Editors’ Note: This piece originally appeared in the 2019 Commencement Issue, published on May 20, 2019.

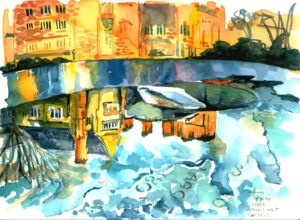

In September, my art class draws the Women’s Table for our first meeting. Though we share a subject, we all depict a different view: a zoomed-in crop of the surface texture, the full table ringed by easels, the junction of rounded edge and sharp corner. I pick the surface: Berkeley College and one easel are reflected upside down in a tablecloth of flowing water.

A month later, I receive an email from our professor. The Women’s Table is strewn with flowers from the Solidarity with Survivors vigil the night before; we should go look at it and contemplate how monuments remain relevant. I revisit the table the next morning. Flowers lie on the table, their petals wilting in the humidity. Sticky notes adorn the base, bright splotches of color. “You are heard, you are loved,” the Women’s Table says.

I return to the table multiple times during senior year and watch it change as the days grow shorter and then longer. I see toddlers play by it. Tourists snap photos. Students rush past.

In my four years here, an idea I find myself returning to — particularly in times of conflict — is that people can be multiple things at once, but it is easier to box them into one contemptible thing. Condescension is the new persecution. I used to think about this idea in terms of Sandra Cisneros’s onion analogy: People are constructed of concentric layers. We don’t see them all, because they exist at different times. An instantaneous, one-dimensional view is easier to understand.

These days, I think about the Women’s Table. I scrawl on the back of my vigil sketch that the Women’s Table remains relevant because it reflects and encourages reflection and captures nuance for all who look at it. Its surface reflects its surroundings as they change — the physical but also the social. The Women’s Table is home to a toddler squealing in front of the castle-like libraries just as it is home to mourners, activists and passersby. No matter who stands before it, it absorbs and reflects that moment in its entirety.

People ask me how I feel about graduation, but instead of feelings, I have memories. Reflections, of sorts.

I remember an interactive music exhibit at The Tech Museum in my hometown, San Jose. One of the stations consisted of a touchscreen panel that, when poked, generated brightly-colored expanding rings. As the rings collided, pitches sounded, then reverberated. It produced a cacophony of color and tone, mesmerizing, but also jarring. This is what it is like to leave a place. Our lives touch for a moment and then push apart. Sometimes the reverberation is pleasant. Sometimes it is painful.

I remember my sister’s graduation from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2017. Seated beneath the blinding sun, I listened to President Rafael Reif implore the future graduates to use science and technology to make the world a better place. The sentiment is similar here: We are encouraged to become leaders and use our Yale education to improve the world.

I remember writing in my college applications four years ago, “When I see conflict, I see people unable to understand each other.” Back then, I naively thought that, with empathy, we could simply shed our skins and wear someone else’s. But I also wrote — now, an odd foreshadow to this essay — that we needed to “see another perspective.”

I think the question is not how to make the world a better place but how to reveal its nuance. How to trade a black-and-white vision for a colored one, how to turn a moment of one-dimensionality into a time-lapse of perspectives, how to embrace the cacophony over the singular.

When our rings touch, how do we reflect others back as they are, in all their layers and incongruencies? How can we transcend a mentality that reduces us into victims or scapegoats? In the stories we tell and consume, how do we frame the people whose voices we hold? Do we linger, as the Women’s Table does, past the moment of impact, the sensationalist headline, the popular movement? Beyond simply hearing, do we listen to the reverberation? Will we let it color our vision, change our minds?

If you stood at the touch screen panel, the collisions shifted from contained to a jumble of interactions. If you stayed and listened, you could make out faint chords among the dissonance, but there was no singular key. And if you looked long enough, the rings began to resemble colorful, deconstructed layers of an onion.

At the end of that first art class in September, I walked around the easels and saw the Women’s Table everyone else saw. You did not have to paint the same view, or in the same style, to see another perspective. You just had to look. Seeing the world exactly as it is requires time. It requires us to let go of certainty and ask more — to constantly collect and absorb a cacophony.

To make the world a better place is one aspiration. To be a better person in the world is another. But to do either, we must first better see the people in the world. The richness of that cacophony allows us to eventually see every shade of every color, all at once. To be a monument, in the present, for the future.

Sonia Ruiz is a senior in Grace Hopper College and a former Illustrations editor for the News. Contact her at sonia.ruiz@yale.edu .