Anasthasia Shilov

The mugginess of the desert day temperature has evaporated, replaced by the cool night air. Aviv and I are sitting on a bench in a nearby park, with our eyebrows creased. There’s suspense in the air.

He breaks the silence, asking, “So who are they?” I’m quiet for a minute, mentally reviewing a week of walks to the institute, cooking duties, ice-breakers, hiking buddies, bar adventures, and notes passed during lectures. Another week of living in a foreign country, without my family, alone. I blink once, and then I start listing my friends, one at a time. I rank them, ordering them in a hierarchy of closeness.

This park-bench, late-night conversation has become routine, a staple of the first few months of my gap year. Aviv and I often escape our dorm building and the adrenaline of 60 teenagers all living and laughing and being emotional together. We run to the quiet solitude of an empty park bench two blocks away.

And while there, we try to reorder the messiness of our social lives. We attempt to insert logic into the absolute chaos of meeting 59 new people and then spending every second of a year with them. Though friendships spring up, disappear and swing dramatically back and forth, Aviv and I convince ourselves that our relationships will eventually settle down to a clear, well-understood reality. And until that point, stability exists in our weekly review.

About a quarter of the way into my gap year, though, I felt more alone than ever before. I called my mom, crying on the phone. “I have no idea who my closest friends are,” I explained to her, wailing. “I don’t have one close-knit group.”

“Why do you need just one group?” she replied.

I rolled my eyes. In the comfort of middle age, she’d forgotten what it means to be a teenager. I hung up, feeling misunderstood.

And that resifting of friend groups happened again and again. Each time, as the ground beneath my feet shook and restructured itself, I felt myself free-falling. I clawed, desperate to grab onto a social foundation. With each new friend group, I promised myself, “This is the one. These are the people I want to spend all of my time with.”

I had a month left on my gap year when I realized I was lying to myself. There was no friend group that I wanted to spend all of my time with. There were the nature-lovers who gathered for midnight chats on the roof under the stars. The artists who scrutinized museum pieces and argued with me about their meaning. The rowdy, athletic guys who were secretly math nerds. The politically-involved leaders who ditched activities to hear local speakers. The cinephiles who scoured the city for foreign film showings.

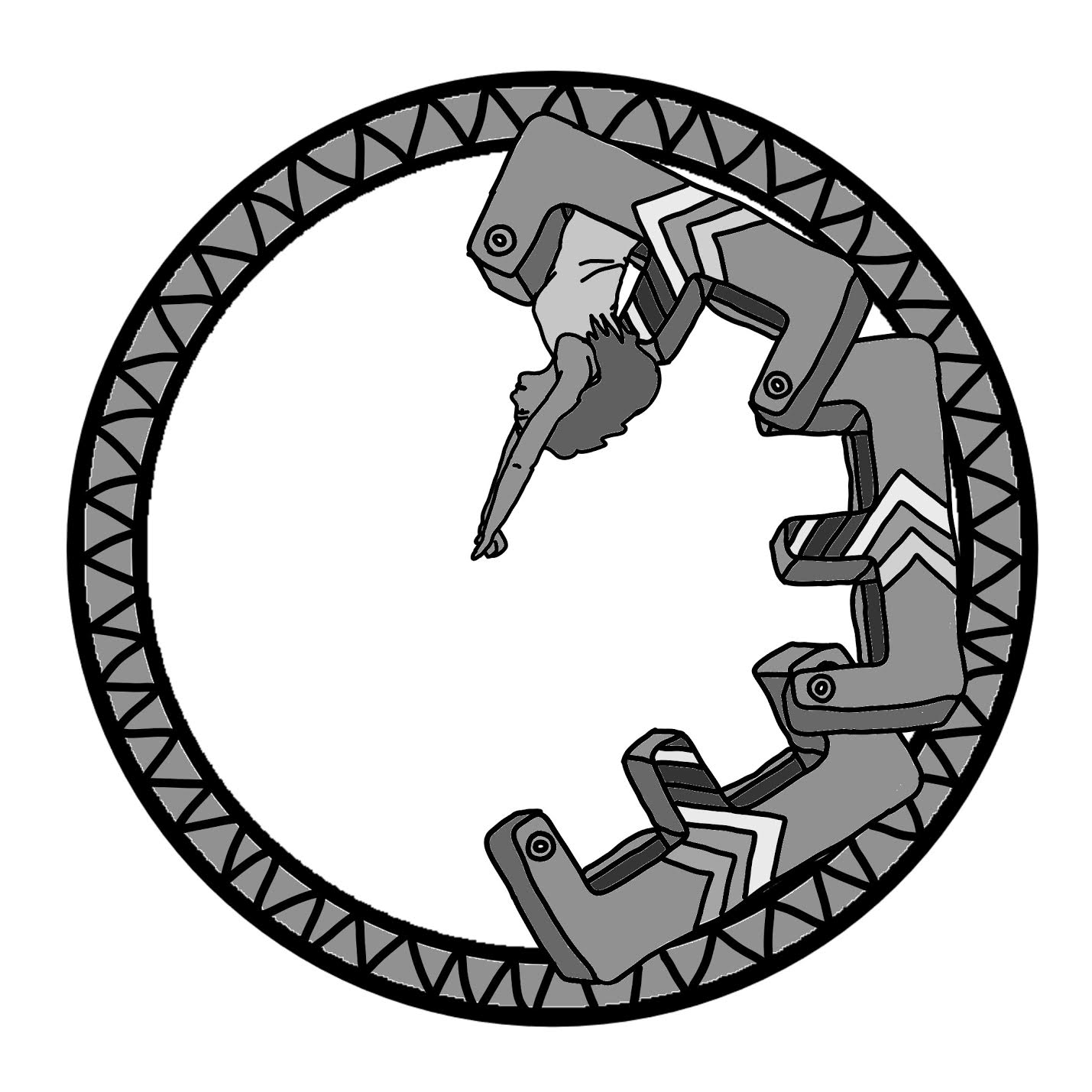

I loved each of these groups and the people within them. And once I was able to admit that my desire to pick just one group was a doomed quest from the start, I was suddenly able to see how normal I was in not belonging to only one group. These groups were overlapping circles, scrawls of people sloppily joining together, rather than perfect puzzle pieces.

And I also began to appreciate that my friendships would continue to skyrocket and trail off, to bounce up and down, indefinitely. There was no steady state that I was slowly heading towards. There was no saturation point where I suddenly had all of my close friends and wouldn’t make any more and there was no guarantee that I wouldn’t drift away from someone.

I finally understood that all of those escapes to the park bench — the need to establish social stillness — was just an opportunity to feed our anxious energy. To live in the here and now is to exist riding the curves of many circles, with all of their dizziness included.

Ayelet Kalfus | ayelet.kalfus@yale.edu