Emily Tian

At an improbable hour in an improbable place, I find myself standing on a stairwell outside 220 York St., peering through a window into a darkened room. Inside, performers move their bodies fluidly and silently, while lush forest footage plays on the projector. For a few minutes, the dream hovers, broken only by the call “and, scene.”

Plays end. Actors bow, the curtains draw close with a velvet hush, and theatergoers stand up, stretch their legs and shake the numbness from their feet. Perhaps they pocket their playbills, present a bouquet to the lead and shuffle out of the balcony in line. Backstage, cast members might be rehearsing for another show the next day.

The Control Group, a student experimental theater ensemble, intends to disrupt traditional theater. Their name seems to be something of a farce; a control group is the meat-and-potatoes of any experiment, but it is also established and unaffected convention. This collective is anything but.

“Experimental theater means building some sort of performance that isn’t based on a script the way traditional plays are,” Jacqueline Blaska ’20, one of the Control Group’s three co-directors, said. What happens, Blaska wonders, if the regimented boundaries of theater are broken?

This year’s 15 active members spend their weekly rehearsals on Tuesdays and Sundays “devising” — a collaborative technique of theater-making. In a semesterly show, these devised pieces catch each other in the act of collision and transformation: two devised pieces may beget a third or respond to the questions raised by each other, or perhaps aspects of one may be transposed onto the performance of another. Last year, for instance, the Control Group recorded their dreams in a shared Google Docs journal, a collaborative project which inspired their spring show at St. Anthony’s Hall. This winter’s performance will be on Dec. 7, at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art.

Apart from shows, the group has also staged “happenings”: performance pieces across campus which fade away as quickly as they appear. After the first-year assembly in 2017, they greeted freshly minted first years outside of Woolsey Hall wrapped in silver emergency blanket costumes. Perhaps owing to these unpredictable happenings and its elusive online personality, the Control Group’s enigmatic reputation precedes it. They don’t seem to deny this kind of campus mythos. “Despite our love of mystery, being in the group is full of warmth and care,” Payson Whitwell ’20 said.

Students founded The Control Group in 2000; its 20-year history means that many of its alumni are working professionals, some of whom with established careers in the arts. Among its alumni include Jeremy Lloyd of the songwriting duo Marian Hill and Sara Holdren, a theater director and critic for New York Magazine.

The ensemble auditions new members in a two-round process every September. While Blaska is a theater studies major, many other members had no previous acting experience, instead entering the group from other interdisciplinary creative backgrounds — visual artists, musicians and dancers to name a few. Five new members joined the group this year, including Ethan Shim ’23, making this year’s ensemble one of the largest it has ever been. “I joined because they had a cool poster at the extracurricular bazaar, and I thought experimental theater sounded cool, especially because I had never done theater before,” said Shim.

This particular Tuesday, I’m supposed to be observing a rehearsal for The Control Group, so I rummage for a pen and notepad, ready to take notes while the 15 members practice and perform. Instead, as I pull a chair into their circle, they thrust me into the hot seat. Like friends egging each other on over an inside joke, they begin asking me questions, from the basic “Where are you from?” or to the glib “What’s your social security number?” I am worried that I’ll somehow give them a wrong answer, but they brush away my hesitation with more questions of the kind.

Apparently they’ve gathered what they needed from me, so they break off into three groups, racing up and down the stairs of the drama building. Blaska’s earlier note on how they “move around a lot” is hardly surprising; it seems like the very space they inhabit — the wooden benches of a court-like chamber, the upstairs bathroom, the stairwell outside — is a co-conspirator in their creative enterprise.

As one group writes word associations on the whiteboard, Lena Christakis ’20 is busy Googling lines from the children’s characters Frog and Toad, which I had described as an early childhood memory. There’s an urgency in the session that I didn’t expect, as if the single question “What if…?” were constituted as law. While they rely in small part on improvisation, their process seems to synergize the ordinary lifespan of a theatrical production at electric speed.

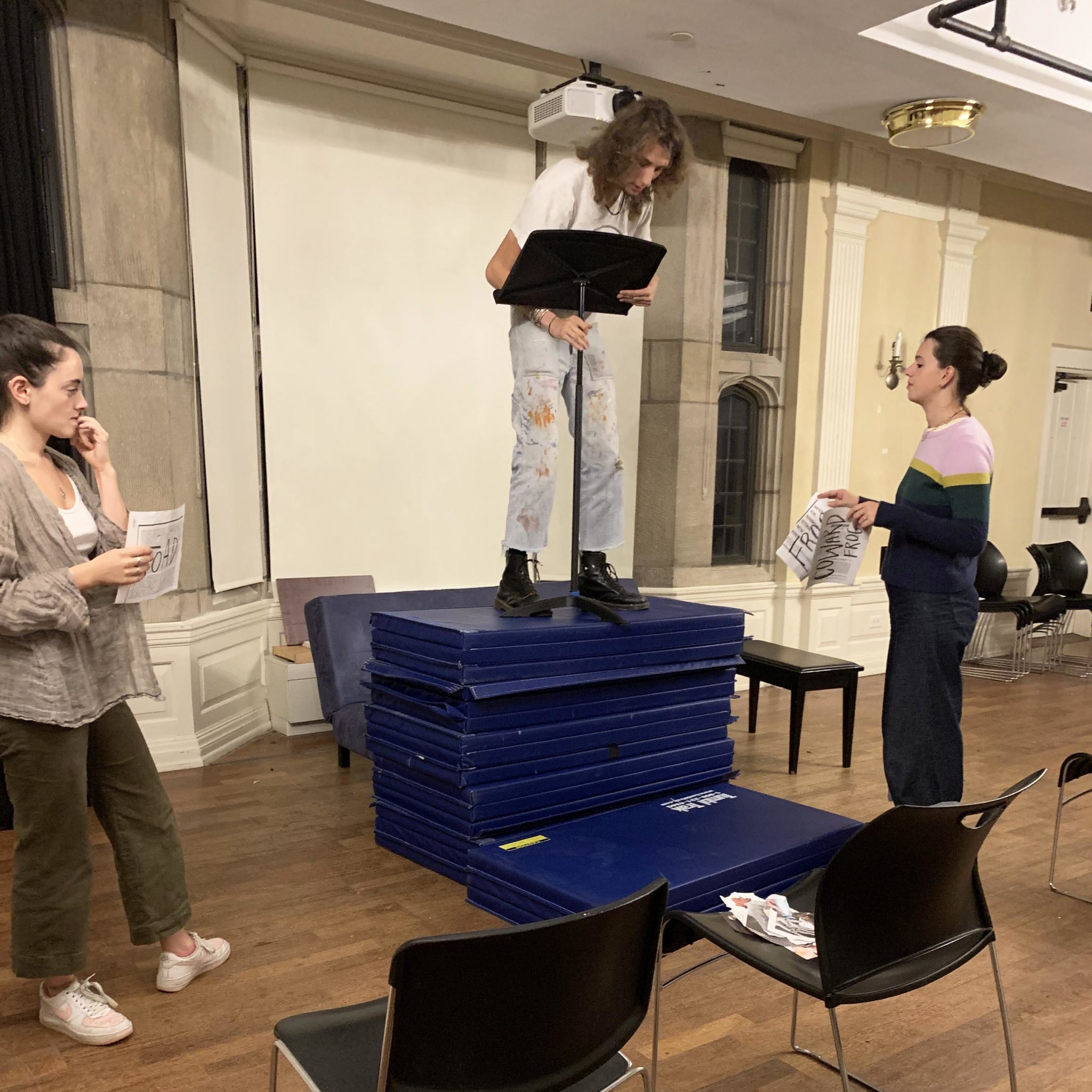

And what emerges from the spare half hour of devising doesn’t feel oversalted or avant-garde for its own sake. Each group, for a few minutes, takes turns performing their pieces. Blaska’s group becomes trees, riffing off my description of the color green; Ronan Day-Lewis ’20 stands atop a pile of blue gym mats and officiates a wedding between Frog and Toad. It is spectacle edging on the surreal. They deal with the liminal space between reality and imagination, horror and wonder. Some moments are so bizarre they become absurdly hilarious. While the third group acted out a diabolical confession, a laptop screen in the background plays a video of a crab-eating contest — presumably alluding to my home state of Maryland.

Experimental theater may as well be called experiential; the Control Group is sharp to acknowledge the audience’s engagement with their work. Blaska thinks hard about “how [they] curate an audience experience,” a serious assertion that seems to discredit a reading of their work as kitsch or gimmicky.

I become, in other words, something beyond a passive audience member, feet crossed and head swiveled in one direction. Why be deluded by distance? Grasping a Sharpie-on-newspaper invitation, I’m a guest sitting in the aisles of a strangely ritualistic marriage ceremony. Watching the silhouetted tree actors from the concrete stairs outside, I feel part transgressor, part discoverer.

“Sometimes it can be tempting for artists to think of themselves as outside of society as a commentator. I feel personally that performance is a really powerful and productive way of interacting with society, making connections and learning from other human beings, which is in itself a political project,” Blaska said. “I found that experimental theater has given me a synthesis of what I love creatively and artistically and what I care about as a human being in the world.”

Blaska’s conviction in the potential of experimental theater echoes the “About section” of their website, which declares, “we strive to create necessary theater.” This is a daring artistic manifesto, and I don’t quite know what necessity means.

Instead, as I watch their rehearsal, I am reminded most of childhood. Children have this way of making unlikely things matter, by asking questions you least expect or brandishing household objects in their games. The Control Group isn’t child’s play, but they seem to key into the authenticity of childhood wonder, repurposing that open imagination to drive their artistic process. There’s something to be said about the immediacy of their work, unsealed from the amber of a script performed hundreds of times prior. This kind of devised expression is simultaneously confessional and demanding. A crumpled bag of Tate’s cookies is transformed into meaning-making material. Same goes for an otherwise unremarkable stack of blue mats, elevated into a stage.

I, I, I. I catch myself returning, against most journalistic avowals of impartiality, to the personal voice. Because somehow it seems disingenuous to make The Control Group anything other than personal. “The trust that we have in each other is essential to the work that we do. It allows us to trust every creative impulse, no matter how strange, and push ourselves to make new, and even stranger, works,” Whitwell said.

Maybe this is necessary enough.

Emily Tian | emily.tian@yale.edu