A familiar face enters the black box theater in a new light. The iconic mop of playful curls is now clean-shaven. Tarek Ziad, DC ’20, is no stranger to the Yale performance community or the Yale community at large. He performs his senior project with new gravitas. This Tarek is not quite the one who taught us just how much there is to love about New Haven! No, this Tarek is here to tell us what he does and does not know about color, comedy, family, religion and, perhaps, himself.

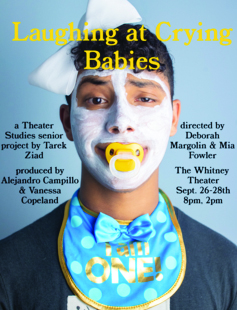

“Laughing at Crying Babies,” Ziad’s senior thesis project, begins with him in whiteface, a bold beginning to a bold set up. He moves from soliloquy to stand-up, traversing racial tropes, childhood memory and meditation. Ziad only briefly wears whiteface, something he applies and removes himself as the audience watches him peer into the mirror of his white dressing table, a prop that feels both feminine and old-fashioned. The whiteface seems to serve two purposes. The makeup gives the audience their first foray into the way Ziad plays with literal and figurative color; everything in the set, except the main actor himself, is ostensibly white, existing in stark opposition with the black box theater.

Moreover, the costume allows Ziad to consider privilege and introduce the audience to his own lack thereof. The whiteface character, Chris, with his inherited Midtown apartment, ease and entitlement, prefaces the childhood obsession with the Chris “type” that Ziad later reveals.

When the makeup comes off, Ziad engages in a more explicit conversation on race. The script here is rich. He savors words like “discourse” to make political rhetoric sound like a dish best served hot. Ziad is clearly cognizant of the way conversations on race and identity have become cheap soundbites meant to satiate the masses who either a) condemn the soundbites or b) participate in hashtag activism. Ziad is mostly successful in avoiding the pitfalls he critiques. He couples hot-button topics with reflection on his personal experience.

In these moments of reflection, Ziad shines. The single microphone onstage is a weapon for much of the performance. Sometimes the microphone exists for Ziad to use for his stand-up, the kind of humor he employs to eviscerate the audience. Other times the microphone is Ziad’s way of speaking directly to the audience to show his own fragility. In one of the most affecting moments of the show, Ziad stands at the microphone and bellows at the audience in a voice one presumes to be his father’s expressing disgust at his son’s sexual orientation. His eyes lock with the audience, his body possessed by the words he knows by heart, immortally internalized.

Perhaps the introduction of internal thought to the outside world is another strength of the show. Ziad welcomes the audience into his mind and, quite literally, his therapy session. Lying flat on the kind of chaise lounge that has become synonymous with the kind of MDs not everyone’s mother believes in, Ziad confronts his experiences as a first-gen child of slim means. At first, the therapy feels fresh; it’s interesting to see our leading — and only — man share long-harbored thoughts for what seems like the first time. When Ziad speaks plainly about his complicated envy and hatred of white families, the internal-external tête-à-tête works well. The audience can feel Ziad reckon with feelings he himself is still exploring.

However, aspects of the therapy setup feel too contrived at times. Take the Fisher Price Farmer Says See ‘n Say, a plastic toy intended to teach children animal sounds, that sits enigmatically in the therapist’s office. At first, the prop is a smart take on life’s wheel of fortune and works well with Ziad’s commentary on luck and privilege. But when Ziad slips into the therapy frame, his eyeline is inconsistent and slightly jarring; it’s hard to tell who Ziad is speaking to. As the show escalates, he takes to shouting directly at the toy wheel as if to both lament and look for answers in the fickle fortune that gave him the upbringing he treats with minimal affection. The abrupt reveal of the therapist’s identity feels intended to shock, a thematic cherry on top. Perhaps the toy would function better if the audience is left to draw its own conclusions on where Ziad looks for answers.

After Chris’s monologue, Ziad never returns to whiteface. The lack of follow-up makes the performance feel more like a collection of vignettes than a cohesive arc, perhaps appropriate given the diverse talents of its leading performer.

And maybe the lead himself is the show’s greatest asset. The audience enters knowing Tarek as campus’s talented funnyman but leaves with a haunting realization: how frequently we laugh to keep from crying.

Ella Attell | ella.attell@yale.edu .