Danie Zhao

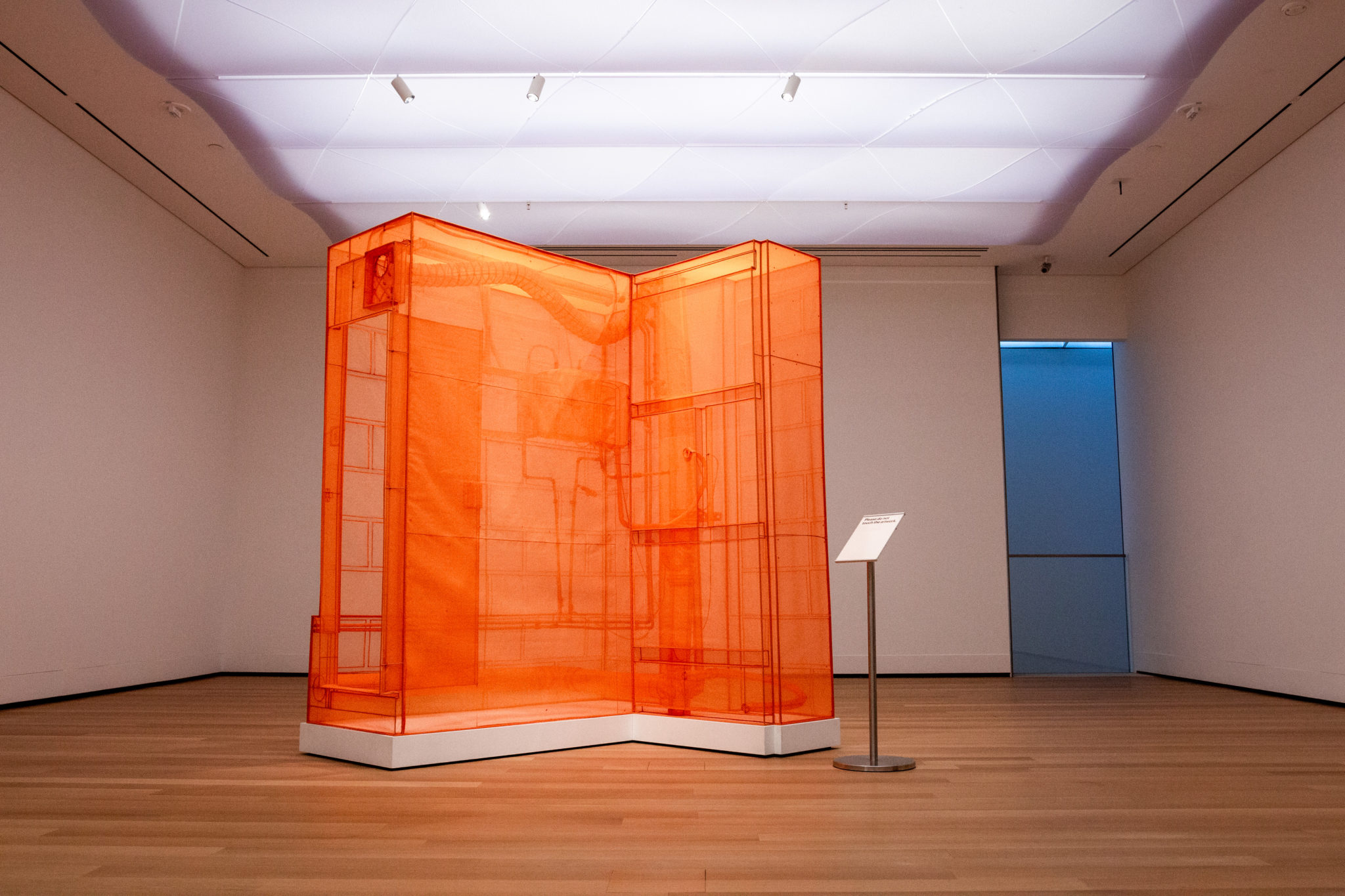

Orange, strong and monochrome, stares me in the eye in direct conflict with an otherwise empty room with blank white walls and wood floors. Light penetrates the layers of translucent orange fabric comprising the life-size structure. Hand-sewn details define the orange outlines of a light switch, water pipes and a door.

I stare back at the sculpture, carefully crafted from polyester fabric and stainless-steel tubes by South Korean artist Do Ho Suh ART ’97 in 2015. The work, titled “Boiler Room, London Studio,” stands alone in its space in the Jane and Richard Levin Study Gallery on the fourth floor mezzanine of the Yale University Art Gallery. A video titled “Rubbing / Loving” and short description of the artist and his work accompany the sculpture.

A security guard told me that visitors to the museum often enter the room expecting an entire exhibit and either turn away uninterested or take two or three minutes to walk a slow lap around the small room and then leave. I continued staring for a few more minutes than average, mesmerized by the layers of orange that appeared darker in denser areas and lighter in areas with fewer stitches. With one color Suh created a multi-dimensional object — the more I stared, the more layers seemed to appear underneath the mesh-like walls of the boiler room.

After earning undergraduate and graduate degrees from Seoul National University and a B.F.A. from the Rhode Island School of Design, Suh shifted his focus from painting to sculpting — specifically, sculpting with cloth.

The sculpture is characteristic of Suh’s series of “fabric architecture” pieces. The exhibit’s description typifies it as “soft when it should be hard, transparent rather than opaque, light and portable as opposed to heavy and stationary.”

In creating those sculptures, Suh combines his painting background, traditional Korean sewing techniques and three-dimensional modeling technologies. One of his goals is to create surfaces and edges as thin as possible to encourage the transmission of light.

The accompanying video discusses Suh’s relationship with space and human memory, explaining the motivation behind his recreation of living spaces through another of his works, titled “Rubbing/Loving.” In it, Suh covered every surface of his New York apartment with paper and rubbed it with colored pencil to “preserve all of the space’s memory-provoking details,” according to the video’s description. The soft purples, faded oranges and bright yellows of the pencil highlight the outlines of every brick, tile and crack in the space, and are darker in the corners to show human wear on the apartment. When the paper is removed from the apartment, it retains the building’s original shape: another skeletal recreation of place.

Suh compares the Korean word for “rubbing” with an alternate translation: “loving.” Is this how Suh shows love — through his memories, through imprints of places?

We often live in spaces without ever thinking about them, and our memories of a space often remain in the space when we leave. Suh’s sculpture defies our connection between place and memory because of our ability to take his sculptures apart and reassemble them in an arbitrary location in ways the physical rooms cannot. Through his recreations I imagine that we physically move our memories around.

The L-shaped pieces of orange fabric sewn together in “Boiler Room, London Studio” appear fragile yet permanent. I’m drawn to four perfectly sewn letters spelling the word “fuse” upside down. Fuses operate to prevent too much “current” in a circuit. And while we are often encouraged to think in the now — the “current,” this sculpture reminds me not to forget about the past — to prevent too much “current” in our lives. I think Suh wants to forever fuse the physical boiler room with his experiences living there.

I’m fascinated by being able to walk around a ghostlike recreation of a space where the walls cave to the touch of a pinky finger and there’s no one inside — no one can be inside. Suh’s art explores how we perceive our living spaces, and “Boiler Room, London Studio” removes us from the space and inspires a viewer to see how we relate to the places we inhabit isolated from our interaction with them.

Through his fabric recreations — fabric-ations — of places, Suh freezes the passage of time, pausing the process by which humans alter a space and holding how we remember it in our memory. I find that I do not even remember the layout of the house I lived in as a child less than ten years ago, and my inability to access that lost memory scares me.

Suh’s sculpture will be on display until Dec. 8.

Phoebe Liu | phoebeliu@yale.edu .