Logan Howard

At the beginning of this semester, over 40 students from across campus flocked to 35 Broadway to eat cookies and speak with professors about classes and research opportunities. They came to this open house excited to learn about a program whose entire existence was threatened just months ago. Ethnicity, Race and Migration has now claimed its place in the University.

In March of 2019, the 13 tenured professors in Ethnicity, Race and Migration made the decision to withdraw their labor from the program after years of negotiations over the program’s status with the University. In a letter to Tamar Gendler, the dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, they cited the administration’s failure to give ER&M the power to hire faculty on their own and their refusal to fully recognize the program’s academic value as their reasons for leaving.

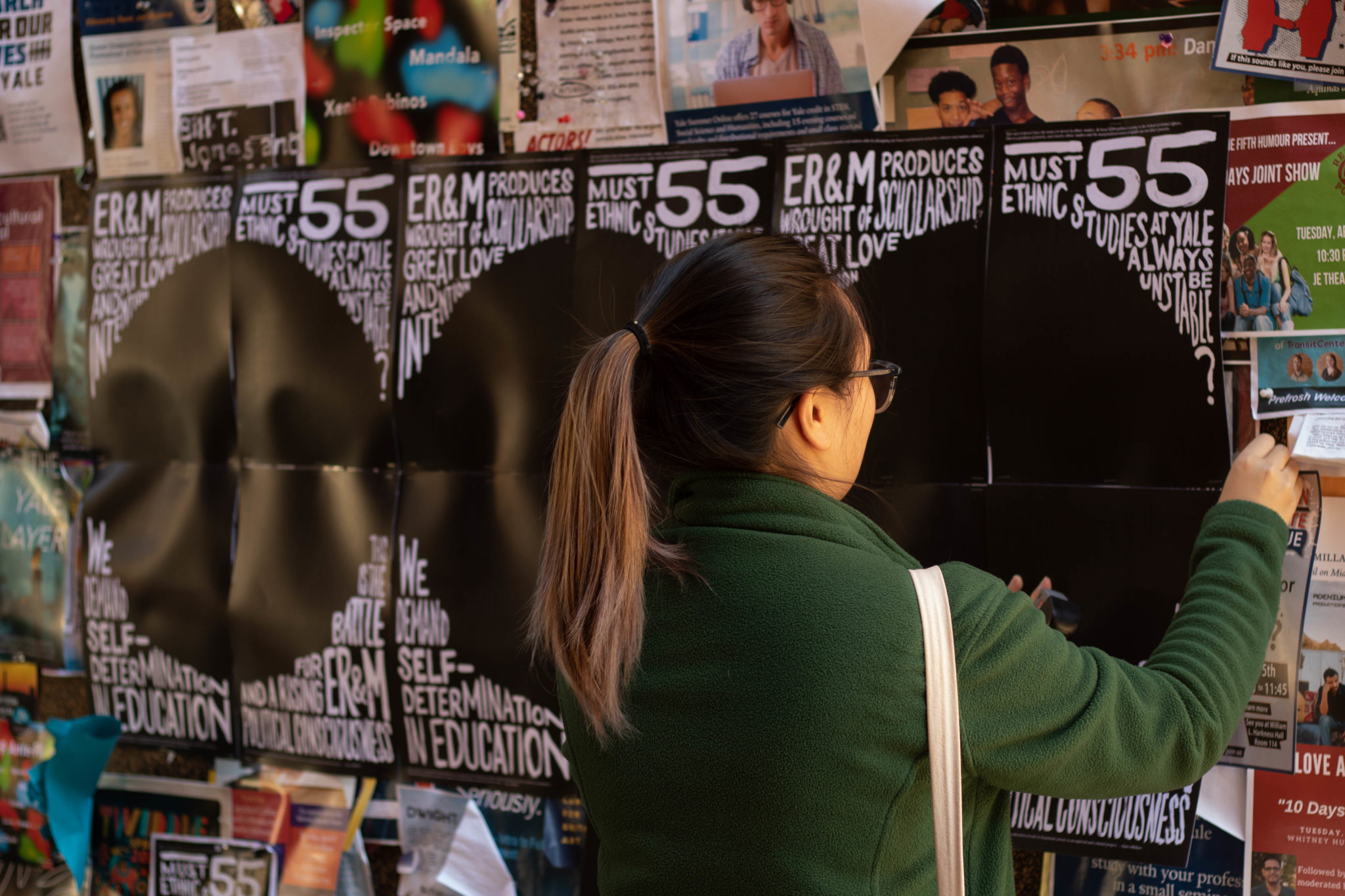

In the months following, students in the major mobilized in support of the professors, holding protests around campus and demanding that the University provide more resources to the major. On May 2, ER&M Chair Alicia Schmidt Camacho announced that the 13 faculty would return after the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Faculty Resource Committee voted to allocate five permanent faculty slots to the program.

But by the time residential colleges emptied for the summer, many students were still left with the question: What do these changes mean?

“To get to this place is an amazing triumph,” Camacho told the News. “We now have the structural capacity to build and have control over our own mission. Where we go from here is the same as any other academic unit on campus. We didn’t want to be exceptional, we wanted to be in the existing structures that organize academic departments and programs at Yale.”

According to Camacho, these five hiring slots given to ER&M will ensure the permanence of the program, which the professors believed was “unsustainable” without this control over their future. Many professors were frustrated with what Camacho termed the “revolving door” of faculty who left the department for various reasons and could not be replaced because the program was only offered slots on an “ad hoc” basis.

Confusion about the program’s status and hiring power have plagued its efforts to grow in the past several years. When professor Daniel HoSang and current Director of Undergraduate Studies Ana Ramos-Zayas were brought on in 2017, they believed their primary appointment would be in the ER&M program. Instead, they discovered that their formal appointments would be listed in other departments, as there was no formal structure to do so through ER&M.

Camacho said that the program slots will ensure that they can hire a professor specifically for the program without the need for a joint search process with other departments. The program is currently working to fill these new positions, potentially through a “cluster hire” where they will bring in several scholars who specialize in the same area, according to Ramos-Zayas. They are also currently in the process of hiring a new professor through a joint search with the Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies program.

HoSang added that it was previously difficult to recruit new faculty amid an unsupportive environment where people’s positions were not clear, and the administration’s new commitment will allow them to bring this new structure to potential hires.

Gendler told the News that reallocating the “pool” slots to “program” slots on a longer-term basis would not change the original size of the program, but it would allow the ER&M faculty to “engage in longer-term planning” in a way which was not previously available to them. She emphasized that these slots were already set aside for ER&M, although they were sharing hiring power with other programs.

“We are cautiously optimistic,” Ramos-Zayas told the News. “We like the fact that at least now, the University takes us seriously and that students see this as very relevant to their life. I think we were very marginal before.”

These material changes in the department also appear to signal a shift in the way that the university views the legitimacy of ethnic studies scholarship. Camacho said that these new faculty slots are a commitment to the legitimacy of the “intellectual project” of the program, as opposed to the administration simply seeing the ER&M professors’ work as “student services” or a “political project.”

She believes that having the stronger foundation of these positions will enable the program to gain more legitimacy in the eyes of other departments and contribute to larger conversations about the direction of the University.

Despite this progress, many of the professors did affirm that this is just the beginning of changes to restructure the program’s position in the University.

“Some of the concrete has been poured, but there is still a lot more that remains,” HoSang told the News. A larger physical space for offices, more administrative staff and resources to bring in more teaching fellows are just a few of the tangible changes that the program would like to add. Camacho emphasized that not everything has been resolved, but they now have the structural capacity to build ER&M.

Students in the program, however, are also skeptical about what these changes will mean for their own academic futures.

According to the most recent statistics from the Registrar’s office, there are currently 78 students listed as Ethnicity, Race and Migration majors. Ramos-Zayas also said that several more students have spoken to her this month about adding ER&M as their second major.

“We have more faculty, more possibilities for classes, more students, but that doesn’t change the way that Yale as an institution looks for us and provides for us the way an institution should,” Grace Ambrossi ’20, an ER&M major and a leader in the Coalition for Ethnic Studies, said.

Just this month, complications with the increased demand for ER&M classes became clear when over 300 students shopped HoSang’s lecture course “Race, Politics and the Law.” Many students were left struggling to find a section, and the class eventually increased the number of teaching fellows from five to 11. Ambrossi pointed out that there is still a need for more ethnic studies classes to fill a gap in this moment.

EC Mingo ’22, who declared as an ER&M major the day before the professors withdrew last year, told the News that despite the commitment to make more hires, there are still not enough resources to accommodate the growing number of students in the major. Mingo emphasized the importance of the accessibility of ER&M faculty and feared that there are not enough professors to meet students’ needs.

Some are attributing this demand to the increased visibility that the department has after the events of last spring. Irene Vazquez ’21, also an ER&M major, said that several people not in the major have asked her about what classes to take, which she believes is correlated to the efforts of students and faculty to emphasize ER&M’s importance within Yale.

Bella Bolayon ’23 first saw ER&M as a possible major during Bulldog Days where she witnessed the teach-ins and advocacy which tried to inform accepted students about the program’s crisis. She was enthusiastic about the critical lens that ER&M provides into other areas of study and the unique community that exists within the program. Now a first year, she is planning on declaring ER&M as one of her majors.

Janis Jin ’20, who was also a part of the Coalition for Ethnic Studies, pointed out that there is still a need for ER&M students to advocate for their place at this University, even if they won’t be around to see the fruits of their activism. She said that younger students are going to be the “energy” of the university and will play an important role in the future of ER&M as they try to build a stronger foundation.

While history professor Mary Lui does believe that the visibility of ER&M has increased since the spring, she also added that students are coming to ER&M to find an education that is relevant to the most pressing issues today. In a time of national conversations about race and immigration, she believes that programs like ER&M help students to process events that are affecting their own lives and find the language and historical context to discuss these issues.

In this time of rapid change in the program, those involved with Ethnicity, Race and Migration are still hopeful for the future. Ramos-Zayas said that faculty are committed to maintaining the same level of community that the major is known for, and they are trying to bring in scholars who will continue to demonstrate how ethnic studies scholarship can be applied to students’ futures.

“When you have ER&M students in the classroom, you can tell,” Ramos-Zayas said. “There is something very unique about the critical thinking and engagement they bring in. At the end of the day, it isn’t just about the faculty; it’s about the students. And the kinds of students that we have are just unbelievable.”

Carolyn Sacco | carolyn.sacco@yale.edu