For the first time since 1920, a Torosaurus skull was taken out from the Great Hall of Dinosaurs at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. It is currently on view at the Yale University Art Gallery, as part of a new exhibition called “James Prosek: Art, Artifact, Artifice.”

The exhibition — curated by James Prosek ’97, an American artist, writer and naturalist, and Laurence Kanter, chief curator and Lionel Goldfrank III Curator of European Art at the YUAG — showcases Prosek’s work alongside objects from the YUAG, Peabody and the Yale Center for British Art. In combining these collections, Prosek seeks to challenge the traditional distinctions between “art” and “artifact,” or “natural” and “man-made.”

“I have a deep love for the natural world, and I hope that whatever I put together conveys that,” Prosek said. “A lot of the show is about the tension between the named world and the natural world as it was, before we put names on it. The problem of living in a world of language is that we sometimes come to prefer it over the real world.”

The exhibition, on view until June 7, displays nearly 100 objects. About a third of these are Prosek’s works, including watercolors, canvases, collages and sculptures. Other artists featured are Paul Gauguin, John Constable, Martin Puryear, Helen Frankenthaler, Albrecht Dürer and Jackson Pollock.

Prosek described the show as a “dream project.” Since he grew up in Connecticut, the YUAG and Peabody were the first museums he ever set foot in. He developed intimate connections with both museums during and after his time as an undergraduate at Yale. Prosek was a curatorial affiliate in the Peabody’s vertebrate zoology department in 2011 and was the YUAG’s Happy and Bob Doran Artist in Residence in 2018.

Prosek was invited to the residentship by the YUAG’s former director, Jock Reynolds. Reynolds encouraged Prosek to work toward a show combining objects from the YUAG and Peabody with his own work. Reynolds soon retired, but Prosek said the YUAG’s current director, Stephanie Wiles, continued to demonstrate a keen interest in his project because it integrated objects from different Yale institutions.

Kanter noted that this exhibition is “well outside” the gallery’s regular scope of operation. He said that even though the YUAG has collaborated with the Peabody in the past, it has never been on this scale. Kanter believes this is a promising avenue for similar projects in the future.

“An exhibition like this is relevant anywhere,” Kanter said. “It encourages, or even forces visitors to think about things they’ve taken for granted in a new way. There is material here that I think most people would never expect to encounter at an art museum.”

Prosek has always felt intimately connected to nature. His experiences growing up, ranging from fishing and bird-watching to specimen collecting, inspired him to question human interactions with the natural world. The exhibition explores tensions between nature’s inherent interconnectedness and its fragmentation through taxonomy. Prosek invites visitors to consider the human urges to represent and classify nature, and the extent to which these classifications can limit their experiences of the natural world.

In the show, the Peabody’s Torosaurus skull lies alongside a sculpture made by British artist Barbara Hepworth. Prosek juxtaposes man- and nature-made objects at several instances — for example, a bird’s nest with a human-made basket and natural patterns on birds’ eggs with 20th-century expressionist paintings.

Wiles described the exhibition’s juxtapositions across time and media as “fascinating.”

“[The show] rewards close looking and inspires the visitor to take time — not only to experience the beauty of what’s on view but to carefully detect what is natural and what is fabricated,” Wiles said.

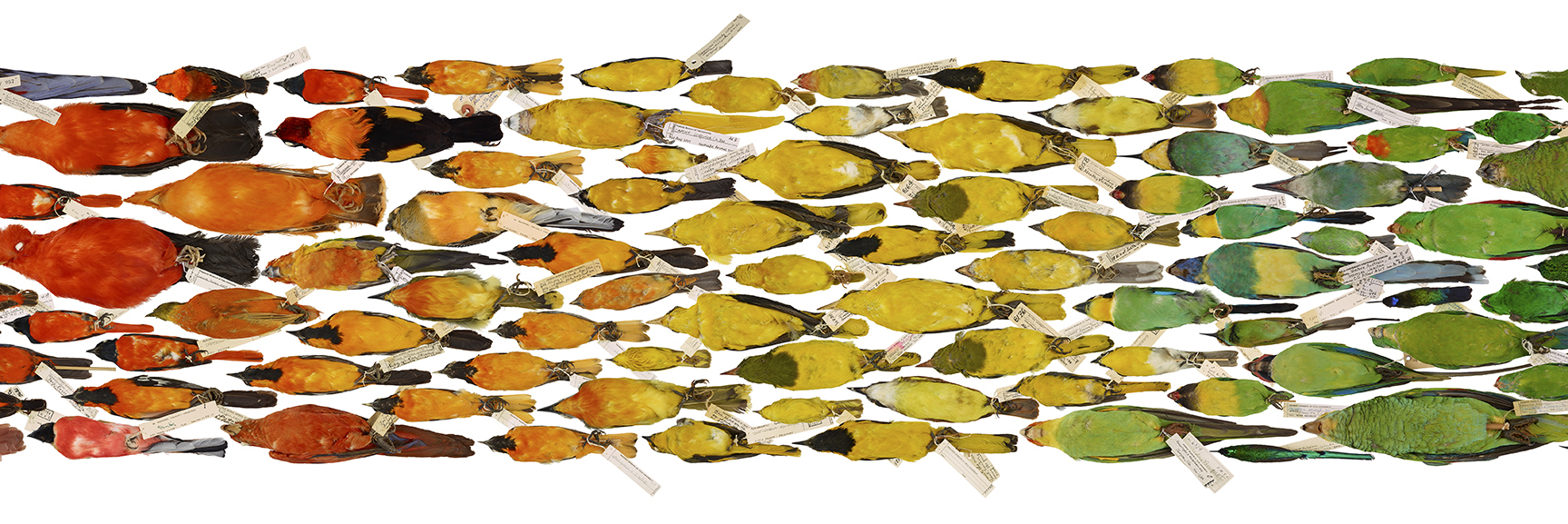

The centerpiece of the show is an installation titled “Bird Spectrum,” in which 222 bird specimens from the Peabody are organized by color. The installation shows, through a rainbow color continuum, that there are no clear lines in nature.

“There is no clear place where red ends and orange begins — we make these fragmentations so we can communicate them, but often forget that nature is so much more than that,” Prosek said. “Divisions we make can become problematic and lead us to different problems when discussing race and gender and identity, when we’re all really part of this same holistic continuum.”

Prosek noted that, in bringing objects from a scientific institution into an art museum, he hopes to highlight that these distinctions are “artificial.” He added that humans tend to intellectualize their artistic expression, but humans’ creative tendencies are similar to those of animals. He said that humans make tools and art, but beavers make dams, and birds make egg drawings.

By showing that humans are not very different from animals, Prosek hopes to highlight his show’s call to conservation. He said that because the planet is “falling apart,” it is an important time to examine why this is happening, and what we can do.

“I think getting people to fall in love with the beauty of nature is a great way of motivating them to protect it,” Prosek said.

Freya Savla | freya.savla@yale.edu