Marisa Peryer

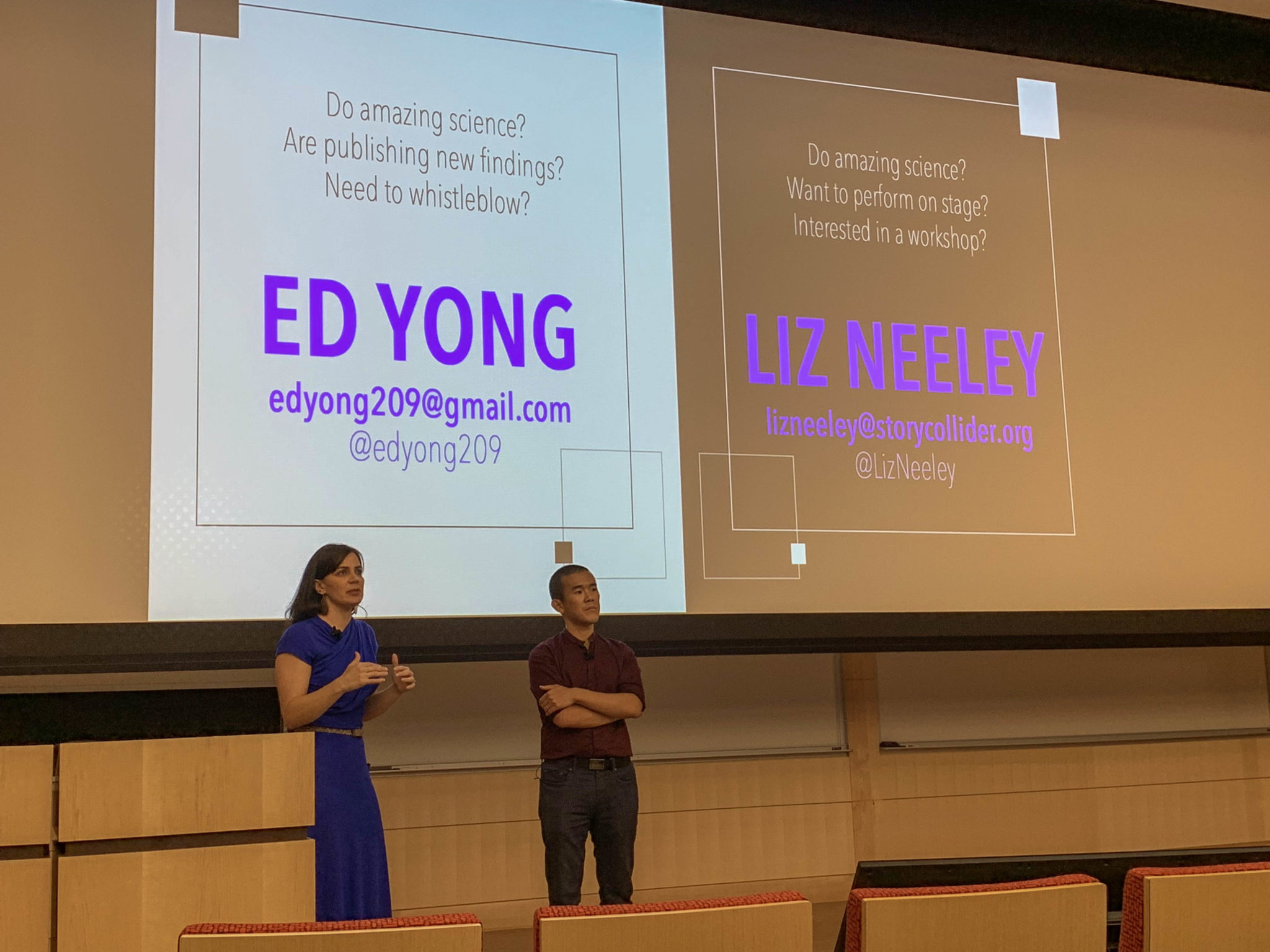

Ed Yong — a staff writer for The Atlantic — and Liz Neeley — director of the science storytelling nonprofit The Story Collider — made a case for the narrative potential of science to a nearly-packed auditorium in the newly-constructed Yale Science Building on Monday.

Throughout the talk, Yong and Neeley took turns sharing insights and anecdotes from their personal work. Their natural banter drew laughs from the audience as they displayed some of Yong’s lighthearted headlines, played video clips and drew analogies to memes.

“Narratives tend to be more interesting, more comprehensible, more believable and more persuasive than even more rigorous, well-marshaled arguments about the facts in the world,” Neeley said.

Yong illustrated this point during the talk, referencing a one-star review of his book that criticized its lack of footnotes, lists and diagrams. He argued that writers can tell accurate and moving stories about science in ways that are not information-dense or data-heavy.

“Elements of failure and success, joy and frustration, quests and mysteries, are part of the scientific life,” Yong said.

But effective storytelling is not easy. Yong said that he assumes his audience is bored, distractible and can stop engaging at any time. Thus, he is “constantly battling for people’s attention,” he said. Neeley acknowledged that for members of the STEM community, crafting a compelling narrative for their work may seem like an added responsibility. She suggested, however, that storytelling allows scientists to better understand themselves, and ought to be seen less as a product but a process built into scientific research.

Much of Yong’s work takes obvious delight in the curiosities of the natural world. Some of his most widely read pieces have focused on hippo defecation and slime-producing hagfish.

But journalism, he said, is as much about “acting as a watchdog to science as it is about celebrating its positive aspects.” His obligation as a journalist, Yong remarked, is “not only to tell good stories but also to unravel bad ones.” For him, this has meant writing articles about moral and ethical questions, such as using gene-editing technology on babies.

Stories are not just tools for understanding the world, Yong and Neeley said. They also shape science and our conception of scientists. Yong shared that he caught himself quoting far more male scientists than females in his articles and resolved to correct the imbalance by finding more diverse sources. And Neeley pointed out that viewing the stereotypical scientist as a “white man with crazy hair doing dangerous things” has excluded women and marginalized groups.

In an interview with the News, Yale molecular biophysics and biochemistry professor Carl Zimmer — himself a prolific science columnist and bestselling author — said that part of Yale’s investment into the sciences involves bringing speakers such as Yong and Neeley to campus.

“If people are doing great science and no one understands what they’re doing, it’s like a tree that falls in a forest and doesn’t make a sound,” he said.

For students in attendance, it was an opportunity to learn from renowned figures in science journalism. Sarah Mohr GRD ’23, a graduate student in Yale’s interdepartmental neuroscience program, said the talk gave her insight into communicating scientific findings outside of grant writing.

“Being able to reach a broader audience in a beneficial way is not a betrayal to yourself as a data-driven scientist,” Mohr said.

The event on Monday was free and open to the public.

Emily Tian | emily.tian@yale.edu