Native Voices, Now In Limbo

The Native Northeast Research Collaborative helped Native American communities reconnect with their history. Yale’s decision not to renew its funding could change that.

Paul Grant-Costa GRD ’02 knew that he would one day have to move out of the Yale Divinity School — the headquarters of the Native Northeast Research Collaborative, a project that aims to preserve historical records of Indigenous communities in New England.

The grants that had sustained the project were running out. The last day of funding would be Sept. 30, 2019. Then, he said, he figured he would have to move the project off campus and scrounge up the money or institutional support necessary to keep it alive — and its documents easily accessible for all.

In July, Grant-Costa and his colleagues had made a plea for more support from Yale. But they knew it was a longshot. Armed with roughly 30 letters of support for the project from scholars, Indigenous tribes members and Yale staff, the NNRC’s faculty advocates at Yale — Tisa Wenger and Claire Bowern — met with University President Peter Salovey with a request for about $250,000. That would cover the project’s expenses — including server fees, transcription help and consulting from Indigenous groups — for a full year. In that time, the faculty advocates told the administrators, the NNRC would look for outside grants, too.

“We knew that was a big ask to make at the very last minute,” Wenger recalled.

Yale ultimately declined the request. The project does not “directly support” members of the Yale community, University Provost Benjamin Polak said in an email to the News, adding that Yale’s administration generally doesn’t provide funding directly to individual projects.

By the time Grant-Costa said he found out about the University’s decision, it was well into September — about a week before the grant’s expiration. He had to move his project, and fast.

“It was a little bit of a shock, I would say. But it wasn’t unexpected,” he explained.

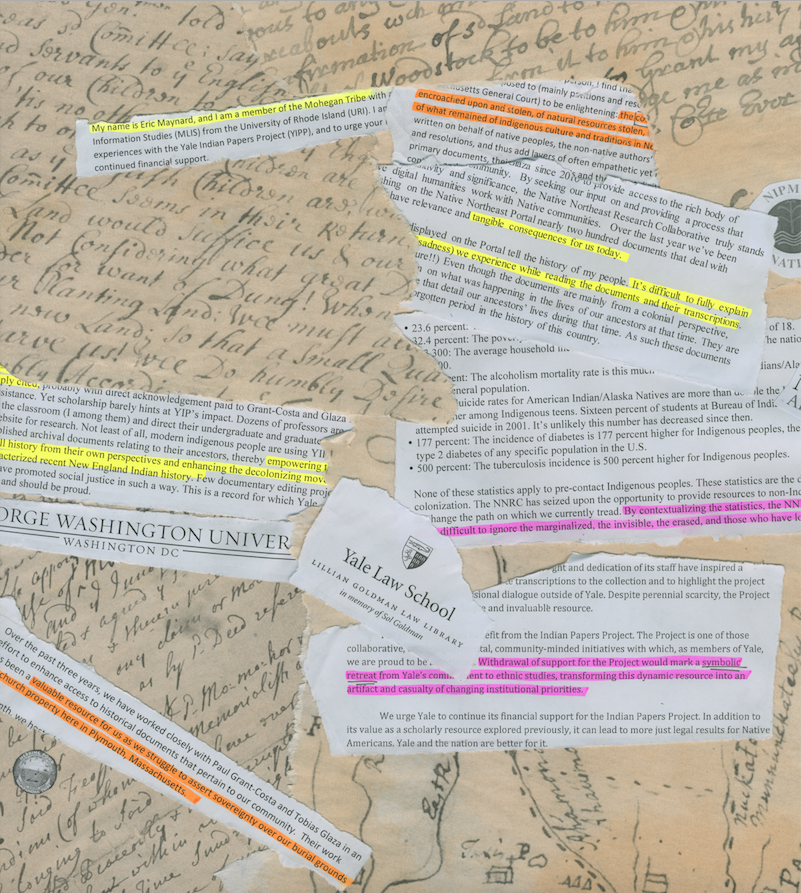

The Native Northeast Research Collaborative — formerly called the Yale Indian Papers Project — serves as one of the few bridges between elite institutions including those in the Ivy League and the Indigenous groups whose land they occupy. With the help of tribal representatives and student employees, the project has digitized wide swaths of colonial-era letters, records and contracts that involve Native people. Much of it documents their persecution and their pain through a settler lens. But between the lines of steady cursive are also stories of tribal heritage.

Documents found on the NNRC’s online portal have a combination of some or all of several resources: a high-detail scan, a scholar’s transcription with words exactly as they appear on the original document, an annotated transcription that’s easier to read and a brief summary. Visitors can browse through the collection and sort by community, subject matter and keywords, among other criteria.

Teachers and professors use the project to show students a more authentic version of early American history. Many tribal leaders use the database to connect to their ancestors and to trace their communities’ pasts. Without funding, however, the project has been put on hiatus — or, at least uploaded at a much slower rate — and the fate of the Collaborative remains in limbo until a source of cash is found.

“An Act of Erasure”

While he was a graduate student in Yale’s American Studies department, Grant-Costa began what would become the NNRC as an effort to gather primary source documents that would have otherwise remained scattered across the Northeast. Since its inception roughly 20 years ago, the project has amassed documents from places that are often hard-to-reach for the average historian or student. Many Native colonial-era documents are held on their land. For someone writing a research paper, Grant-Costa said, traveling long lengths to access these letters can often be prohibitive.

“I proposed this project as a way of showing that Yale is committed to Native people,” he added.

Katherine Sebastian Dring, the chairwoman of the Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation, knows what it’s like to hunt for research materials. With the help of Grant-Costa and Glaza, Dring and others scrounged up thousands of documents relating to her nation to apply for federal recognition — a step that would grant more economic opportunity for the Native tribe. But once the nation was recognized, Dring said that she wanted to make her people’s roughly 60,000-document collection more accessible to the public. So she turned to the NNRC.

“Most people in the United States are not aware of [our history],” she said. “These are important historical documents that are really the fabric of early colonial history in the United States.

Histories other than those of Native Americans are currently being documented at Yale. Established in 1954, the Papers of Benjamin Franklin is one such project which seeks to digitize the writings and papers of Franklin; a similar project founded in 2003 aims to accomplish the same for the works of Jonathan Edwards. Both projects are supported by Yale and the National Endowment for the Humanities, along with scores of outside funds, grants and donors. In contrast, while the NNRC has also received grants from Yale and the NEH, its list of outside contributors is less replete.

As of Thursday, the NNRC has digitized several dozens of letters, petitions and manuscripts about Dring’s tribe, complete with annotated transcriptions and links to other related texts.

Just like the founding fathers’ multi-volume tomes of correspondence, Dring said that the Collaborative’s work adds an informative layer to early colonial history through which knowledge can be increased. Having the documents, she said, can also spark discussions among members of her nation.

“Any time you can have those conversations and have a document, it can actually be something that we can have a talking circle” with the elders about, she said. “Any time you can go back and bring [that history] forward, that’s increasing your knowledge and your truth and being able to express it.”

Dring, like others, wrote a letter to Salovey ahead of his meeting with the NNRC directors in July. She expressed support for the project and its mission, and highlighted the in-person sessions the NNRC held with her tribe to discuss the documents and their historical significance.

Dring did not write alone. Scholars and tribal representatives penned similar letters to the University president.

Elisabeth Nevins ’97, the Director of Education and Exhibitions at the Bostonian Society, wrote to Salovey in April saying that she used the project two summers ago in a teacher training workshop on 1600s New England history. Evaluations from the workshop’s 72 participants showed that the NNRC’s collection was “extremely valuable,” she wrote. And at a time when decolonizing museum collections is of prime importance, she added, the two NNRC directors, Grant-Costa and Glaza, had already been doing such work for over 15 years.

In an interview with the News, Nevins expressed disappointment over Yale’s decision to decline funding the project — especially when other digital humanities projects such as the Ben Franklin Papers continue to partially operate on Yale’s dime.

“This is a documentation of cultural genocide and we want to make reparations to these communities that we continually marginalize and erase,” Nevins said. “This is an act of erasure by not committing to keeping [it]. As a Yale grad, it’s really devastating to me to see how the University is privileging the white male colonial settler viewpoint.”

When asked about Yale’s response to such criticisms, University spokesperson Karen Peart did not directly answer the question. Instead, Peart noted the several ways that the NNRC benefits the Yale community while also referring to Polak’s original email. Yale administrators added that while they recognize the importance of funding the NNRC, managing the University’s budget requires making difficult choices.

At Yale and beyond, the project also brought considerable benefits to classrooms, according to several of the letters’ authors. George Washington University Native American History professor David Silverman said he uses images of NNRC documents to expose students to the layers of scholarly interpretation that can come with reading colonial-era handwriting. Unlike transcriptions found in books, he said, seeing the actual letters can reveal clues about who wrote them and how they were written. And the tight, faded cursive that his students try to decipher helps them mimic what professional historians do.

According to Silverman, the act of transcribing such documents requires a mountainous amount of effort. On top of the “arcane script” of the letters that is unintelligible to most modern readers, many of the Europeans who wrote these documents struggled with Indigenous names.

“Making such documents accessible to modern readers requires more than just rendering early modern handwriting into typescript,” he wrote in his letter to Salovey. “It requires expert editorial guidance.”

When Silverman — who is on the advisory board for the NNRC — wrote his letter to Salovey, he hoped his plea for funding would make an impact. If the project did not have to stay in New England, he said, he would be “going to bat for it like gangbusters for [his] own institution” in D.C.

But after hearing that Yale would not fund the program, he said that the University “[pulled] a rug out from under it … for no compelling reason.”

In an email to the News, Yale Law School Associate Law Librarian for Research Services Michael VanderHeijden said he recognizes the impact the NNRC has made on the students he advises. The project goes beyond the expected duties of a digital humanities project by bringing in Native perspectives and context to the documents and by making them accessible to a broader audience — not just a set of scholars, he said.

“Speaking as a librarian, it’s not often that you come across such an ambitious project,” he added. “It’s a resource that does the usual things (transcription, digital access, etc.) but seeks to do the right by historically marginalized communities.

Even though he can understand why the University administration declined funding the project — “I respect the decision and am thankful that’s not my job!” he wrote — VanderHeijden said that the move is a loss of potential.

The collection has proved especially valuable for law students interested in early American legal history or contemporary tribal claims, he told the News. To them, the documents are “a treasure,” and he expressed hope that the project would still be accessible.

“Otherwise, it feels like we’re throwing a hoard of Viking gold back into the bogs,” VanderHeijden explained.

Response on Campus

On Oct. 14, Grant-Costa and Glaza announced on the NNRC’s website that Yale’s Provost, with approval from the President, had denied the Collaborative’s request for funding because the NNRC did not meet Yale’s criteria for funding priorities.

In an email to the News, Polak said that Yale provided matching funds to the NNRC in 2017 after the project recieved a grant from the NEH. While Polak and Divinity School Dean Greg Sterling agreed to give those funds, Polak said that he and Sterling made it clear to NNRC directors and faculty advisors that neither the Divinity School nor the Provost would be able to continue supporting the project after the grant’s expiration in 2019.

Polak added that he and Sterling advised the Collaborative to seek outside support with the time provided by the 2017 bridge funding.

According to Polak, while he recognizes the NNRC’s benefits for both the Yale community and the University’s reputation among Native American groups, his position as Provost requires that he make “difficult choices” about funding requests for worthwhile projects. Polak added that in a meeting with the NNRC’s faculty advocates, Salovey explained that direct funding from the President or Provost — especially for a project that does not directly support faculty or students — is “rare.” Instead, the Provost generally provides funds to the leaders of units and Deans of schools within the University, who then decide how to distribute those resources.

Salovey’s chief of staff Joy McGrath referred requests for comment to Polak. When asked to comment, University spokesperson Karen Peart directed the News to Polak’s comments, stating that the University recognizes the benefits of the NNRC for the Yale community and that those benefits are “why a significant effort was made to give it additional time and resources to seek other funding sources.”

Polak wrote to the News that he hopes the NNRC can secure the funding necessary to continue its digitization of primary sources. He added that the University’s library system will retain the project’s online materials in its digital archives.

“We recognize the immense value of the collection and will ensure that it remains available for education and research,” Polak wrote. “Thus, although the university will not be funding the addition of new materials to the project, Yale will continue to make sure that scholars, students, and members of tribal communities can access and benefit from the documents and findings of the Native Northeast Research Collaborative.”

According to Meghanlata Gupta ’21, house staff member at the Native American Cultural Center and a member of the Sault Ste Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, Yale’s decision not to fund the NNRC is disheartening.

“I think any kind of involvement with Indigenous work is something that Yale should be making a priority right now,” Gupta told the News in an interview.

Gupta added that Yale’s relationship with Indigenous communities has been historically complicated. She acknowledged that positive programming involving Indigenous life is happening on campus right now, such a symposium for Indigenous People’s Month and an exhibit at the Yale University Art Gallery. Still, in Gupta’s view, events such as these happen largely as a result of student activism, not University efforts. She added that securing funding for events places a large “emotional and physical tax” on students — students who would prefer to focus on planning the events themselves rather than scrambling to track down grants and donors.

Madeleine Hutchins DIV ’21 and Anthony Trujillo DIV ’19 — members of the Mohegan tribe and Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo tribe, respectively — wrote in favor of the NNRC in an Oct. 27 op-ed for the News. Hutchins and Trujillo questioned the University’s commitment to dealing with its “fraught history” of excluding Indigenous scholars from its academic spaces and treating them “as objects of mission.”

“By discontinuing the NNRC, Yale has quietly severed the one program that grounds the university in its Indigenous history and maintains its ties to local Native communities,” they wrote. “In doing so, the university has disregarded and disrespected the many Native people who have contributed to and drawn upon the NNRC.”

Beyond New Haven

The University’s decision to stop funding the Collaborative has reverberated with Native American communities across the Northeast, beyond New Haven.

This past spring and summer, representatives from various universities and Indigenous communities also wrote to Salovey, urging the University to extend funding for the Collaborative. University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Professor Kathleen Brown-Pérez described in a June 27 letter to Salovey the role of the NNRC beyond academia, calling the project “global” with ramifications for Indigenous populations in the United States and beyond. Brown-Pérez is a member of the Brothertown Indian Nation.

“‘As a global research university, Yale nurtures ideas that change the world,’” Brown-Pérez wrote, quoting Salovey’s remarks last fall at a celebration honoring Pauli Murray LAW ’65. “I am certain these words ring familiar to you, as they are yours. I believe you meant them last November and you mean them now. It is clear that you understand that ‘global’ begins at home. ‘Global’ is nurtured at home. The pond into which the pebble is dropped is here. We cannot expect others to pick up the slack when we recognize a need for action.”

But academics were not the only people calling for action. Tribal Chief of the Nipmuc Nation Cheryll Toney Holley also wrote to Salovey, describing the NNRC as one of the only projects of its kind.

According to Holley, while the documents are written mainly from a colonial perspective, they still serve as a record of her and her people’s ancestors and represent a “largely forgotten period” in the history of the United States.

“It’s difficult to fully explain the joy (and sometimes anger and sadness) we experience while reading the documents and their transcriptions. (And when we see an actual signature!!),” Holly wrote.

Members of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gayhead (Aquinnah), the Mohegan Tribe and the Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe also sent letters to Salovey, asking him to renew funding for the NNRC.

What’s Next

For Grant-Costa, the past few weeks have been stressful. Two months ago, he waited eagerly for Yale’s decision and the fate of his brainchild, the NNRC. Now, he said, the project is on the lookout for new sources of funding — and the speed at which more materials, more fragments of a colonial past, can be uploaded is significantly stunted until that search is successful.

The documents he and his team have amassed over the years will still be available online, he said. But even though Grant-Costa said he has no hard feelings towards the project’s former home, the lost potential continues to sting. Faced with another move, he is left to wonder why Yale refused to support the NNRC for another year.

He listed the programs at the University where he believes the NNRC would have thrived: the Ethnicity, Race, and Migration Program. The Yale Center for the Study of Race, Indigeneity, and Transnational Migration. “We would’ve been a powerhouse.”

The NNRC document portal still bears the Yale Divinity School address. Its official email carries the Yale name. And its “About Page” says the project is based at the University. All of this will soon change.

Still, Grant-Costa said he is optimistic that the NNRC will survive — even without Yale’s support. The project has attracted attention from several universities in New England, he added, and he is toying with the idea of creating a consortium of schools that can split the Collaborative’s costs.

“It’s difficult, but I think with life there are these things that happen and then you have to adjust,” Grant-Costa said. “We’re trying to make that adjustment by looking for other universities that are interested.”

“I think other universities get it. I just think that Yale didn’t.”

Matt Kristoffersen | matthew.kristoffersen@yale.edu

Valerie Pavilonis | valerie.pavilonis@yale.edu