Jane, Africa, and the Sum Total of Sadness in the World: A Yale Medical student on his time in Uganda

Ashley Anthony

“What keeps bringing you back to Africa?” my wife asked the thin, shaggy-haired doctor. Having trained at Yale and worked in Rwanda for Partners in Health, he was in Uganda to teach a course on quality improvement.

“The same reason you guys are here,” he began as he sipped his Nile Special. “We don’t have to have a philosophical discussion, but I don’t think that pure altruism exists. I think we’re all here for similar things: a sense of adventure, a perspective on life when you are back in the States.”

We were having drinks at a hotel on Nakasero Hill, the fancy part of Kampala studded with embassies and private guards with assault rifles. As the black waiter brought out the bruschetta, I noticed that all the patrons except my wife and me were white. Beyond the walls of the hotel, I made out the buildings of Makerere University on the opposite hill. The slums, invisible from our seats, sprawled between the hills.

The past two weeks, I’d been working in the emergency room at Mulago National Referral Hospital, the largest public hospital in Uganda. Each morning, I walked into a room full of boda-boda (motorcycle cab) accidents, their victims sprawled on the concrete floor, flies buzzing around the drying puddles of blood. Many died before a doctor could see them. Patients who could not pay were left to die.

“This black stuff is air. There is air inside his skull.” I had held the CT scan against the sunlight for the benefit of the Ugandan medical students. “That’s bad.”

My wife was working in the infectious disease ward. There, fungi and tuberculosis multiplied in the brains of AIDS patients like mold on brie. When a patient died, the students packed the body’s orifices with cotton and moved the corpse to the hallway.

“What we do here is like a drop of water against a wildfire,” my wife said back at the guest house where we were staying for the six weeks of our global health elective.

On the other side of Earth, the Amazon was burning. The conflagration could be seen from space. If death emitted light, watching Earth from space would be like watching the cameras go off in a football stadium right at kickoff.

I grabbed a slice of bruschetta and downed my Tusker Lager. The doctor was right. I had come here not for altruism but for the adventure. I was a guy who, Ray-Bans over his eyes, AirPods in his ears, blurts out “sorry” before the homeless dude on the Green can squeeze in a word. Just like the hero of Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” who was tired of “the biggest, and the greatest, town on earth” (London in the late 1800s), I was tired of “one of the great cosmopolitan capitals of the Northeast” (according to infonewhaven.com). Residency applications were starting. Professional headshots, cover letters, resumes — the real world that I had postponed for so long was catching up to me like age on LeBron. I had longed for an escape, and my escape was Africa.

But even here, it was necessary to treat yourself once in a while. This hotel, its pool, the bruschetta — these were no different from the safety devices on a bungee jump. A rope made out of cash was always there to pull you back to safety. But I heard some people really get into Africa, the same way one gets hooked on bungee jumping. Some would find their bougie lives in the first world meaningless and disappear completely into the bush. The body wouldn’t come back up with the rope.

The night before our flight to Uganda, the party bikes packed with midlife crises going full swing on Crown Street, I stumbled upon a 1965 National Geographic documentary called “Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees.” In the documentary, the narration crackling like an LP, the 26-year-old Jane Goodall sits on a boat with a pair of binoculars, looking at the forest where she will make her groundbreaking discoveries on chimpanzee behavior. In the early days, before the chimps let her touch them, she would sleep alone in a hut built of palm leaves on top of a hill, where she watched the animals from afar. She would spend five years in Tanzania like this, a single blanket the only boundary between her and a world only her eyes could see. It is said that Jane Goodall suffers from prosopagnosia, the inability to recognize human faces.

One cannot imagine the loneliness that drove her there.

___

Uganda was a British colony when Jane first arrived in Africa. Driving through the country in 2019, you still feel a heightened sense of identity, a sense of power that comes from the unmistakable poverty of the place. Children in secondhand clothes from the first world wave at you from crumbling huts. Miles of forest spread beyond the unpaved road where goats, tethered dangerously close to the cars, graze on the seemingly unlimited grass. Battered 30-year-old Toyotas undergo roadside work until their revived engines spew black clouds among the boda-bodas that crowd the road like ants. All this is seen through a curtain of smoke from burning trash.

“Ni hao,” a man says, waving at me from a bus branded BLOOD OF JESUS as I calculate the best moment to cross a street. I am not sure if this is meant to be derogatory until the groom of a wedding we are invited to several days later greets us with “Ni hao.” I mean, you wouldn’t insult your wedding guests, right?

“You are from Korea? You people look the same,” the groom replies to me with a smile, offering me a plate of luwombo, chicken steamed inside banana leaves.

White supremacy, under attack in the states, remains orthodox in Uganda. Segregation here is maintained by simple math — a Ugandan can’t afford a $3 latte when the GDP per capita hovers over $600 dollars. Google is crowded with one-star reviews by African American travelers who were overlooked by the waiters as their own and thus ignored.

When they’re not saving lives or solving international conflicts, the expats in Kampala hang out in Prunes Café on Kololo Hill, where a farmers market is held every Saturday. Beyond the razor-wire fence, expats with colorful handwoven bags browse catered products like feta cheese and dark chocolate between pamphlets vouching sustainability. The inside of the cafe is decorated tastefully, with hemp bags of local coffee lining the walls.

“Better than Blue State,” I say after taking a bite of their almond croissant.

On the bookcase that also serves as a room divider, I find volumes of Monocle Magazine whose editor’s note talks about the process of selecting land for building a mansion in Thailand. The issue’s focus is South Korea, and inside, I find photos of chic places that I, a Seoul native, have never heard of. Korea’s beauty industry and K-pop, fueled by plastic surgery and slave contracts, are presented here as something exotic and sensual, while the gaudily optimistic foreign affairs section ends with a musing on the president’s cat, such that the magazine’s net effect comes to what bokeh achieves in photography.

On the wall behind me, I find a classified written by a maid’s previous employer who vouches that “she would often work overtime without being asked.” An unmistakably Scandinavian family, all four of them with sunburnt cheeks, walk into the cafe, with a black nanny trailing the kids.

A humanitarian is always a hypocrite, George Orwell wrote, and there is some truth to this. Most humanitarians — from your friend, who hosts a donation on Facebook for her birthday, to Bill Gates, who has donated over $30 billion to solve poverty — are simply incapable of sharing the life of the person they intend to help. It is hard to be true buddies with someone who has a seat on the first flight out of your country, Monocle Magazine in his seat pocket, while your family gets macheted into pieces, which, I hear, is what the UN did during the Rwandan genocide.

But what about those who stayed during the Ebola outbreak?

White saviorism aside, an extreme example of altruism is living nondirected organ donation, where a person voluntarily gives up a kidney for a complete stranger. These donors are scrutinized by psychiatrists for mental illness, and the surgeries are often delayed. Should we allow a living person to donate her heart? Altruism can seem inhuman beyond a certain line. Some may say to love everyone is equivalent to loving no one.

In fact, the best-maintained humanitarian efforts in Uganda are based not on altruistic feelings but on economic incentives. Look deeper, and every successful partnership is fueled by secondary gains. Don’t be shocked: The World Health Organization is funded and influenced by big pharma. The best funded department at Mulago Hospital is the Pediatric Oncology Department: All chemotherapy and diagnostic tests are paid for by Baylor University, with the understanding that the samples will be sent to Houston for medical research. It is ironic that the same child, cured of leukemia, will be left to die from a boda-boda accident a year later.

Hypocrite or not, it is hard watching people die. Back in the emergency room, I watch a man herniate his brain through his skull because his family could not pay for a head CT, which costs 200,000 Ugandan shillings, or 50 U.S. dollars. The same day, I watch another man bleed out to his death from his spleen while his wife breastfeeds their child by his bed. Another comes in with his mouth smashed in, his nose dangling by a thread of skin and his skull cut through the bone down the middle. “Gang violence,” the pink triage chart reads.

Sometimes all one could do was wipe the blood off a man’s face.

It is said that millions in foreign aid money to the Ministry of Health have been squandered in the resorts of Europe and the Middle East. The road laws cannot be changed because the politicians themselves own the hordes of motorcycles, leasing them out to the jobless youth for a daily cut of the profit. Yoweri Museveni, who has ruled the country for 33 years, will be elected again in 2021.

Each Monday, we have a debriefing session where we vent our frustrations to a Ugandan doctor. He, like many Ugandans, excels in the art of telling stories.

“At the time of the Rwandan genocide, there were so many corpses flowing into Lake Victoria that the government installed a sieve by the mouth of the river. What do you think happened? The sieve was overrun,” he tells us. “We are that sieve.”

____

I did what one normally does in such a situation: get used to it. I stopped counting the number of deaths. In the evenings, my wife and I passed the time without any idea of necessity, watching the monsoon pass or feeding the monkeys that lived by our guest house. At night, I read short stories by George Saunders, by candlelight when the power went out.

I had thought that going on a safari would be a great way to forget all the sadness in the world. After six hours of driving past smoldering brick kilns, skinned halves of goats hanging on hooks and girls in long skirts hoeing the red earth, we arrived at the national park to discover a fleet of trucks and Chinese headmen overseeing a bridge construction to an oil field. It is said that China will own half of Africa in 20 years.

Carsick and covered in dust, we crossed the Nile in a ferry to enter the northern area of the park. No number of National Geographic photos prepares you for the landscape of the African savannah. The majestic, green earth stretched in all directions without any human contraption to stop the eye. I stuck my head out the pop-up roof of our van and let the wind blow my overgrown hair wild.

“Giraffe!”

On the horizon, a tower of giraffes loomed like construction cranes. Soon, the brown specks among the grass enlarged into herds of antelope. The gray boulders in the distance, were those elephants?

A hundred iPhone photos later, we sped through the dusk to catch the ferry back to our lodge. As we crossed the silent Nile, the full moon simmering on its dark water, I found myself in that state of blissful emptiness that mindfulness gurus will teach you for $50 a session.

“I am scared to die,” my wife said, breaking the silence. “That baby antelope. It was so quick. I can’t imagine what dying, what not existing feels like. It’s scary.”

We’d been lucky enough to see a lion hunting. It had been a quick affair, the antelope instantly turning into a rag doll in the lion’s jaws.

“We’ll be there for each other when it happens,” I said.

“But you’re probably going to go first,” she correctly observed. “Can we maybe start going to church or get a religion when we grow old?”

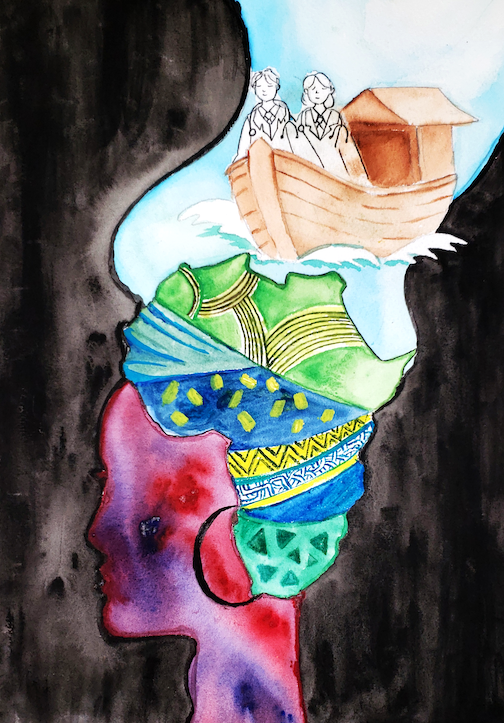

I had always been cynical of the church. To me, missionaries in Uganda seemed no more than paternalistic spectators of a doom from which they were spared. In this way, I was no different. I had watched the patients in the hospital like Noah watched his neighbors the day before the flood.

The hippos grunted under the water. I could have followed that river to Egypt where it drains into the Mediterranean, past Gibraltar to the Atlantic, and to the Pacific, to the small peninsula where I was born nearly 30 years ago. The sky was the lightest shade of black, the stars hidden behind the nearer light of the moon.

What do you tell your wife? That death will be painless and beautiful? That we will meet in the afterlife?

A quick calculation in my head showed that, with the cost of this safari for two, I could have saved a child born with cyanotic heart disease. I was already doomed to hell. But what can God expect from a frail creature that cannot outrun a hippo and dies from a single mosquito bite? What can such a creature do against an infinite amount of suffering?

The nerd in me remembered that subtracting a finite number from infinity does not change its value. The two sides of the equation are mathematically equivalent. But who cares about the mathematical properties of infinity? We all learn in kindergarten: You take a bite of something, no matter how big, and, as one of Saunders’ stories ends, “the sum total of sadness in the world is less than it would have been.”

All these questions were booted into a corner of my mind as I was walking past the golf course on Kololo Hill several days later.

“Sponges?” A kid, I would guess around seven, held up a set of bathing sponges.

“No thanks,” I said reflexively.

“Sir, kindly support me so I can get some drinking water.” The kid was a pro.

“Sorry,” I said and continued to walk up the hill.

“Please sir, I need some drinking water,” he pleaded as he followed me. “Madam,” he beseeched my wife.

“Should we have given him money?” I asked my wife once he had left us. “I kind of feel bad.”

“I don’t know, should we?” she replied, panting from the climb. “But I heard that giving out money discourages people from seeking employment.”

“But what if there are no jobs, period. What if this is his only chance? What if he really needs the water?”

When I turned around, he was already gone.

Wyatt Hong | wyatt.hong@yale.edu