Judith McCartney

The power of solidarity rang clear at the annual APS Conference for Undergraduate Women in Physics, or CUWiP, this past weekend on Science Hill.

The network of three-day conferences brought over 200 women in STEM together to connect, educate and lean on each other as they navigate the world of physics. It also addressed the well-documented retention problem with women in the field and encouraged underrepresented minorities to enter STEM.

“Finding the community of people that you feel comfortable with, who you look like, who you identify with is vital because being able to not be a perfect student for a moment and talk about your struggles and plans for your career is so important,” said India Bhalla-Ladd ’21, a member of the CUWiP organizing committee and current physics undergraduate student. “You need peers that are dealing with all the same questions.”

According to most recent figures from the American Institute of Physics, women only earn 21 percent of physics bachelor’s degrees and 20 percent of physics doctorates. Over the past decade, these figures have resolutely remained unchanged, according to the institute, despite the increasing number of women enrolling in physics graduate programs.

Disparities remain when women enter academia: Around 13 percent of last authors of physics research papers were women, with last author usually reflecting seniority. Researchers have attributed this lack of representation to several factors. Often referred to as the “leaky pipeline,” some have argued that the high attrition rate of women in STEM fields affects women at all stages of development and education, particularly early professional life and undergraduate education. It suggested that a lack of educational, mentorship opportunities and visibility of female leaders can all lead to an undergraduate degree in physics being a difficult experience.

“More effort needs to be made to hire more women, especially of color, into positions of power and leadership,” Bhalla-Ladd said.

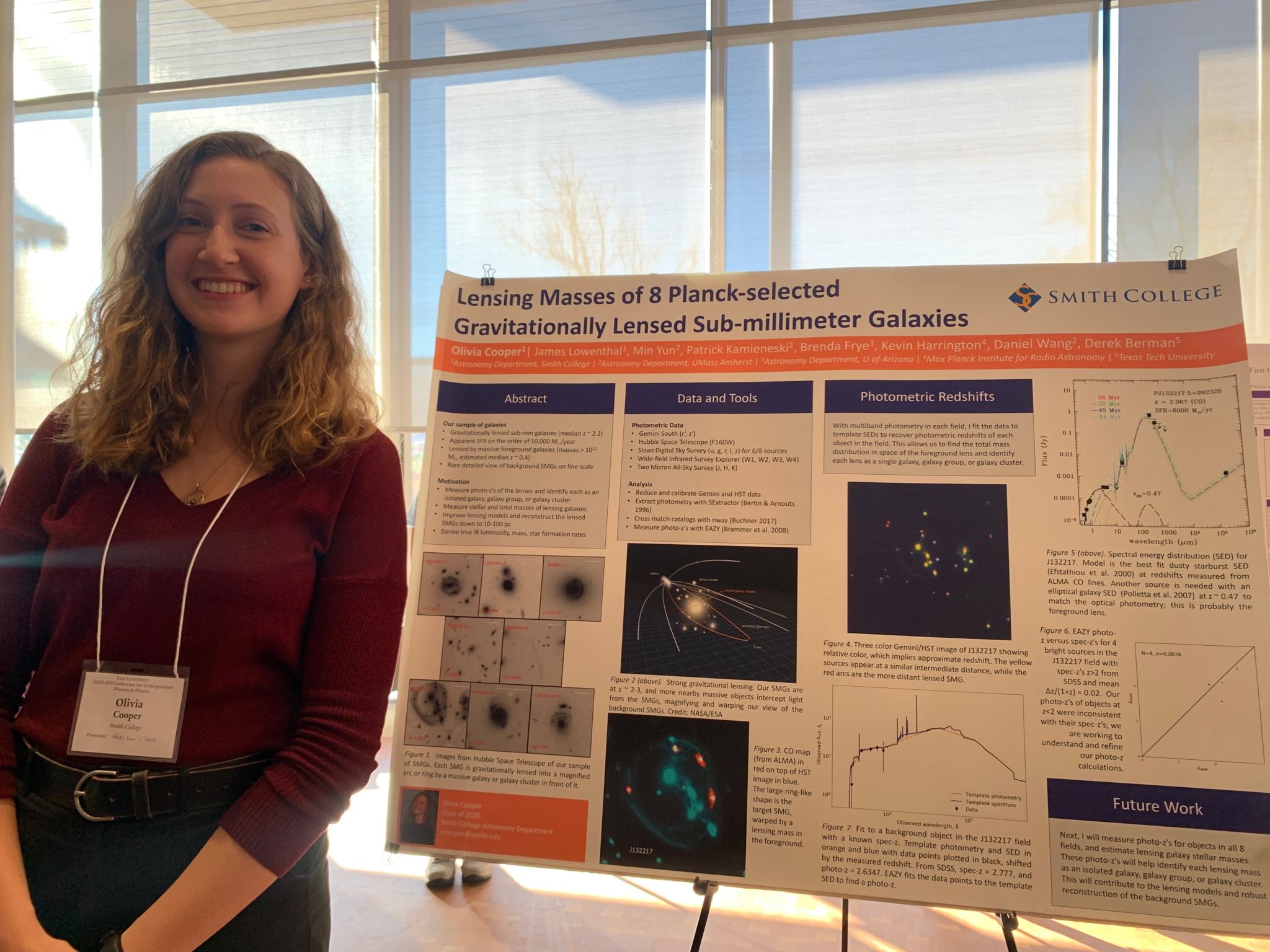

Delegates at the conference proudly presented research posters at the Yale Science Building this weekend. Women in attendance — both first-time and repeat attendees — were keen to chat about what brought them to CUWiP.

For Olivia Cooper, a Smith College undergraduate who attended the conference for the first time last weekend, attending her all-women college has given her “more confidence to meet a male-dominated workforce.”

Chloe Thorburn, an undergraduate from Wesleyan University and fourth-time CUWiP attendee, reflected on the first year she attended CUWiP.

“I looked at all the amazing posters and thought about how I would ever reach that level,” Thorburn said. Now, Thorburn said that presenting her own work highlights the importance of events like CUWiP that promote female representation in a predominantly male field.

CUWiP also provided a unique wopportunity to connect with some future employers in a relaxed environment. Fireside chats and workshops made up the bulk of the conference, providing ample opportunity for women to introduce themselves to some of the leading female figures in STEM.

The archetypal image of the “lone genius in the basement, solving all of the world’s problems” as Bhalla-Ladd put it, is no longer recognized. Rather, the scientific community emphasizes collaboration, and Bhalla-Ladd described the conference as a good opportunity to have fun and get to know the women who could become future collaborators and colleagues.

“CUWiP is a hub of advice, mentors and possible connections … with the hope to expand the scope of possibilities that people think are available to them,” Bhalla-Ladd said.

CUWiP was created in 2006 by a group of women physicists from the University of South California in 2006. It now connects woman physicists nationwide.

Judith McCartney | judith.mccartney@yale.edu