Isabelle Lin

The sun is shining, the birds are chirping and we’re ankle-deep in litter and dead leaves in the Fair Haven neighborhood of New Haven. A doll’s head protrudes from the muck, encircled by shards of broken beer bottles. We peer through a chain-link fence out over the Mill River to Ball Island, where the building stands.

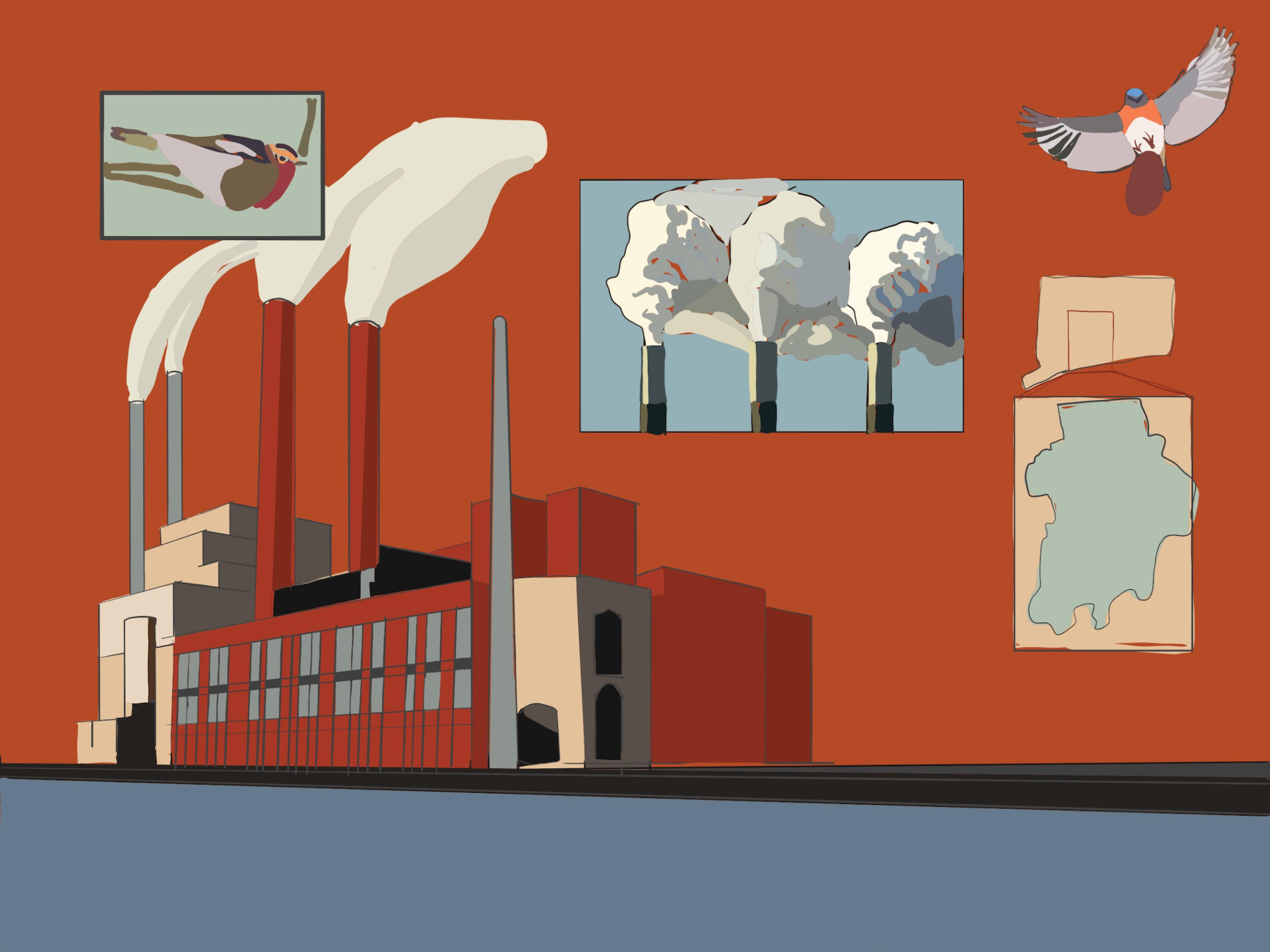

Two smokestacks rise from the art deco frame of the building, broken windows visible even from across the river. There are gaping holes at the structure’s edges wrought by the odd scrap metal scavenger, arriving at the island by boat to pilfer and recycle what’s left of the edifice. A century ago, this portrait of urban decay was inaugurated as English Station: an industrial vehicle that powered New Haven and surrounding towns through the twentieth century.

The decommissioned coal- and oil-fired power plant looms over the Grand Avenue bridge and surrounding buildings, most of them squat and industrial — a mechanic’s garage, a paint shop. A block away, children are running around on playgrounds at two different elementary schools.

Christopher Ozyck, a community greenspace manager at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, offered to show us around Fair Haven for the morning. A resident of Fair Haven Heights, Ozyck can see the English Station smokestacks from his bedroom window.

“For the last almost-100 years, [English Station] was operating and polluting this neighborhood, and that’s a long legacy,” Ozyck says. “You can’t just walk away from these things — you have to have some sort of moral [obligation] to clean it up and honor the legacy of the burden that this community has borne.”

Ozyck’s 96-year-old neighbor, Gladys, has lived in the same house in Fair Haven for 65 years. She remembers a time when smoke drifted from the plant and into the sky, tinting the winter snow with industrial soot.

English Station was commissioned in 1924, activated in 1929 and breathed its last in 1992 when the plant’s operator, United Illuminating, found it too costly to keep the furnaces alive. During the plant’s 63 years powering the Elm City and neighboring townships, countless pounds of asbestos and PCBs — a chlorine-based industrial chemical — became part of the Ball Island landscape, imperiling the surrounding Mill River watershed and neighborhoods on both sides of the plant.

The property has changed hands several times since its initial sale in 2000. According to the New Haven Independent, the property’s current owners have eluded direct engagement with both the community and the city at large. Because the site is private property, New Haven can only do so much to regulate the site and plan its future.

Situated only one mile from the Green, nine-tenths of a mile from Frank Pepe’s Pizza and around the corner from the John S. Martinez Sea & Sky STEM Magnet School, the site’s position in the city locates it among the centerpieces of New Haven and the lives of over 130,000 people.

“No Fishing From Bridge”

We leave the chain-link fence and make our way back to Chris’ truck. The crunching sound of our shoes on the leaves and beer bottles resounds in the bright, still February morning air — from here, the site seems quiet, even peaceful.

In 2000, United Illuminating transferred ownership of English Station to Quinnipiac Energy, a local utility company. According to the New Haven Independent, UI paid the new owners $4.3 million to take over the site — which had become one of the dirtiest power plants in the state by the time of its decommissioning.

Back in the truck, we drive around the site and up onto Chapel Street’s crossing over the Mill River. From the bridge, you can see English Station in all its dilapidated glory — the crumbling bricks, the broken windows. A team of orange-vested construction workers is laboring away at piles of salt that coat southern New England’s roads in the winter.

A sign proclaims, “NO FISHING FROM BRIDGE.” Still, fishing lines hang from the railings, dipping down into the water below. There is no signage warning fishermen or passerby about the toxins leaching from English Station into the river.

“I think everybody’s concern is that if the river doesn’t get cleaned up, this will be an ongoing issue for people for generations,” Chris says. “[English Station] had a long-lasting legacy of all the pollutants that were dumped in this neighborhood, and so those health impacts have been generational — [the pollution] affects the quality of the housing, it affects the soils around the houses.”

After the plant was decommissioned, it took over 20 years for efforts to rectify the near-hundred year history of latent toxicity at the site to begin. Only when UI entered into a partial consent agreement with the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection in 2015 did English Station begin to benefit from any cleanup. Per the parameters of the partial consent agreement, UI is responsible for up to $30 million in remediation efforts on the site.

UI spokesperson Ed Crowder told the News that to date, the company has removed concrete floor surfaces and fire transformers, cleared out 15,000 bags of asbestos and other waste materials, demolished the Station B structure (a smaller auxiliary edifice fronting Grand Avenue) and is continuing to sample soil and groundwater.

In an email to the News, Crowder said that the company is working in coordination with DEEP as they pursue “important environmental remediation work in the Fair Haven community.” He added that UI meets with DEEP on a monthly basis, if not more frequently, to discuss the remediation effort and ensure its compliance with federal and state regulations.

Looking out over Mill River, Ozyck tells us that today’s high tide conceals the pipes leaking sediment into the river. He gestures toward the bulkhead abutting the island’s juncture with the river, explaining how PCBs — which were sprayed on the island to prevent coal ash from being carried off by the wind — bind with organic materials, complicating the ecosystem of the Mill River.

Kat Fiedler, a legal fellow for the Connecticut Fund for the Environment (Save the Sound), said that her organization’s primary concern at the moment is making sure the remediation effort does not negatively impact the river.

“The focus right now is to make sure the island is cleaned up and the river is clean, ensuring no continued migration of contamination from the site to the river, if there even is a true boundary between the island and the river itself,” Fiedler said. “We’re tracking [UI’s] remediation schedule, as there is a proposal to extend it … it’s important to make sure the island is on schedule so we can move onto the river.”

Fiedler’s concerns with the river are rooted in the remediation effort itself. The partial consent order did not require UI to tend to the river and there is no extant set of data on the river’s ecosystem from the start of the remediation process. This means it will be difficult for Fielding and other activists to track the progress of the ecosystem’s health as sediment could be leaking into the river. Fiedler said that when there is no background information, it becomes difficult to confirm that the protective measures to prevent further migration of contamination are actually working.

While several activists and community members remain concerned about the remediation process, others are considering the social role of English Station.

“Fair Haven: Historically First”

A two-minute walk from the Mill River’s shore, children are running around on the playground outside John S. Martinez School. Teachers and parent volunteers huddle in groups to stay warm, chatting and keeping an eye on the scene.

Cold Spring School, an independent school for preschoolers through sixth graders, is just down the block. One the side of one red-brick building, a mural depicts multicolored reeds blossoming against a sky-blue background — one day, Mill River might be healthy enough to sustain such life again.

We’re parked across the street from both schools in Chris’ truck, discussing Fair Haven’s relationship to English Station. He said that he believes it’s time for the city government to get involved with the remediation effort — that, in fact, this may be New Haven’s last opportunity to engage with UI on this issue in a meaningful way.

Hopping out of the truck, we talk as we walk around the neighborhood. In the span of several blocks, we pass two churches and two auto body shops. On the corner, there’s a tall green iron post with a bright blue sign at the top: a sketch of two sailboats sits above the words “Fair Haven: Historically First.”

Chris tells us about the cohort of activists that have been shaping the conversation about English Station’s future. There’s Anstress Farwell, the president of the New Haven Urban Design League, who sent the News an archive’s worth of documents regarding the history of the English Station site; community activist Aaron Goode ’04; former secretary of the Fair Haven Community Management Kimberly Acosta; and countless other figures that make up the shores of the Mill River.

“We’re looking for three things [from UI],” Chris says. “One is to clean up the island to an acceptable level. [Two], to clean up the river. Three, to create a legacy fund for the long term impacts of this facility on the Fair Haven neighborhood.”

By the time we return to the truck, the kids have gone back inside their respective school buildings. Recess is over.

Kimberly Acosta has lived in Fair Haven for most of her life, two blocks from English Station, to be exact. As secretary for the Fair Haven Community Management Team, she engaged with community leaders committed to voicing their concerns about the site. She said that while there is a bright community of activists, she doesn’t think that group reflects the voices of those who live closest to the site and are therefore most impacted by it.

“That extends to the people who fish in the water,” Acosta said. “[There] hasn’t been much done on the city’s part or DEEP’s part to kind of make signage and make it clear that it’s not okay. People are fishing.”

Acosta highlighted the disconnect between those who fish in the river and those who are striving to prevent the contamination from impacting the community. What concerns her is ensuring that the people who are the most impacted by the contamination and are fishing in it are present in the cleanup efforts. She prioritizes the community being able to question and understand what’s going on.

UI spokesman Ed Crowder also stressed UI’s commitment to keeping the local community and city officials in the loop, especially emphasizing providing materials in Spanish as well as English.

“I would say the average citizen wouldn’t know because the information isn’t very accessible,” Acosta said. “Something that has been suggested is there being paperwork available on the site … I don’t think it’s been made clear that it’s PCB polluted.”

Acosta said she and other activists hope Mayor Justin Elicker, FES ’10 SOM ’10, and his administration will learn more about the English Station and those who live closest to the site.

In an interview with the News, Elicker said that he was not yet informed about the situation at English Station.

“This is an issue that I’m not yet fully up to speed on,” Elicker said. “Any property owner has significant liability when there are pollutants on the property. So, as far as I know, there’s been no consideration of eminent domain on this site. The site has incredible potential because of its access to the water and its proximity to downtown.”

Elicker added that it is important to his administration that UI follows through on cleanup on its side.

What happens next?

Our last stop is a public access path along the Mill River, several blocks from the plant. The path is a community project, a still-in-progress effort to connect Fair Haven with the East Rock neighborhood. People fish here, too, Chris tells us, and sometimes in the summers he sees them swimming in the river.

There aren’t any notices about English Station posted along this path, either. There is another sign, though. It’s light blue, adorned with hummingbirds, butterflies and environmental conservation tips. A small map depicts the New Haven Harbor Watershed, and a graphic explains the seasonal migration patterns of birds.

“Welcome to a New Haven Urban Oasis!” the sign exclaims.

Elihu Rubin ’99 — an associate professor of urbanism at the Yale School of Architecture — has been involved with the English Station site for several years now. He is among those who see English Station for what it could become in the post-industrial landscape of New Haven despite the real environmental challenges it faces today.

Rubin hopes to see the building preserved, and for Ball Island itself to become a public park. As a habitable landmark, he envisions the space becoming a museum of science and technology, or a rock and roll venue, among other potential uses.

Rubin is not alone in his thoughts for the site’s future. Former New Haven Mayor Toni Harp ARC ’78 once supported a repurposing concept in which English Station would become a microbrewery, according to the New Haven Independent. There are still no concrete plans for the site’s future, however.

“Concerns about remediation transcend the site itself … I don’t want to see the building be torn down because the owners say it had to be torn down because that was the only way to remediate the site,” Rubin said. “We already lost Station B, which was a wonderful building, in my opinion that fronted Grand Avenue that was torn down as part of the remediation. to remediate the site, we have to tear down the building. And I really don’t want them to say that about the station, it would be in my, in my view, a terrible loss. It’s a real landmark.”

Rubin continued, “And now the challenges are how do we communicate the beauty, the intrigue, the potential of this structure. I think that there are so many intersecting issues at the site and some of them do involve contamination, public health and environmental justice.”

Among the challenges he identified is the disconnect between activists and residents most directly affected by the contamination. He said that while there are many New Haven based “quasi-activists” who regularly attend public meetings and practice civic engagement, there are also locals who might be impacted by that site by virtue of the environmental health issues; they may not be accustomed to going to these public meetings or getting engaged in this way.

For Rubin, this raises the questions like, “Who is the public?” and “Who gets to represent themselves as the interested public?”

Many post-industrial American cities are in the process of reclaiming their waterfronts and converting brownfield sites like English Station into assets, Rubin said. He suggested that the Mill River could become the “jewel” that anchors this section of the city.

Rubin acknowledges that the challenge here lies in inviting a broader public, including the people that live closest to the site itself, to engage with the history, the politics and the proposals that will shape the English Station site. As for the city’s role in the site’s development and questions of eminent domain, Rubin advocated for a realignment of the site’s ownership to accommodate the public interest.

“I know this flies in the face of the American way or private property and other stuff,” Rubin said. “But I don’t think that these two private owners should own the law. I think that this should be used as a case study in environmental remediation and returning land into public use.”

One major aspect of the heritage of industry according to Rubin is environmental health hazards, and the impacts of these hazards are not distributed equally in the city. It affects the people who live nearby. There are industrial and power generating areas that are distinct from the wealthier areas of the city. He posited that there is a reason why the ritzier Prospect Hill is Prospect Hill, and there’s a reason why the areas near the Mill River are the way they are.

“One of the first things I would do right away is to light English Station at night, and to let people see it,” Rubin said. “And to allow the building to become the kind of a landmark or beacon that it really could be.”

John Besche | john.besche@yale.edu

Olivia Tucker | olivia.tucker@yale.edu