Claire Mutchnik

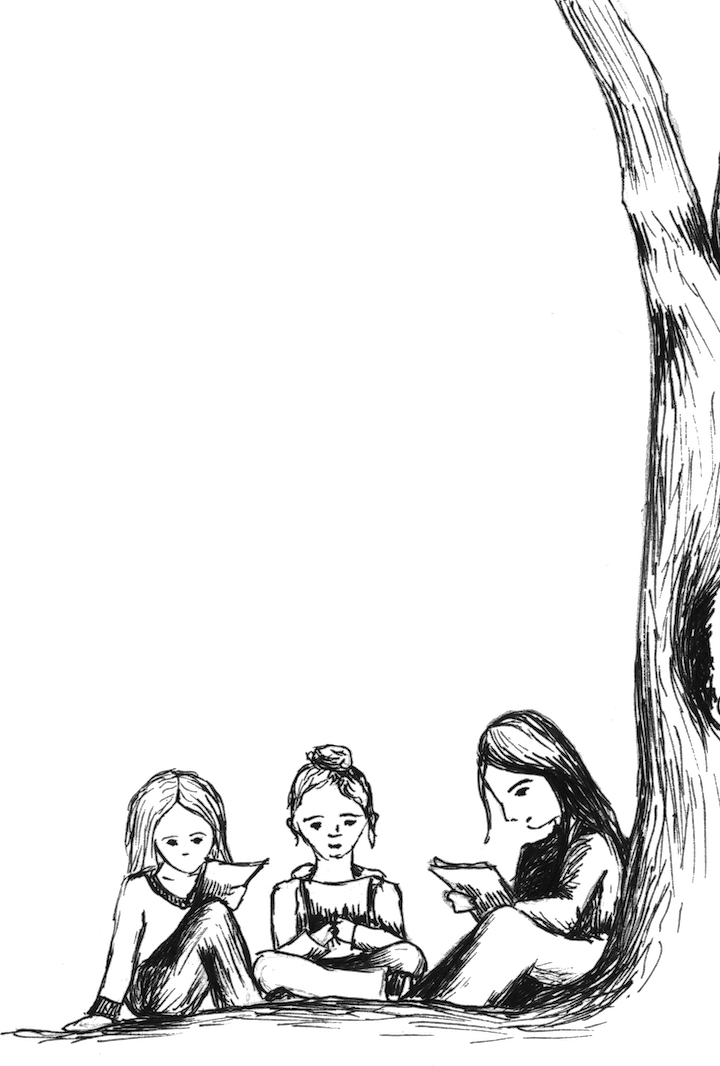

The July after my sophomore year of high school, I went to Kenyon College for two weeks to write in classrooms next to boys named Jared Gentile and Angus O’Connor and Calen Firedancing. They wore small gold earrings, read Ulysses and wrote poems about their pants dropping to the floor. I liked them. I made girlfriends named Juliette and Serena and Caroline, and we climbed trees in blue skirts and looked at each other’s lips as we read our own short stories aloud. I liked them, too.

In my fiction class last year, my professor told me that the best thing she did for her writing was fall in love with a writer. She married him, and now he is always the first one to edit her novels. Her husband knows which parts of her love plots are about him and which parts are not. He doesn’t get mad at her for conflating him and the person she used to love because he’s a writer, and he gets it. It was the best decision my professor ever made for her own writing career, when she married a writer.

This fall I am taking a class called “Love and Desire in the 19th Century.” We read Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning’s love letters, and I am surprised that they meet each other through fan mail. Robert has a crush on Elizabeth’s words. They write each other every day, and every day the letters become longer. Eventually, the two run off to Italy together to get married. Elizabeth writes her famous sonnet sequence and is cured, miraculously, from the staying scourge of feebleness she suffered her whole life.

I stop listening in class and begin writing down a list of all the famous literary couples I know:

Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning

and Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath and

Jack Dunphy and Truman Capote and

Zadie Smith and Nick Laird and

Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne

and Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West and

Emily Dickinson and Susan Gilbert Dickinson (maybe).

On the final day of writing camp at Kenyon, the teacher gave everyone in our class ten scraps of paper. We were supposed to scribble down nice things about each other and slip them in hands and back pockets before leaving to go home to our parents and backyards and the half-filled journals beneath our childhood beds. I left my phone number on the notes I wrote to Jared and Angus. Neither of them ever texted me, but I didn’t care. It felt bold and writerly. I kept their slips of paper in my desk drawer at my lake house, scrambled in with leaking bottles of blue nail polish, snapped hair ties and inkless pens. When my boyfriend, Ben, came to visit me at the lake last summer, he found them and read them and smiled.

“Who wrote these to you?” He asked me.

“My secret admirers,” I said.

Serena from writing camp visited me at school last May, four years after we first met. A group of her friends were coming to Yale for some society ball, and she needed a bed for the night. We had dinner, and she touched my hand as she told me about the three different men she had fallen in love with in her past three years at college. One was an activist, one was an actor and the last was an asshole. Everything she said was overly romanticized in the way that I had found mystifying when I first met her as a sophomore in high school. Four years later, she still delighted me, but in a way that sometimes made my eyes roll. It was good to see her.

After dinner, Serena came back to my room and undressed and then dressed again for the party. As I watched her undress, I remembered how beautiful she was andz the time we undressed together. We went streaking around a church at Kenyon with Caroline. It was so silly and stupid and obnoxious and then Serena started crying because she felt it was sacrilegious. I thought that was silly too, but I still wanted to hold her. The dress she wore to the party was a deep pink.

When Serena came back from the ball she was drunk and I was sitting in my living room with my boyfriend, Ben. She told him the story about how we sang together at the talent show over and over until he told her he was tired and needed to go to bed. He left and she moved closer to me. She started whispering into my neck about the party and the dancing and the boys she had already told me about over dinner. She began to cry and laid her head down on my lap. I held her and I wondered if she noticed how close we were, and then I went to get a blanket from my room. She slept on the couch and I slept in my bed. The next morning, we ate breakfast together. She left.

Last week I texted Ben that we had finally finished Moby-Dick in my American Lit class and he texted back, “Thank fuck. You can burn it now.” Next is Emily Dickinson, I told him. He texted back, “Is that the name of the book or the author?”

I added to my list:

and

Emily Dickinson and Susan Gilbert and

George Saunders and Paula Redick and

Constance Lloyd and Oscar Wilde and

Junot Diaz and Marjorie Liu and

Sartre and de Beauvoir

I love Ben for many reasons, and one of them has been that he does things like ask me who Emily Dickinson is. He doesn’t read a lot of American literature. He is from Johannesburg and is very good at baking and knows a lot about the Liverpool soccer team and the rhythms of music and math and rare species of birds. When I read my stories aloud to him, he kisses me on the shoulder and tells me that I really painted a picture with my words. Usually, I pretend not to hear him when he says this. I pretend to myself he said nothing at all.

I wonder what it means to be serious about writing and what it means to be serious about love and what it means to be serious about these two things together. Sometimes my list of lovers feels long and sometimes it feels very short. Mostly, I am not adding to it and I am not reading it and I am not even looking at it. Always I am carrying it.

I just remembered this: When Ben and I first fell in love, he wrote long poems to me whenever he was on an airplane. I had forgotten about these poems that he wrote to me until now, and I now am remembering how good they are. I am remembering writing back to him and how good it was. I am remembering how our poems to each other were like lists, and I am wondering if everyone in love is a writer.

Ryan Benson | ryan.benson@yale.edu