Valerie Navarette

It has been 30 years since I wrote my last column for the News (March, 1989: “It is time to legalize drugs in the City of New Haven”). My 30th reunion provides an opportunity for this one-time denizen of Formerly Known as Calhoun College to comment on the 2017 decision by Yale to rename Calhoun as Grace Hopper college, which has prompted everything from sober reflection to heated ranting.

While criticism of the Yale administration for the somewhat halting process to adopt the name change was warranted, the report that the Committee to Establish Principles on Renaming (CEPR) issued presented a model of the kind of even-handed, thoughtful discourse so woefully lacking in today’s political culture. It was a welcome echo of the 1975 Woodward Report that set the standard for the defense of free speech on college campuses, which seems to have increasingly lost its influence today (including, sadly, at Yale itself).

A recurring criticism of the decision to rename Calhoun is that it uses a double standard: the sins of Calhoun are allegedly no worse than of other slaveholders whose names figure prominently on campus, including Elihu Yale himself. This whitewash of history, it is claimed, picks Calhoun as a convenient target to assuage liberal guilt, ignoring complex historical realities and overlooking Calhoun’s achievements as a statesman and political theorist.

Is it reasonable to single out one dead white man for our collective ire when so many others whose names adorn great institutions have their own sins to bear? Or has the conservative backlash against political correctness become so all-consuming in today’s polarized culture that it fails to distinguish between left-wing snowflakism, and a reasoned examination of whether the symbolism a name carries is consistent with Yale’s values?

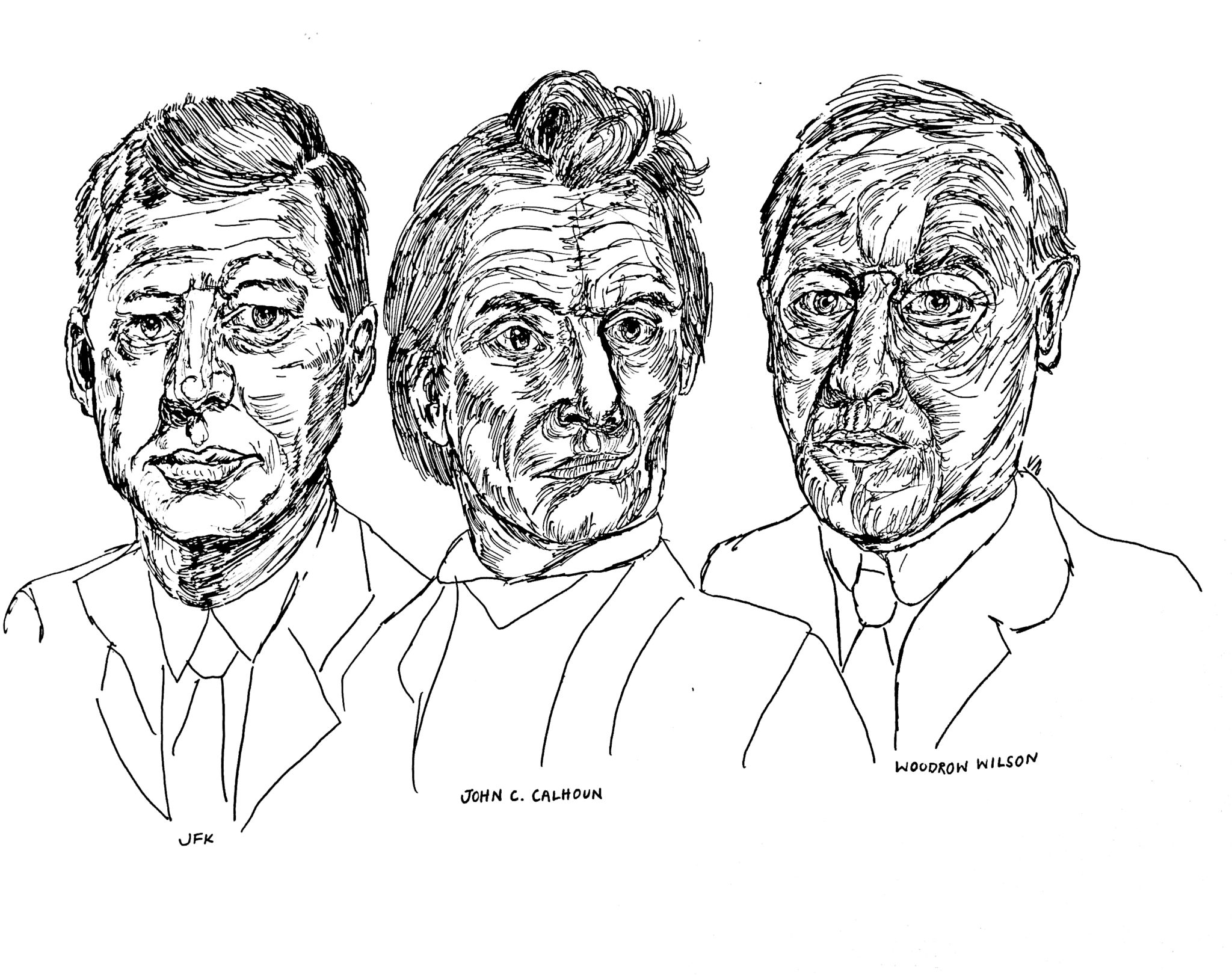

In evaluating the merits of changing an institution’s name, I suggest it is reasonable to adopt a kind of “Wikipedia test” to see how a historical figure’s defining qualities are remembered in the first few lines of his or her Wikipedia entry. To illustrate, compare the entries for John C. Calhoun and Woodrow Wilson, another controversial figure whose embrace of racist theories and policies prompted demands that his name be removed from a school at Princeton.

For Wilson, Wikipedia highlights his positive achievements — serving as President of the United States, Governor of New Jersey, sponsor of progressive legislative policies, and some lesser accomplishments (President of Princeton). His racism and actions to remove African Americans from the civil service while President deserve condemnation, but these are not what primarily define him for posterity.

Calhoun, by contrast, is described by Wikipedia as a statesman who strongly defended slavery and “Southern values.” He is remembered first and foremost for being not only an apologist for slavery, but also an active defender of it as a positive good.

No less a liberal icon than John F. Kennedy called Calhoun “a masterful defender of the rights of a political minority against the dangers of an unchecked majority” when he named him one of the five greatest U.S. Senators. But even if you believe in the importance of the political rights of minorities (as I do), to the extent that Calhoun’s defense of such rights was primarily driven by his desire to maintain slavery, holding up Calhoun as a statesman worthy of commemoration is deeply problematic.

This “Wikipedia test” falls short of the CEPR’s charge that the University “study and make a scholarly judgment on how the namesake’s legacies should be understood” but is a valid way to consider how contemporary society measures a figure’s essential historical relevance against its values.

Too easily have conservative critics of Calhoun College’s renaming hurled charges at Yale’s administration of succumbing to political correctness. While criticisms of the tyranny of political correctness have been all too valid in many other contexts (notably in Yale’s sorry handling of l’affaire Christakis), the case of Calhoun is fundamentally different than that of Wilson and other historical figures whose names grace buildings at Yale.

The failure of conservative critics to make this distinction weakens their argument both in this case and in others where such charges are on firmer ground. And the failure of liberals to distinguish between the likes of Calhoun and other dead white male slaveholders whose relevance to posterity is not defined by slave ownership simply drives their political opponents to adopt more extreme positions in reaction, escalating the cycle of polarization.

I will forever think of myself as a “Hounie,” even if of the “f/k/a” variety. But I can hold onto a sentimental identity formed 30 years ago, and at the same time acknowledge the validity of the decision that it was time for the Calhoun name to go.

Arthur Rubin ’89 works in Latin American finance in New York City and is the former Chairman of the Yale College Republicans. He can be contacted at arthur.rubin@aya.yale.edu.