Marlena Raines

The Roaring ’20s: flappers, bootleggers, and activists all finding their way through a labyrinth of political reform and increased urbanization. The people of the 1920s were, indisputably, witnesses of intense and fascinating years.

The beginning of 2020 puts the Jazz Age in a new light, letting us look back on the decade not only with the perspective of a history student, but also with the knowledge that we are, crazily enough, already a century removed from it.

The progressive and unrestricted energy of the ’20s pervaded nearly all corners of America, making these years decisive for many people, including — of course — the students of Yale University.

It’s difficult to picture what Yale was like so many years back, but the ringing in of 2020 provides the perfect opportunity to reflect on Yale’s history and imagine the life of Yalies in the 1920s.

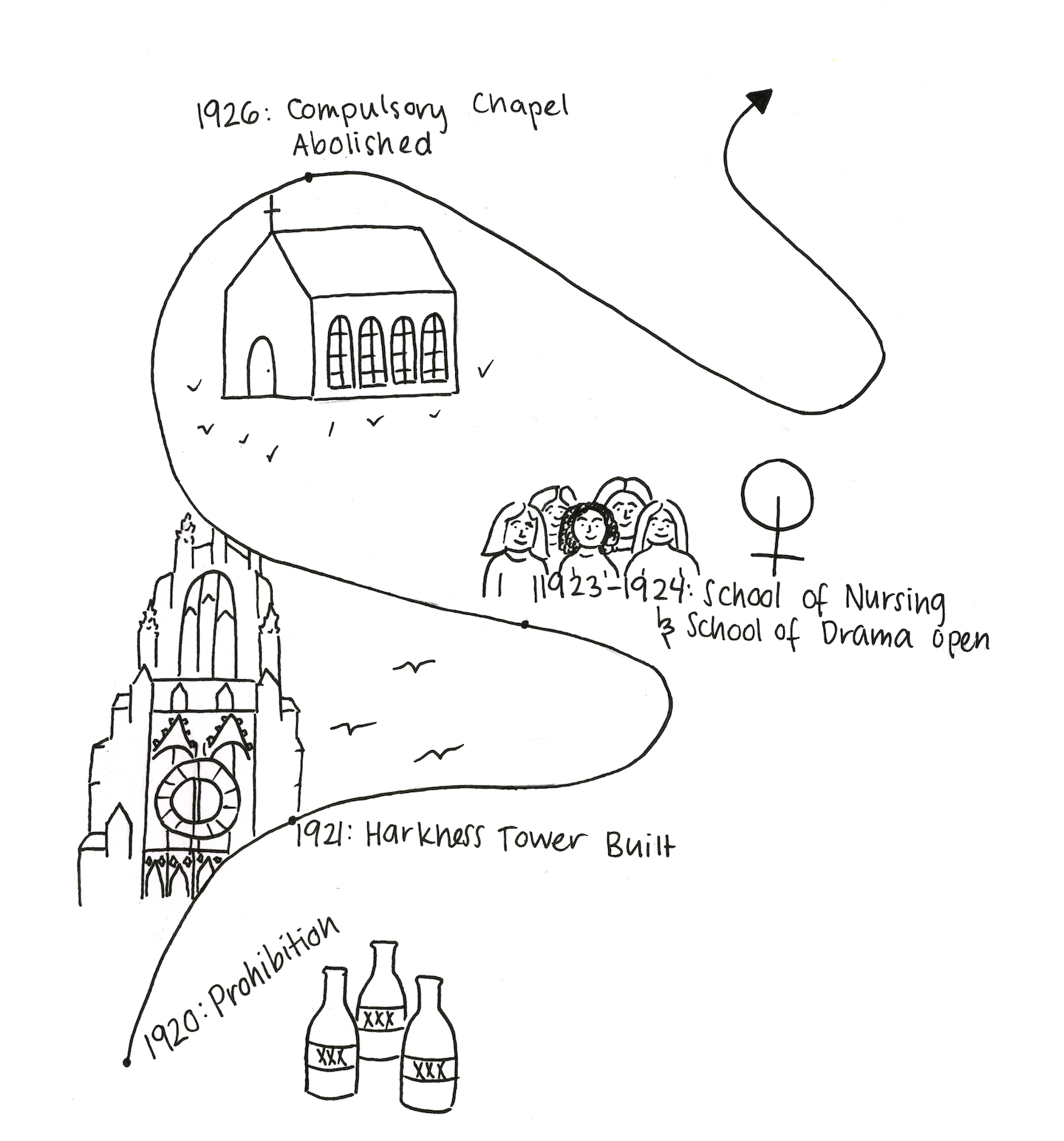

The decade began with Prohibition, something that Connecticut largely opposed. The state’s rejection of the 18th Amendment was to no avail; in their first edition of the decade, the Yale Daily News reported on the Supreme Court case that upheld the constitutionality of Prohibition. This did not stop Connecticut from rebelling against the system, however. According to the New England Historical Society, it was estimated that New Haven was home to at least 400 speakeasies during the 1920s.

On campus, the social scene for Yalies could be distinguished in a few ways. For one, Yale hosted an annual winter dance called the Junior Promenade. A Yale Daily News article reports that this dance was very popular in the early 1900s; it was a three-day event, the social highlight of the year, and a guarantee that women would be visiting the otherwise all-male campus. The Prom was an esteemed tradition, yet the New York Times reported that the event was neither widely supported nor well attended in later years, leading to its discontinuation in the late 1900s.

Also, a common pastime for students was to toss around pie tins to one other on campus. Most pie tins belonged to Bridgeport’s Frisbie Pie Company. Legend claims that this marked the true invention of the “Frisbee,” long before it was patented and commercialized in the ’50s.

Yale students of the ’20s had their routines just like we do now. But despite certain constants, this was a time of great change. To live at Yale during the ’20s was to witness several turning points in history. While the undergraduate school was not yet coeducational, women were able to attend the newly opened the Yale School of Nursing in 1923 and School of Drama in 1924.

Yale also experienced a secular shift during the ’20s. The social unrest and attacks against Yale’s Christian ties were part of a progressive movement so drastic that the Harvard Crimson reported on it in 1923. The article noted that Yale students were becoming increasingly unhappy with Yale’s curriculum and obligatory attendance for all students at chapel services. Yalies advocated for the greater presence of a student government and formulated arguments against the compulsory chapel. At first their efforts were fruitless, but 1926 marked a great religious pivot for Yale. After 225 years of mandatory attendance for worship either in Woolsey Hall or Battell Chapel, Yale finally eliminated this obligation.

The end of mandatory chapel may be viewed today as a rational and natural event, but Yale’s students of the 1920s were witnessing a highly controversial and contested subject. Ultimately, we can now appreciate this decade as a key turning point for social change.

Just like with student activism, Yale wouldn’t be Yale without undergoing constant construction and renovation, and this was no different in the 1920s. With significant donations from the Harkness family and John W. Sterling, Yale was able to complete the construction of Harkness Tower in 1921 and begin the construction of Sterling Memorial Library in the late ’20s. Other projects of the decade included a new art gallery as well as laying the groundwork for the residential college system, which was officially established in the early ’30s. These projects served Yale well; resultant job opportunities helped the community combat the Great Depression.

With minimal technology, a much smaller student body, and an endowment one-thousandth of its current size (still $30 million before inflation), Yale of the 1920s seems almost unrecognizable. My view from Bingham Hall, my morning walks to class, and my day to day activities have all become so familiar and comfortable that I can’t even imagine being at Yale during any other time period. But Yale back then was steering itself on a familiar path toward reform and success; it’s one that we are still navigating in 2020.

Jessica Romero | j.romero@yale.edu