Sophie Henry

On Howe Street, at night, the cars idle in groups at every corner, yielding to the walkers because they understand that the night belongs to them. People lounge outside of restaurants with their lovers and friends, taking long drags from tall glass hookah pipes. The embers burn red in the plates, and if you walk by too quickly, you’ll mistake the purring of the bubbling water for the sound of a dog growling softly at your heels. At one table, a man and a woman that seem to have been married for years trade a hookah hose back and forth. At the table right next to them, a middle-aged man who just got off of work, still in his business suit, smokes his pipe all by himself and stares off into the street.

Someone calls, “Meet me at home!” out into the street. There is no response.

“COORS LIGHT” and “KINGFISHER PREMIUM LAGER” flash in the windows of a restaurant fashioned after an old diner, its rounded facade clothed in an aluminum skirt all the way around.

The streets smell like curry and sometimes, because of the way people live in them, feel like a giant house. Take the one girl standing outside her house’s steps, for example. She’s talking to her friend who’s still inside. Her hair is wet, like she stepped straight from the shower onto the street, and her voice carries all the security of being within the walls of her home. As I walk further down Howe Street, two people stand talking on a corner even though the lights have changed. They’re about 30, a man and a woman, and obviously flirting with each other. The man is tall and thin and bends over to listen to the woman speaking. “Can’t breathe, must exit!” she says, pretending to gasp for air. She is imitating someone, and they burst out laughing at the same time that the accumulated cars rev their engines and cross the intersection. Behind me walks another couple, a pair of Yale students out to take the night air and air their grievances.

“I’m so afraid we’re gonna get equine encephalitis!” I hear the woman say.

“Why, because we’re out right now?” the man asks.

“Yeah, I’m so worried.”

“Wow. That’s not something I’m super concerned about actually,” he says.

A loaded silence follows and walks me on down the street.

Two men walk towards me, talking to each other and looking into each other’s eyes. Though their arms swing in perfect sync, they don’t hold hands.

All of this — the hand-holding, the sitting back and smoking hookah, the talking comfortably out in the street — is the product of people living in a city that they know and that they have grown in over time. They are the consequences of a city that develops organically and authentically, not those of a city that has had structure imposed on it like veneers over natural teeth. People who have truly lived in and understand a city balk at the idea of their city being so contorted, and for good reason: The living, breathing entity that has shaped them as much as they have shaped it has been forced to be something it is not. In classic aesthetic dentist fashion, Yale has been attempting (and succeeding in many instances) to force veneers down over New Haven’s teeth — sometimes crooked, sometimes stained, but genuine teeth — for decades.

Only yesterday I saw a Facebook post declaring Yale the most dangerous college campus in Connecticut, and one of the most dangerous in the country. The post was just the most recent in an onslaught of criticism and largely unfounded fear of New Haven and an example of the kind of news that dissuades students from applying to and attending Yale. Or so Yale fears. Largely in an attempt to mediate the effects of such reports, Yale has steadily bought up the land surrounding its campus and renovated its buildings. The so-called “Shops at Yale”— FatFace, Urban Outfitters, Apple, Barbour, Derek Simpson Goldsmith, Gant, J.Crew, L.L. Bean, Patagonia, Sneaker Junkies, Lululemon, Blue Mercury and more — are an emblem of this transition towards the polished and global.

It is not just New Haven that is swapping out its mom-and-pop stores for the likes of Lululemon and Urban Outfitters. In this city’s case, Yale has played a vital role in the process. New Haven is coming to look more and more like every other city in the world and becoming less and less habitable (for its permanent inhabitants) as it does. Most days, these stores are empty. Maybe there is one lonely Yale student in one shop, looking to spend their monthly allowance or something, but chances are, not. The shops are invariably very high-end, expensive stores, and New Haven has a notoriously low average income. There would seem to be a mismatch here. And yet it was these stores that Yale chose to subsidize to come open as part of its shiny “Shops at Yale.”

It stands to reason then that these shops would be empty. They are veneers that hide what is unique and genuine about a city and, worse yet, essentially stop its inhabitants from being able to inhabit it.

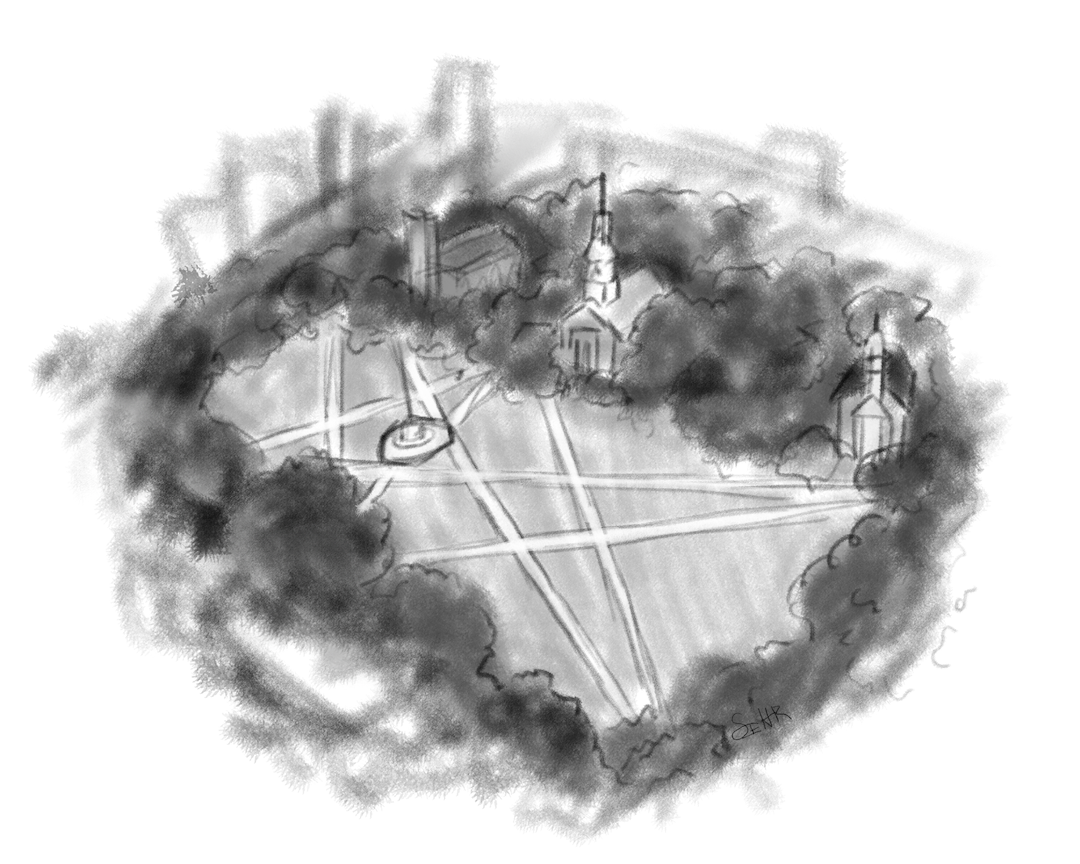

In 1638, New Haven was founded, a perfect nine squares arranged in a grid. The English Puritans chose this “nine-square plan” because it mirrored the encampment of the Israelites. The Puritans simply could not resist the symbolic appeal. They too were religious exiles rebelling against the misguided status quo, out to spread the true word of God. At the center of the nine squares, they built the New Haven Green, and it became a graveyard. The bodies of the wealthy were buried in marked, individual graves, and the bodies of everyone else were piled on top of one another in large pits. In the 19th century, they refashioned this graveyard into a social space with three main churches spreading across the grass and crisscrossing walking trails between them. Though Yale owns almost all of the land around the Green, the Green itself feels nothing like Yale. It does not feel polished like the University campus does. Though people sprawl against trees and across benches and lie in content puddles on the grass just like on campus, there’s something different here: the feeling of disorganized reality, the ugly underside of what is real. This, New Haven’s heart, feels Yale looking down on it from its high-up windows in Harkness Tower and through the grandeur of Phelps Gate. To lie down in the grass in the Green as someone from New Haven is to feel the history of your city below you, and above you have the entity that is paving your city over with white.

The New Haven Green smells like marijuana, and the glowing butts of joints pulse red in the night. Down on Howe Street, couples smoke hookah by the bowl. People hold hands and talk about Eastern equine encephalitis all up and down the street. People lean against each other comfortably sitting on benches and lay across each other on the damp grass. FatFace opens its doors for the day, and no one walks in, the buzzing of the lighting audible over the sound of nothing. Urban Outfitters puts up its newest crop top in the display window and affixes to it its triple-digit price tag. A little boy stops following his father because he suddenly feels the distinct sensation of something glued to his sole. He picks up his right shoe, and sure enough, he finds an orange maple leaf.

Annie Radillo | annie.radillo@yale.edu