Avery Mitchell

Earlier this week, I listened to one of the foremost political philosophers in the country speak about the distinction between convention and nature. This same professor also houses divisive beliefs on gender, sexuality and the way one ought to revere Western literature. I wonder, then, how Harvey Mansfield would feel watching a nearly all female cast pulsate to electronic dance music in Branden Jacob-Jenkins reimagining of Euripides’ Bacchae.

The morning after seeing Girls, I sat in my Directed Studies literature class discussing the air of homoeroticism, reinstruction and electricity in the dialogue between Dionysus and Pentheus. If only my class could be transported to the Yale Rep and watch as Dion, Jenkins’ Dionysus, squares off with his toxically masculine cousin, Theo. Dion, the god turned “curator” — someone who would have likely attended the Fyre festival unironically — strips to his underwear, with the neon band tight around his slim waist, inching his cousin off the precipice of convention and into the abyss of 21st-century discomfort. This confrontation feels familiar. It is the dinner table standoff between cousins of differing beliefs where one turns their nose at what is and is not natural.

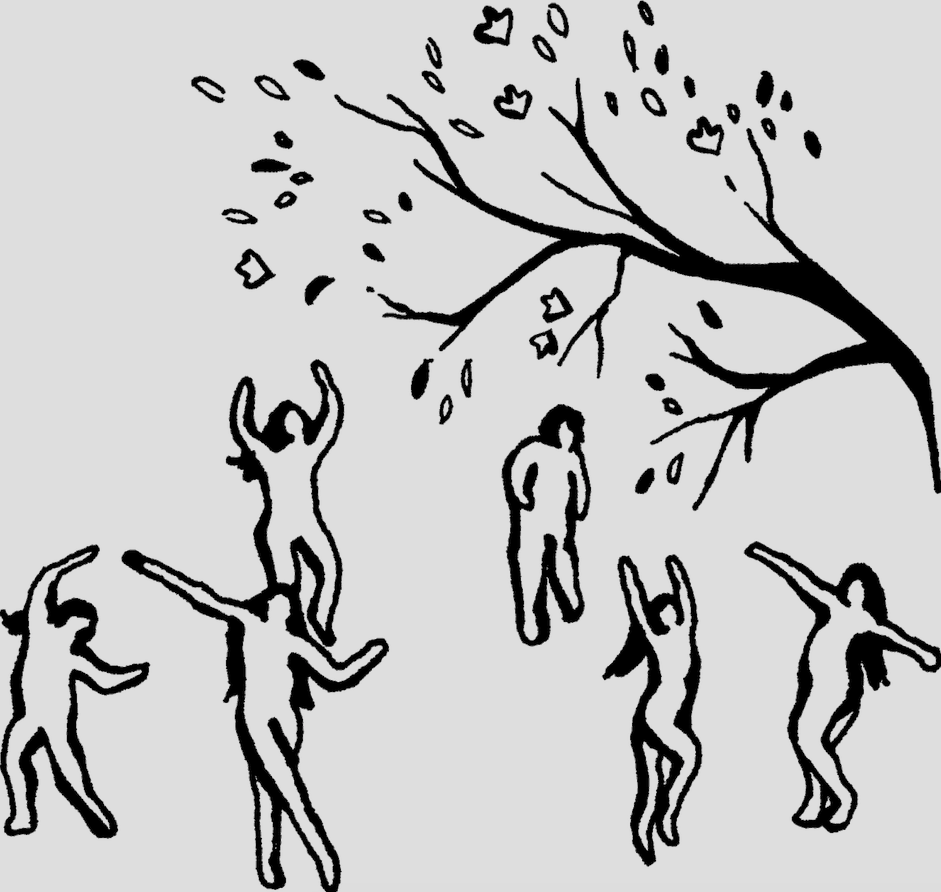

Nature is a seductive and funny mechanism in Jenkins’ world. The stage is a mountainside forest complete with rich vegetation that vacillates from green in daylight to nearly black under Dion’s ominous nightscape. Yet this forest could not be more unnatural, presented to us as more in the spirit of the “clurb” than the Cithaeron mountains. “Clurrrrrrbbbb” rattles from nearly every character’s lips at one point or another. The word choice seems appropriate since “clurb” implies the kind of night that begins at the club but ends on the curb, apt diction considering how the characters unravel by the end of the production. Possessed by the music, intoxicated, trapped in Dion’s spectacle, their hands and bodies are soiled with blood and sweat. And yet, when the attendees, or perhaps devotees, speak of the reason why they’ve decided to come to the party, the answers, playful parodies of the Euripides’ original Bacchae, are all one form of escapism or another. To what extent are the girls trapped? Is Dion pulling at the characters’ strings or is it the characters’ own desires to be both seen and invisible that compels them to dance like everyone is watching? The paradox of visibility one encounters at the club is not dissimilar to the most pervasive of our modern social experiences: for every declaration of our fabulous selves, there exists countless hours of forlorn lurking.

Despite the overwhelming modernity of the production, there is something primal, if not savage, about Girls. Perhaps it is the way both the wardrobe and choreography endow each character with either an animal print motif or direction to prowl the club like an animal stalking its prey. In this way, there is freedom in the space where women and men alike are simply the nameless “girls”, able to buck gender norms and shake their corporate, familial or romantic shackles in the face of the convention that imprisons them. At face value, Dion’s party is lawless and uninhibited, a refuge for the people who do not find power in convention but rather in nature as they degenerate into their primal form. However, this nature, like the set itself, is curated and false. The party must abide by Dion’s laws, conventions in and of themselves.

The Bacchae in Jenkins’ hands is witty and violent, a love song to both hedonism and masochism. His reimagination strikes a remarkable balance between the house of Cadmus and any suburban wasteland. The inclusion of live stream footage to depict the distance between Theo’s world of convention and Dion’s world of nature is, like all of Jenkins’ work, cunning. But perhaps the greatest strength of the play is that it is unconcerned with reinventing the story, reducing the Bacchae to some convenient parable. Rather, Jenkins masterfully collides two worlds, old and new, and allows the two iterations of the story to exist in the same breath. Girls is not a ghost story, a relic of Euripides. Rather it is a perfect echo, responding to Pentheus and Dionysus with words that are neither quite the same nor wholly different.

Ella Attell | ella.attell@yale.edu