Avery Mitchell

Fuck Indiana. The endless miles of nothingness — so uniquely Indiana — only compounded my sadness as I began my 10-hour drive to Charlevoix, Michigan. A state which forces people to drive five hours to reach somewhere remotely interesting — Chicago to the north, Columbus to the east, Saint Louis to the west or Louisville to the south — infuriates me. But I had no choice, since it all started in Louisville’s east end.

The east end lies on the border of Jefferson and Oldham counties in Kentucky, a quaint area of town full of quaint churches, sober people, and even more sober lifestyles. On Oldham’s side was Beau, a straight-A student, champion swimmer, governor’s scholar and the son of a wealthy and prominent conservative family. Not to mention tall, blonde and handsome. On Jefferson’s side was me. I couldn’t have come from a more different background. My family came to America with 100 dollars and two suitcases among the four of us. I lived in a single parent household with my grandparents. The only thing we had in common was that our straight-A’s were the only straight thing about us.

I came out at the beginning of my senior year, but Beau had yet to come out to more than a handful of close friends. As the years dragged on, it took a toll on me to monitor every little thing I said and did in order to sustain my straight image. I started coming out to a few friends my sophomore year. With their support, I built the courage to come out to my mom in the summer of my junior year. I had arranged to stay with my best friend Henry if things didn’t go well. I sat my mom down at the Comfy Cow ice cream shop positioned right before the TSA checkpoint in the Louisville airport. I was leaving for a three-week summer program in Berlin and I thought if it went poorly I would have three weeks away from home to sort my life out. My heart beat uncontrollably as I tried to make small talk, trying to muster up the courage to say, “Amma, I’m gay.” I did it. Her face was struck with shock and confusion. After a few questions and answers, she excused herself to the restroom. After what seemed like an eternity, she returned, eyes swollen, and her cheeks tear-stained. I asked her if I can still live at home, and she responded, “Monae, don’t ask questions like that. You’re my only son. How could I ever kick you out?” As my departure time approached, she hugged me goodbye, reminds me that she would always love me and tells me not to worry. With the encouragement of my friends and family, I came out to everyone else in September of my senior year through a post on Instagram.

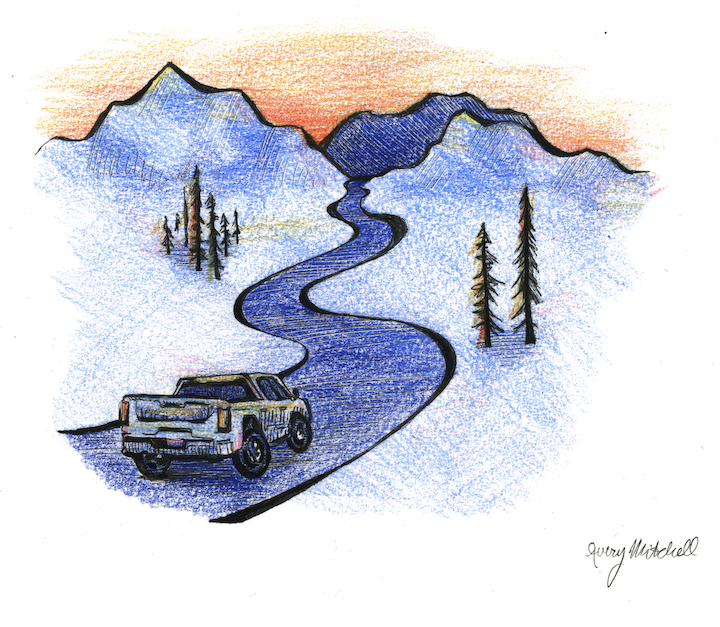

Beau and I met as anyone else meets in our generation: sliding into each other’s Instagram DM’s. We had mutual friends and I wanted a high school love story to tell my grandchildren, so with some convincing, I shot my shot. We were each other’s first boyfriends and we spent almost every day together. Our favorite date night activity was driving in his brand new Lexus — he rightly believed I was a bad driver — through all the back roads, getting lost and finding out where we were 30 minutes later. As I drove toward Charlevoix, I realized it made perfect sense to find myself in my own car, driving halfway across the country to, in a way, feel closer to the person I’d lost.

We were both at a special time of our lives when we met and dated: second semester of senior year. We both had committed to colleges and the only thing we had on our minds were our friends, our family and each other. We were happy together even though Beau wasn’t out. He said he’d be out and proud at the University of Alabama, since he wouldn’t have to worry about his parents or his other friends finding out. I didn’t pressure him. There was nothing more freeing, rebellious and awe-inspiring in my mind than an interracial gay couple falling in love under the Kentucky sun. Gay marriage had been legalized barely three years prior, and both of us could have been fired from our jobs if our bosses found out we were gay–Beau was a lifeguard and I was a manny.

En route to Michigan through Indiana, five hours of driving never seemed so eternal. More corn? What a surprise. With nothing but Indiana to soothe my heartbreak, my thoughts turned to prom night. Cliché as it is, I keep replaying it as one of the best nights of my life. My best friend and I won prom king and queen. The cheers, the smiles, the happiness was just overwhelming. I didn’t even mind that the crown was made of cheap plastic and bought in bulk from Dollar General by the school ten years ago. All that mattered was that I was in the moment with my best friends and my boyfriend. I never would have believed that the same chubby Indian kid with an accent — who came home from school crying every day because he got bullied so relentlessly — could finally be himself. Out, proud and, most importantly, happy.

I thought everything was going great until I got Beau’s “We need to talk” text, just a few days after prom. We decided to go for one of our hallmark rides. He said that he felt as though I showed him off too much. He was worried that word would get back to his family and school that he was at prom with a guy. I explained that it would have been rude not to introduce him when people asked me whom I brought. We could not have seen the situation from more starkly-opposed angles. He finally said, “Abey, I have never opened up to anyone as much as I have with you. But honestly, I still see myself with a wife and kids in the future even though I know I’m gay.”

Remembering that day, I felt myself clenching the steering wheel. I remembered clenching the leather armrest of his car just as hopelessly as I tried to understand how the man I loved could justify his cognitive dissonance. On that day, little did I know this would be our last ride together. In the week that followed, we barely talked. Beau sent me a text during the school day, during finals week, saying, “I don’t see a future here.” A future of me being gay. A future of him being gay. A future of us being gay together.

With miles of Indiana still ahead, I adjusted my rear view mirror. Though I had shown Beau that my family had accepted me, that my friends had accepted me and even that my school had accepted me, he wasn’t able to accept me because he couldn’t accept himself. He had been pushed, shoved and jostled so far into the closet that it was unthinkable for him to be with another man. A sin above all sins. An eternity in hellfire. The works.

And to be honest, I still don’t blame him. Who really could? What else could someone possibly think when his father gay-bashes at home, his “bros” gay-bash at school and his priest gay-bashes at church. The triumvirate of forces in his life — his family, his friends and his God — abandoned him when he needed them most by his side.

When Beau broke up with me, I reflexively took a screenshot of his text and sent it to my three best friends. Henry called me immediately. He was in the car with his family, on their way to Charlevoix, Michigan for Memorial Day weekend at his grandfather’s lake house. He put me on speaker and demanded that I come up to Michigan to take my mind off things. I had demanded the same of him the previous fall, to come to the park with me to take his mind off things when he called to say that his girlfriend had committed suicide. As childhood friends, we could always rely on each other when it came to anything, from goofing off in Econ together, to crafting the perfect DM, to family drama and everything in between. As seniors, we learned how to support each other in problems that were beyond our years.

I had to get out. So I did. At around 11 a.m., Beau broke up with me; by 12 p.m., I checked myself out of school, and by 1 p.m., I had my bags packed, gas filled and was on US-31 North to Charlevoix, Michigan, prepared for my 10-hour drive. Writing this now, two years later, that’s where I am: a Charlevoix state of mind. That day, I found myself consumed not by hate or sadness, but by love from Henry and my other friends and family.

In a way, we all have our Indianas. A necessary transitory state that makes no sense in the moment, a journey that might hurt you in ways you didn’t know you could be hurt. But Indiana, like pain, is never forever. There’s always a destination above, or rather beyond, Indiana that makes it possible to keep driving. And it does get better.

Since starting college at Yale last fall, I’ve often been asked what was it like to grow up gay and brown in Kentucky. I spent my adolescence shaping myself into who I thought people wanted me to be. I meticulously transformed myself from the sad, chubby Indian immigrant kid to a tall, more fit, Yale-bound valedictorian and prom king, who just so happens to have a slight country accent. But ultimately that led to the undoing of me — and of us, more specifically. Beau wanted to fit in so badly. He just wanted to be “normal,” but I only wanted to be with him.

Perfect grades, perfect family, perfect car, and it still couldn’t get him through Indiana.

Abey Philip | abey.philip@yale.edu