Courtesy of MakeHaven

MakeHaven, an Elm City makerspace, has fully devoted its resources to responding to COVID-19. Within the last few weeks, the non-profit’s large volunteer base has sewn cloth facemasks, produced plastic face shields, prototyped and produced intubation shields and worked to produce respirators that rival the standard N95 in quality.

MakeHaven’s COVID-19-related endeavor started with producing facemasks. According to shop manager Lior Trestman, after MakeHaven’s three staff members closed the venue’s doors, they cobbled together instructional videos on how to sew reusable face masks. They then reached out to community members with the help of United Way and soon recruited enough volunteers to gather a virtual sewing circle over Zoom.

In order to prevent spreading the virus, staff members established four porches across New Haven as pick-up and drop-off locations. Volunteers can pick up materials from a box placed on these porches without interacting with another individual and drop off completed masks.

Volunteers with the means are asked to sterilize their masks in washing machines upon finishing them and seal them in a plastic bag. MakeHaven staff members pick up the finished masks from the porches, wash the unsealed ones and distribute them to non-profits across the city.

Among MakeHaven’s sewing volunteers is Liz Saylor, the costume designer at Ivoryton Playhouse. Through its new program Sew Good, MakeHaven may pay her and other professionals for their time with donation money, though Saylor is unsure whether she feels comfortable accepting any compensation.

New Haven’s Downtown Evening Soup Kitchen (DESK), one beneficiary of MakeHaven’s mask and face shield distribution service, has received numerous masks and had its first three face shields delivered on April 8. The kitchen’s employees and volunteers require masks for protection, and any additional masks are distributed to the community members they serve.

Steve Werlin, DESK’s executive director, said he was very impressed with how quickly MakeHaven realized the need for more protective gear and began producing it. DESK especially requires protective gear right now, as it is currently intaking — or, conducting initial case assessment interviews — for various social programs. Part of the intake process involves gathering information from DESK’s clients, which is a difficult task when attempting to maintain social distance.

“The notion of social distancing really has to go away when you talk to someone,” said Werlin. “You need that body language of trust, so to be safe we really need face shields and not just face masks.”

MakeHaven has also donated face masks, face shields and intubation shields to the Yale-New Haven Hospital. MakeHaven sewers use two patterns to create face masks — one is a simple cloth rectangle for pedestrian use and another more complicated model is intended for health care workers. Dr. Lisa Lattanza, the chair of orthopedic surgery at the Yale School of Medicine, said that even the latter model does not filter small enough particles to be used in some hospital settings. These require the more sophisticated N95 respirator. Even so, she said these masks can be used to cover other, higher-quality masks, shielding them from contamination so they can be reused.

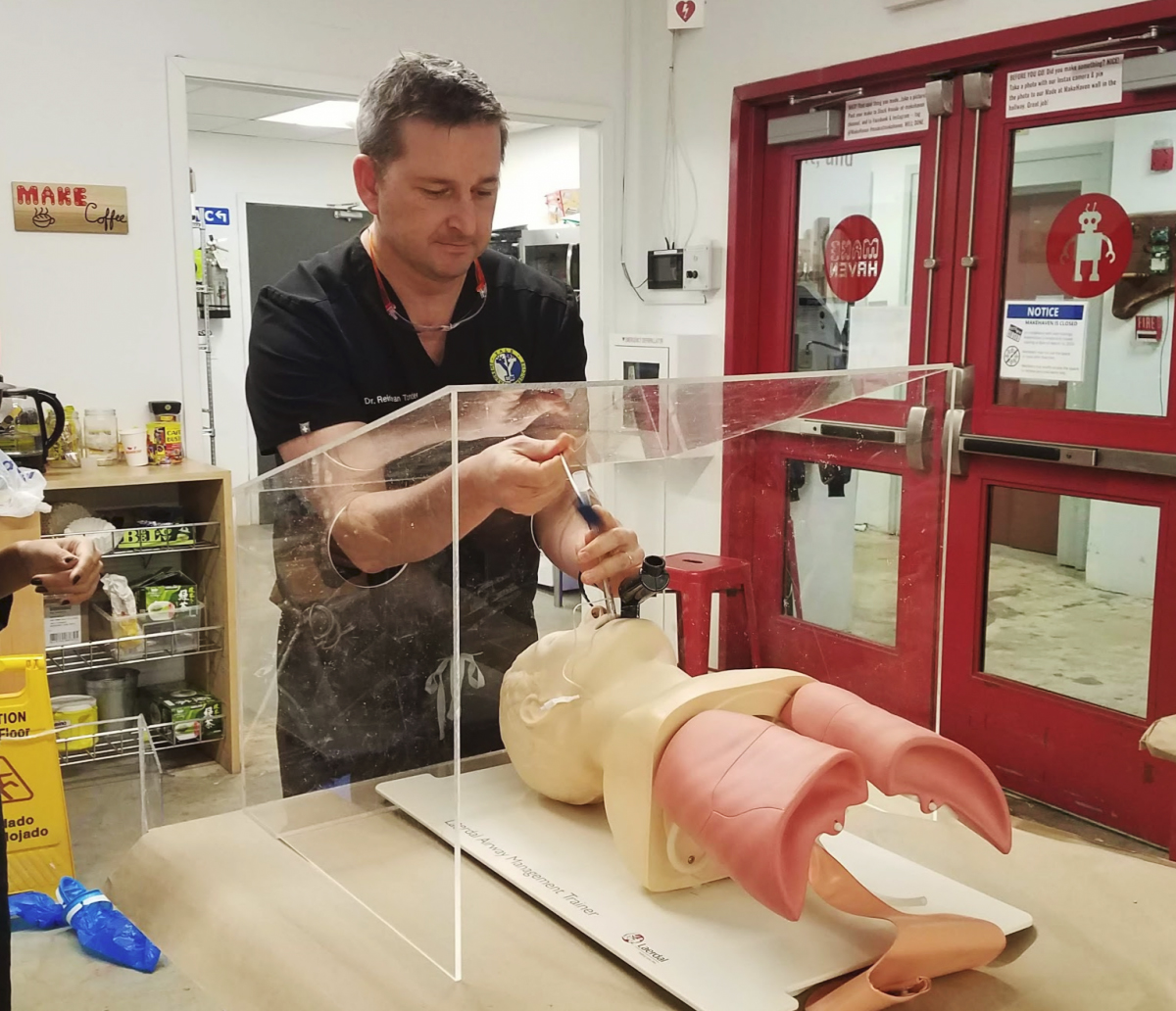

Dr. Lattanza was particularly excited by MakeHaven’s creating plans for and producing intubation shields – clear plastic boxes that go over a patient’s head during the risky intubation procedure – as there were previously no such shields that fit the dimensions of Yale New Haven Hospital beds. Successful iPeople at MakeHaven are also attempting to 3D print COVID-19 testing swabs and to produce a ventilator very similar to the preexisting AmboVent.

MakeHaven’s attempt to produce a respirator that rivals the N95 in terms of filtration ability is similarly in-the-works. The effort comes after The Yale Center for Engineering Innovation and Design, or CEID, was one of the first centers in New Haven to undertake the project in New Haven after it became apparent that current respirator production was insufficient. However, Dr. Lattanza said that after a few weeks, the CEID decided to devote its resources to testing ventilator prototypes rather than creating them, since the CEID’s equipment is uniquely well-suited for the job. Since then, MakeHaven, in collaboration with doctors from the Yale-New Haven Hospital and Yale engineers, have adopted the project of producing the respirator.

Producing a respirator that filters particles as small as the N95 does is difficult for two reasons, said Dr. Lattanza. To protect doctors from potential infection, the ventilator’s mouth-piece must be soft enough to conform to a patient’s mouth. 3D printing design, what would otherwise be the most obvious choice for easy prototyping and production, uses plastics that are much too rigid. Secondly, the N95’s filtration material is difficult to replicate in a setting like MakeHaven.

“You can’t just go to JOANN Fabrics and buy N95 respirator material,” said Dr. Lattanza. “I wish you could.”

Though the maker space is still producing face shields, MakeHaven staff members do not want to devote too many resources to creating what manufacturing spaces can create with more efficiency. Rather, they want to continue working on prototypes for new equipment and then pass these plans to manufacturers.

“We see ourselves as filling in the gap until the larger supply chain can do that,” Cebik said.

New Haven manufacturers have begun mass-producing the face shields that MakeHaven produces, but according to MakeHaven’s operations manager Kate Cebik, no manufacturer has begun mass-producing intubation shields.

Annie Radillo | annie.radillo@yale.edu