, for a fee, be a Yale “student.” From “Introduction to Psychology” to “Roman Architecture” to “The Science of Well-Being,” enrollees can read, listen and learn from the University’s top professors — all without earning a degree.

Harvard professor David Malan sees the value in online learning. His computer science survey course “CS50” is almost entirely taught online — from the lectures to the problem sets. Aside from an all-night Hackathon and weekly section meetings, students can complete nearly the whole course from their computer. Yale has its own successful version of the program — which had nearly 230 enrollees last fall according to Yale’s Course Demand Statistics.

Malan told the News that the course’s use of technology is “additive, not subtractive” for most students.

“After all, it’s so common for all of us to miss or misunderstand some detail in class, particularly when classes are long, if not dense,” he wrote. “Even the simplest of features online, though, allow students to rewind, fast-forward, pause and look up related resources.”

Still, five senior Yale professors interviewed by the News by and large consider online classes as no substitute for a University environment, with its face-to-face interaction, dorm-room conversations and strolls through the Sterling stacks.

Kaplan and Blight are two of many professors across the University whose classes — and teaching styles — have drastically changed in light of the coronavirus outbreak. But this move has also brought unintended consequences. Students are less engaged, said Maurice Samuels, a French professor and Kaplan’s co-instructor. Reading attracts less focus. Attention spans thin, Samuels added.

“It’s not ideal. I would be very, very sad if we had to do this for more than these few weeks,” he said. “A lot is lost from not being there in person.”

A CLUNKIFICATION

Philosophy professor Shelly Kagan teaches some of Yale’s most popular introductory philosophy courses, including “Moral Skepticism” and “Introduction to Ethics.” His students call him Shelly. He sometimes starts his lectures sitting cross-legged on a wooden table in the front of the room. On a normal day — that is, when classes are in-person — he will walk from one end of the room to the other to connect different arguments to physical locations. Near the door, nihilism; moral noncognitivism in the center; another toward the windows. He maps arguments on the blackboard. And while he’s teaching, Kagan said he likes to see his students’ faces to see what clicked — and what needs more explaining.

Kagan can lecture in front of hundreds, even thousands, he said. But for the seasoned professor, Zoom conferences have proven challenging.

“I don’t know whether my jokes are falling flat. But more importantly, I don’t know how my ideas are coming across.”

—Shelly Kagan, philosophy professor

The lighting is different in everyone’s video feed, he explained. Someone forgets to mute their mic. There’s a delay over the internet — however small — that does not happen in-person. Minor inconveniences, he said, “but it adds up.”

Video conferencing software “clunkifies” teaching, he said. “I can do this in this tiny little box you’re seeing,” he told the News via Zoom call, his hands poised eagerly in front of a web-camera, “but it’s a lot different. I find it very clunky.”

Kagan was one of the first Yale professors to upload a course online, for free, to the public. Called “Death,” his Spring 2007 lectures were recorded and distributed on Youtube the following year. Its first video has over 1 million views.

One semester, Kagan said he taught his “Death” course to a class that included a dying student who later passed away during the semester. When he recounts his experience to later classes, he said, the lecture hall goes silent.

From a Zoom conference call, where he can only see a small section of his students through the user interface, Kagan predicts those moments happening online would be far more difficult.

“I don’t know whether my jokes are falling flat,” he said. “But more importantly, I don’t know how my ideas are coming across.”

One of the more major changes at Yale this semester has already happened. After weeks of debate and three surveys, Yale College Dean Marvin Chun announced students would forgo letter grades this semester and instead adopt a binary “pass” or “fail” policy for all classes.

Many students celebrated the change. A Yale College Council poll conducted late last month revealed that nearly 70 percent of its 4,544 respondents supported a similar “universal pass/no-credit” policy. Advocates emailed professors and spread petitions, inspiring similar movements across the nation.

But the policy was a tougher sell among Yale’s faculty members. An initial survey of 340 faculty members showed only 28 percent supported the change late last month. Following two meetings and another survey, Universal Pass/Fail was adopted with 55 percent of 536 faculty respondents’ approval. While the universal system did attain majority support, three professors interviewed by the News said they fear students will check out of their classes, knowing they are likely to pass.

Computer science senior lecturer James Glenn told the News that the change comes just as his store of material he had prepared over spring break had run out. Glenn teaches “Algorithms,” a lecture course that counts over 100 enrolled students. Now that the policy has changed, he wrote, “I fear they’ll disengage just as we’re getting to some of the most important topics in the Algorithms course.”

Some faculty were more optimistic. History professor Anders Winroth, who teaches the popular “Vikings” lecture, wrote in an email to the News that he does not think things will change dramatically.

“Students who are devoted to learning will want to continue as they have before,” he wrote. “Again, the real change is for those whose lives have changed fundamentally.”

A FUNDAMENTAL CHANGE?

Some professors have decided to forgo live discussions entirely, since many professors have broad discretion over how to run class in the time of pandemic. Still, the pandemic poses challenges far graver than just a shifted schedule.

History professor Carlos Eire, who now records his lectures in advance, has made a contingency plan for his teaching assistants to follow in case he gets sick, he said. Since his age group is vulnerable to COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, these lectures are held virtually in what he calls “the vault:” a repository of class files that can be accessed without him.

“If I do come down with it,” he said, “I want to make sure I have the lectures [there].”

Yale’s older professors are especially vulnerable to the disease caused by the coronavirus outbreak. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control, COVID-19 hospitalizes between an estimated 31 and 59 percent of senior citizens aged 65 to 84 who contract the disease. For a faculty population that skews older, the threat of the virus brings further questions over how the Faculty of Arts and Sciences will deal with potential loss of life — slightly less than one-third of FAS ladder faculty fall into this vulnerable population group, FAS Dean Tamar Szabó Gendler told the News.

Gendler asked all faculty to develop plans in case of sickness or caretaking late last month. Among the guidelines, the Dean recommended that professors nominate another instructor in their subject area to take over their classes should they be unable to instruct them.

“Putting such contingency plans in place is difficult but necessary, and it is my hope that all of us remain in good health,” she wrote to faculty on March 27. “However, I also hope that putting contingency plans in place now can alleviate some anxiety and uncertainty in the weeks ahead.”

Gendler also provided accommodations for tenure-track faculty in recent weeks, extending their tenure clocks by one year for most professors in response to the coronavirus’s chill on University research. But those on the lower rungs of the academic ladder — graduate students and instructional faculty — said they have yet to see their concerns assuaged.

“If I do come down with it, I want to make sure I have the lectures [there].”

—Carlos Eire, history professor

Lecturers and other contract instructors account for much of the FAS. These non-tenure-track, instructional faculty members have renewable contracts, and their work with the University provides healthcare. But faced with a provost-imposed hiring freeze until July 2021, some of these instructors may soon find themselves unemployed — and without health benefits — in the time of a global pandemic.

Instructional faculty members have begun to circulate a petition across the University to extend or renew their appointments through the next academic year. So far, according to one such faculty member, over 800 people have signed it. Provost Strobel did not respond to a request for comment.

“We ask that the University administration make good on its word by using its considerable resources to extend the appointments of existing instructional faculty by one year,” the petition states. “These acts literally could be life-saving.”

A YALE ONLINE

Before Peter Salovey assumed his position as University President in 2013, he told the New York Times that he saw online classes as a potential University priority for the future. Under his leadership, he anticipated that Yale would adopt a “deliberate strategy for giving the riches of Yale, the wealth of Yale, away” — a goal aided by broader availability of online learning, he explained.

Eight faculty members interviewed by the News said that this crisis is their first experience with online instruction and its challenges.

But Stanford University associate professor and expert on college innovation Mitchell Stevens said this time can be a testing ground for broader involvement in online education. As asynchronous learning options become more convenient and accessible to the general population, Yale can follow suit, he said.

“The mistake that a lot of academics in traditional classrooms make is they presume that every kind of instruction requires — and is best delivered — in person. We know that’s not the case,” he said. “Elite schools have been snobbish about this for some time.”

Not only are online classes better for some disciplines, Stevens said, but they are also far cheaper than in-person instruction. Grand lecture halls and intricate landscaping are less necessary when interaction with faculty members is limited through a webcam. Yale and other top-ranked institutions are not just selling an education, he explained, and they rely on the college experience to justify the price tag.

But when in-person contact is impossible and Yale’s libraries are closed, several faculty members told the News that distance learning has raised questions over the monetary value of a Yale education.

In an email to the News, FAS Dean of Undergraduate Education Pamela Schirmeister said that the University is not a distance-learning institution that “routinely and/or solely” educates students online, and that her team is working “as hard as we can” to make sure instruction continues in light of the pandemic.

“We cannot simply abandon any attempt to continue instruction,” she wrote. She pointed to a recent internal survey that showed faculty felt remote teaching was working “fairly well, given the circumstances.”

Stevens said he hopes the coronavirus crisis renews Yale’s interest in online courses — a cheap way to, as Salovey said in 2013, give Yale’s wealth away.

“We cannot simply abandon any attempt to continue instruction.”

—Pamela Schirmeister, FAS Dean of Undergraduate Education

“I don’t think we’re all going to just go back to normal in any institutional domain,” he said. “Wars and calamities change institutions, and this is certainly a calamity.”

Malan, the Harvard computer science professor referenced earlier, said that video conferencing “isn’t yet great.” Still, he added it has room for improvement, especially with advances in audio and video.

“In the meantime, it’s pretty good and surely, for some courses, more compelling than purely asynchronous experiences,” Malan said. “And, while we’re all pretty weary lately, I’m sure, of video conferencing itself, that won’t be the case forever, particularly once the technology gets out of the way and we can interact with each other all the more seamlessly digitally.”

That said, Malan also agreed that there’s a value in having a “shared, educational experience” in person. CS50’s lectures are still held at Harvard and at the start of Yale’s term. “Should more courses, then, leverage technology? Probably, if it makes sense and actually solves a problem,” he wrote.

Kagan, too, has wondered about the future of learning. Decades ago, when handheld calculators dropped enough in price to make owning one less expensive, he said he remembers asking similar questions. “Would this fundamentally alter the way we understand math?” he asked, holding a grey one of his own during a grainy Zoom call.

The same may be true for online classes, he said. But he may not be alive to see it: “Maybe it’s [that] old codgers like me die off while thinking person-to-person interaction is better,” he explained.

The coronavirus has scattered the Yale community. Still, the internet has kept faculty and students together — reading, opining, speaking and learning from online conference calls across the world. Meanwhile in New Haven, despite the worries and fears of a global pandemic, the tulips are still in bloom. Spring seems to march on even when few can see it.

In a recent Canvas post to students in the Civil War class, Blight pointed to the season with gentle optimism. He sent a recording of a cardinal chirping among tree branches, and a poem about a bluebird that still sings in a world where questions remain unanswered.

“Nature is having its rebirth,” he wrote. “Our society will too.”