Katherine Yao

I wake up earlier than usual for a Sunday morning, cut up an apple to eat and get myself a coffee to drink along the way. Back at school, I love early weekend mornings — looking out the window and watching the trails of people walking around the courtyards grow, when the sun comes up and the day begins. This morning, though, I make my way from Russell Square down to St. Paul’s Cathedral. My hair is still drying in the not-too-chilly air, and I put in my headphones to listen to the news.

Getting closer to the cathedral, I hear the church bells playing. Their sound floats through the air and I imagine the bells creating little ripples, rattling the quiet storefronts, waking and welcoming people across London. I walk through Paternoster Square and look around at people drinking coffee at small tables, their faces lit up by the warm sun and the clear sky. I love the celebration of the morning — each person has their own ritual.

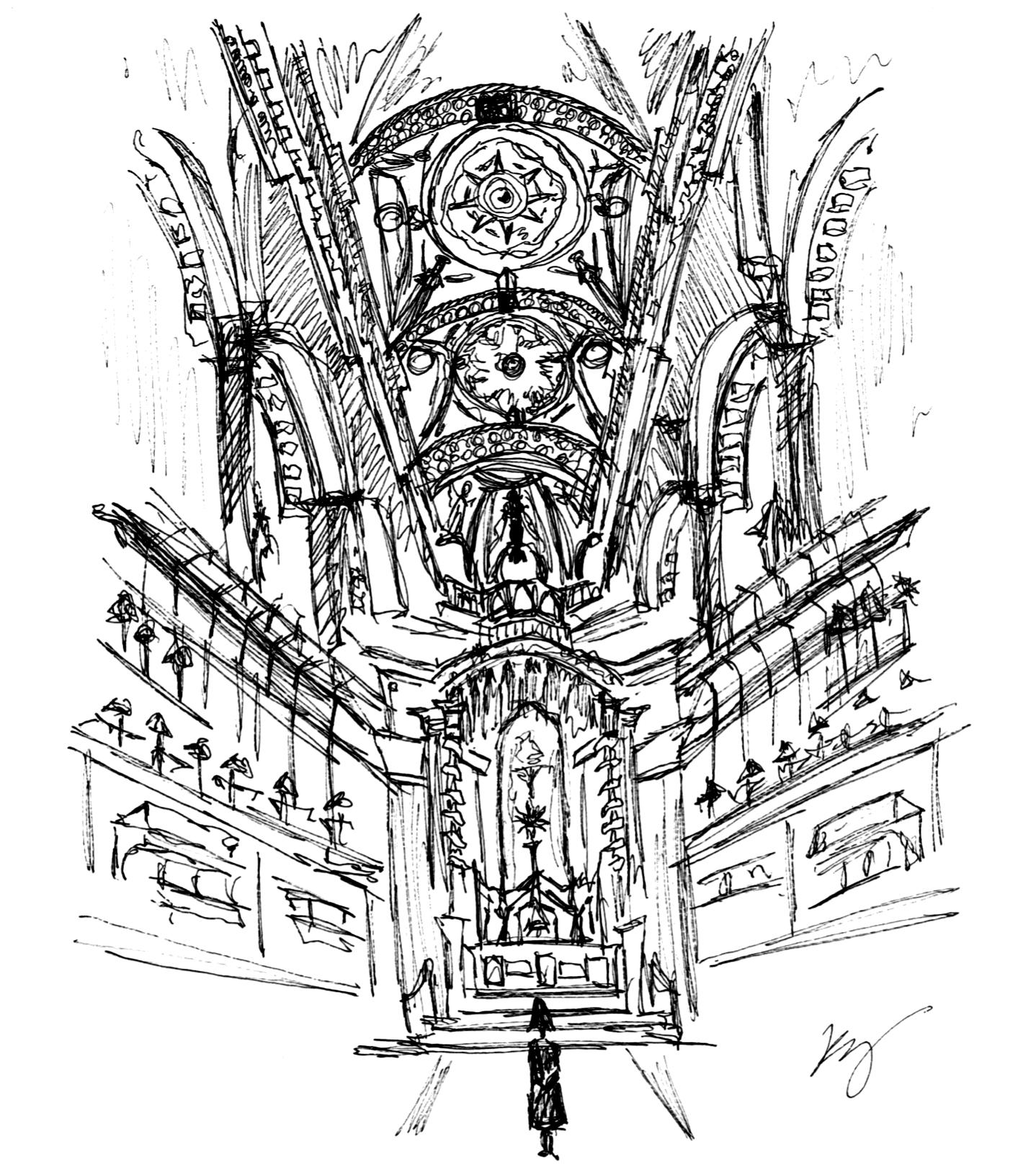

The spectacle of the church overwhelms me; looking up at the white columns and arches rising above makes me dizzy. I rush inside because the music has already started. I’m accompanied by two older women who hurry to get their programs and find a seat together. I wonder if they’re church friends, if they come here together every Sunday. I take a seat and look up at the central dome, where light pours in through a small opening. A bird flies through the central dome and through the nave, pacing along the painted walls and escaping to the outside air. A few minutes after I take my seat, a man holding his son’s hand walks in and takes the seat to my right. The man helps his son into his seat and whispers something in his ear. He hands him a toy truck.

At home, I go to Compline services on Sunday nights, when the space is only lit by candles. A chorus in an invisible loft sings and their voices spread through the church, made anonymous by the darkness. Even though you can hardly see the person sitting next to you, you feel the sense of togetherness more intensely.

I don’t know what it is, the voice of the minister who has started to speak or the father and son talking softly next to me or that I’ve come alone to this space filled with people, but I feel my eyes fill up with tears.

It’s when the minister says, “As Christians, we must know what we want” that I begin to really feel the words and the music and the smells affect me. He tells a story about going to the ocean with his family in North Wales as a child and feeling afraid of the rain and the waves. His mother told him to pull his coat farther over his eyes and to hold her hand. Her words, he says, gave him a sense of direction.

The question “what do you want?” has always freaked me out. I think at many decision-making junctures, I’ve wished for someone to step in and answer for me. I want to hold a friend’s hand and to be told to pull my rain jacket over my head. I’ve wanted to hand the microphone over and listen to what someone else has to say and nod along.

I think about what makes me feel lost, and what gives me a sense of direction. Looking around at the little signs of intimacy between strangers — the children who share glances while singing, the volunteer who guides latecomers to their seats, the friends who whisper to each other between songs, the woman who touches her husband’s hand while turning a page — I think about the relationships in my own life that give me direction.

The minister continues: “God gave us hands and feet and eyes so that we could do his work. So that we could get dirty in the process of loving each other.” The cavernous space within the cathedral turns each syllable and sound into a booming wave, so that each new word is carried by the one before it. At first, this line made me smile: I imagined the minister inviting everyone in the cathedral to roll up their sleeves and throw handfuls of mud at each other. But as he moves onto his next point, I think more carefully about what he means.

I spend so many moments throughout the day rehearsing what I hear and what I say in my head: Does he think I’m funny? Did she understand what I was trying to say? Holding his hand while walking home last night made my stomach do little backflips, but will he really text me tomorrow? Can she tell when I’m feeling upset, withdrawn? Listening to the minister, I’m realizing that maybe these questions are part of the “getting dirty” in loving each other. But these day to day worries feel so trivial, so small in this huge space, and my mind goes quiet.

I think about the note a friend wrote in the inside-front-cover of the book he got me for my birthday. The jokes that my brothers and I crack across the dinner table, or on road trips. The “night runs” that my friend and I go on for hours around the neighborhood, running until we need to walk and then starting to run again. This room full of people who are observing, but participating in this celebration, the minute signs of love found every second, constantly. To love is to know what you want, to love is to have a sense of direction, to know where you’re going. And then the bells start ringing and we all go outside again.

Annie Nields | annie.nields@yale.edu .