Alex Taranto

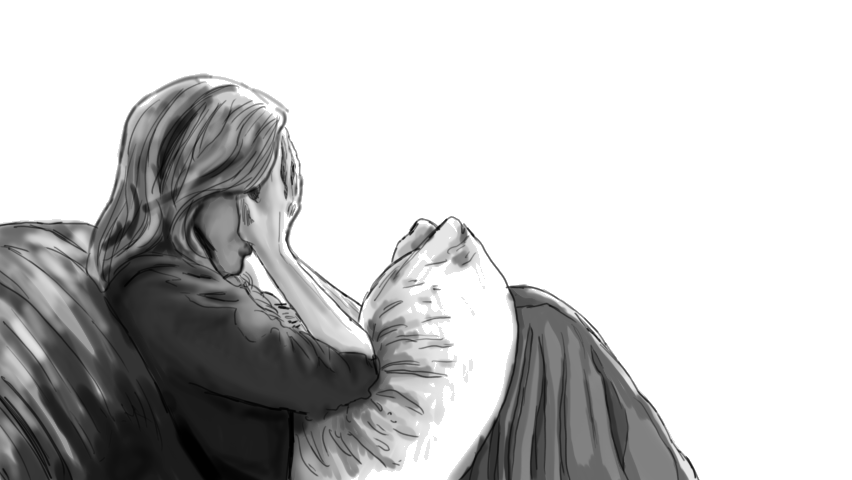

Relationships at Yale are hard, and breakups, whether romantic, platonic or somewhere in between, are even harder. But breakups are both ugly and beautiful for the same reason: they remind us that we’re human and nothing more than human — even if Yale would like us to believe otherwise.

The first thing a breakup breaks is some crystallized version of the future. Crystallization, coined by the 19th-century writer Stendhal, is what occurs when your mind smooths out an object of desire’s imperfections, rendering them a shiny, perfect crystal. We do it all the time.

The future is a fiction. It exists only in our heads. But that construction of the future, what it might hold, who might be in it, shapes how you go about today. You might imagine yourself a decade or two from now settled down or maybe even married. A breakup dissolves that future. You might imagine yourself in a C-suite or on C-span or MSNBC, and a rejection letter shatters that crystal.

But those crystals, the ones that contain decades of perfection, are especially fragile. In your college relationship, you probably didn’t imagine yourself one day getting married, but you definitely imagined yourself at lunch together or in the library. And when you imagined a shoulder to cry on, it was theirs. A breakup shatters that crystal. Then, you have to walk over the shards. Actually, you have to run.

Life at Yale moves fast. We live it 12 weeks at a time. We immerse ourselves in new languages, new topics, new problems to solve and, for the most part, we make it through.

But ideas move faster than feelings, especially when some of the best scholars in the world are teaching us. At Yale, we have access to centuries of aggregated knowledge condensed into 75-minute portions for us to digest. You don’t have to retrace Darwin’s voyage around the globe to understand the basics of natural selection — you have a professor instead. But you might need a ship and a gap year or two to understand the emotional weight of such a journey. That’s the thing about feelings — you have to feel them yourself.

Even if we’re super smart and super ambitious, we’re not superhuman. And so, a semester or two after a breakup, we find ourselves thinking: “I’ve done and learned so much, I’ve read and written tomes upon tomes — so why can’t I get over the person I once loved?”

We worship the superhuman. The CEO that wakes up at 3:30 a.m., the musician that plays until their fingers bleed, the student that studies until they pass out in their open textbook, people who seem to supersede their human limitations to do something great.

But exceptionality is not an all-encompassing ideal. And while Yale is a place built on exceptionality, it doesn’t have to permeate every facet of our lives.

Even if we are to aspire to insane work ethics and undying commitment to greater causes, we ought to make one of those causes our relationships — and, from time to time, understanding why they don’t work out.

After all, Yale is all about relationships. It’s not what you know, it’s who you know, right?

But treating relationships like a fifth class, as we so often do, is another misstep. Relationships, by nature, defy the input-output correlation we structure our lives around. Upon a breakup, all that time and effort you put in amounts to nothing.

But only if you let it.

Broken relationships suck. They always suck, no matter who or where or what you are. Admittedly, it feels a little infantile writing this. But if taking your feelings seriously is infantile, then get me a binky and tuck me in.

Breakups of any kind reveal a deep truth about us: we feel more than we understand, and far more than we can ever hope to put into words. But it’s still worth trying.

Just as we hide behind big words when we have no clue what we’re talking about, we let our big school and our big futures do our thinking for us when we have no idea what we want. When we submit to the idea that “relationships at Yale are impossible” because of the atomizing academic and professional forces pulling us in every which direction, we let our institutions do our thinking for us. And while they can think for us, they can’t feel for us. We have to do that ourselves.

Big schools, big companies and big words don’t make the small things hurt any less. For as long as we uphold the fiction that they do, we deny ourselves the beauty and joy and complexity and pain inherent to being a human.

It’s not what you know, it’s not who you know, it’s how well you know them and, really, how well you know yourself.

Our university’s president literally made his name arguing that emotions are complex and that emotional intelligence is important. But I’m not going to argue that emotional intelligence is important because it’s one of the key traits of CEOs, or that any of what I’m recommending is going to make you more successful than you already are. Give energy and dignity to your relationships. They’re inherently valuable. In a place full of means, treat them as an end.

Every book we read at Yale is available in a public library. Every equation we learn is on Wikipedia. So why be here at all? Somewhere in the rationale for this place is the idea that if you take a bunch of smart, passionate people and put them all in the same group of neo-gothic buildings, you get something greater than the sum of its parts.

We’re here to form relationships. Let’s care about them — especially when they don’t work out.

ERIC KREBS is a junior in Jonathan Edwards College. His column runs on alternate Thursdays. Contact him at eric.krebs@yale.edu .