Marlena Raines

January 30, 1969

On a raw, unpleasantly windy afternoon in January, the Beatles performed their final show on the roof of the Apple Corps headquarters in the center of London’s office district. They played a short, 42-minute set until the Metropolitan police shut them down.

It was an undoubtedly strange legacy to leave. The most influential band of the 20th century spontaneously climbed five stories to a nondescript rooftop, performed a very short set to nobody in particular, and then never played together again. That final concert is now the stuff of legend — a miracle birthed amid the tensions of a band that had been growing steadily apart.

After they became successful, their live shows were notoriously inaudible. Legions of fans screamed so intensely that they drowned out the music, leaving both audience and artist unsatisfied. It was more of a circus than a music show, so eventually the Beatles just stopped touring. They retreated into the studio and shed their matching suits, bowl cuts and “She Loves You, Yeah Yeah Yeah”s and grew into something stranger and more substantive. The Beatles became a studio band, a mysterious, ethereal entity more suited to out-of-sight rooftops than large stadiums and arenas. They recorded revolutionary albums like “Sgt. Pepper’s” and the “White Album,” but as they reached the end of the ’60s, they knew they were losing their roots. They came up with a project to halt the tension and turmoil that was threatening to break them up, an “honest” album originally titled “Get Back.” They hired a crew to film the process of recording and rehearsing the album, an intense experience which only heightened tensions already present among the musicians. But the band wanted an appropriate end to the film, and so they decided to perform one more live show — something climactic and spectacular to secure their legacy. Rolling Stone reports that they considered everything from the Sahara desert to the Giza pyramids to a cruise ship to an ancient Roman amphitheater. They imagined playing as the sun came up, with crowds of people streaming towards them to watch the Beatles herald the sunrise. They imagined fantasy after fantasy in a desperate attempt to catalyze unity and regain some semblance of who they were before.

But nothing could be agreed upon, and somehow, they ended up on the top of a roof in the middle of London instead. It was a wild, serendipitous proposition that seemed to spring into existence from nowhere — at least five different people are credited with the idea, and the origin story remains murky to this day. It was cold and slightly rainy, and the band nearly didn’t go through with it. They huddled at the top of the stairs, debating whether or not to play. “George didn’t want to do it, and Ringo started saying he didn’t really see the point,” said film director Michael Lindsay-Hogg. “Then John said, ‘Oh, fuck it — let’s do it.’”

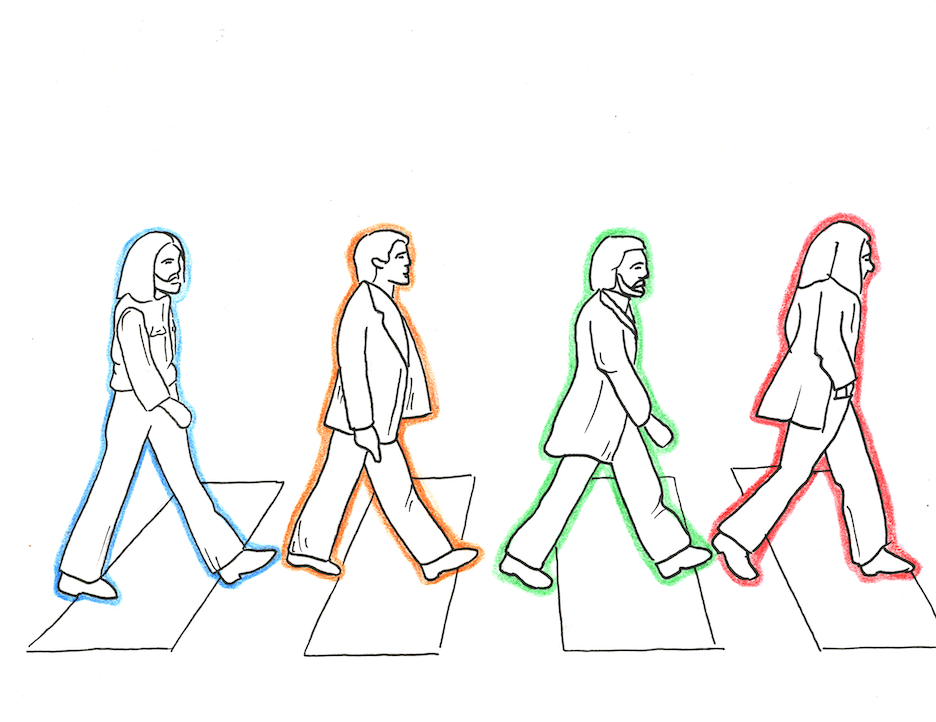

That final performance was more spectacular and mythic than any exotic concert would have been because it was the antithesis of all their other concerts. It wasn’t a carefully planned and prepared affair, but a desperate, spontaneous effort to save something that seemed irreparable. There were no yelling fans or massive crowds, but only those who happened to wander past. For the first time since they were young, the Beatles played to nobody and everybody: passersby on the street, cops that told them to be quieter, workers passing the foot of the building on their lunch breaks. The set list was strange and unexpected because the Beatles were ultimately playing for themselves. They sang together like they hadn’t in years, performing songs they’d written when they were young. For a brief moment, all the turbulence faded away, and they became again what they always were at their core: four remarkably talented kids who grew up playing together, having a good time.

They paired the early songs with later ones such as “Don’t Let Me Down,” recorded during the “Get Back” project sessions. “I’m in love for the first time,” they sang, seeming to reference the exuberance of their younger years. “Don’t you know it’s gonna last. It’s a love that lasts forever, it’s a love that has no past.” And just like that, almost accidentally, they achieved their original project: unity. Older and racked with tension, they sang “One after 909,” one of the first songs they’d written. “I’m in love for the first time.” It had been two years, but they played together just as seamlessly as they did before. “Don’t you know it’s gonna last.” They linked their earlier selves and their later selves, creating a unity and an artistic culmination that was utterly timeless. “It’s a love that lasts forever, it’s a love that has no past.”

“Don’t let me down.” It was a supplication to themselves, an urgent request to never again forget where they had started. They didn’t need a massive crowd and a spectacle in the Sahara desert to secure their legacy because that wasn’t really who they were at their core. Ultimately, the band was about the four of them growing up together. They rediscovered their roots on the rooftop that day, and they were young again.

And so the incredible magic of the final concert is that it made them timeless. Their later years are inextricably linked with their younger ones. The tensions and estrangements that plagued them are just a blip in an endless cycle of growing up, getting older and discovering youth again. The decision to play on the roof of their office building is both a weary, last-ditch effort to save a failing band, and a mischievous, youthful endeavor. “One After 909” leads effortlessly into “Don’t Let Me Down,” and vice versa.

The “Get Back” project was released as “Let it Be” in 1970. By the time the public could watch the rooftop concert, the Beatles had broken up. But an aura of timelessness surrounds them still, and their final performance has become our cultural folklore. Even now, so many years later, I walk through London, and I can almost feel them hovering above me. I can’t help but imagine that one day I will turn a corner and hear them, playing just out of sight amongst the rooftops.

Sophie Pollack | sophie.pollack@yale.edu