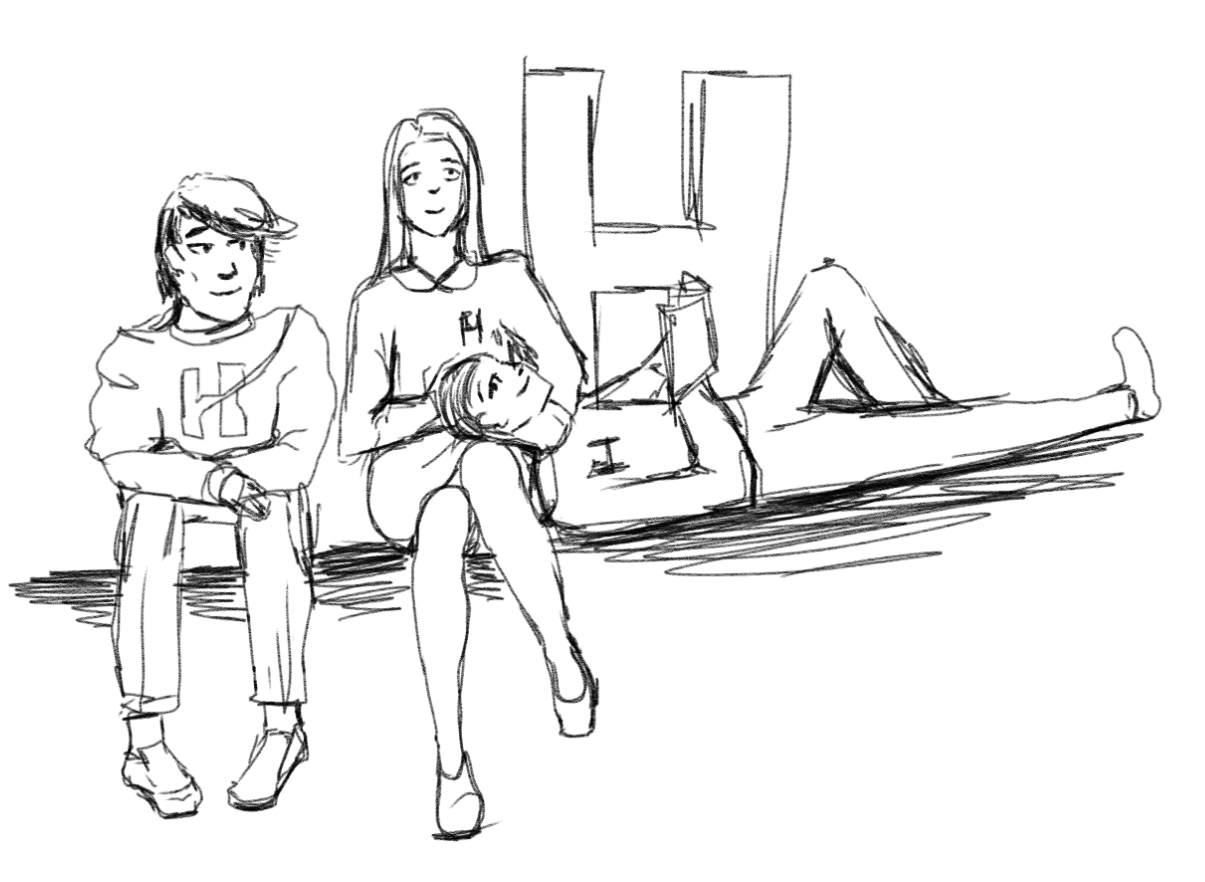

The acceptance letter is enclosed in a glossy red folder, the kind that shows sweat marks when you take your thumbs off. There’s a picture on the front, a group of friends cross-legged on a mowed lawn, laughing together. They’re all wearing bright red Hannity Prep sweatshirts, the crests on each crumpled a little where their bodies fold over; one boy rests his head on a girl’s knees, and his hand on his stomach covers the stars that outline the lion. They’re all getting grass stains on the sweatshirts, Maggie can tell. That means they have more in their closets, probably. Probably they wear them every day. Maggie would. Maggie will. Maggie could strip off her collared dress right now, in the third floor bathroom, could throw it out the window or hang it like a flag. She doesn’t. But she could. She almost wants to. She wants to draw the kids on the folder, until the wanting feels like something real.

There’s a blonde girl in the picture who looks a bit like her, only this girl has dimples, and she looks older than 15, maybe. When the girl smiles it looks like someone punctured her face so she could hold all that happiness without bursting. Maggie learned a new word from “Macbeth” recently: incarnadine. To make something red, to be red, pinkish-red, like skin just before it bleeds, when the heat rushes up. That’s what Hannity’s like. Incarnadine. Always proving it’s more alive than everywhere else.

But Hannity should stop making their folders so bright; it’s not fair, it makes them harder to hide. It’s a miracle Maggie managed to intercept it at all. Mom insists that they run The Season the same way in the winter that they always do, which means that most of Maggie’s school break is spent trailing a Swiffer across Victorian furniture, moving old photographs around until they look like they’ve been there since the inception of everything. The Season is open year-round, but no one ever stays in December. Maggie can’t remember a single time when they did. Mom still serves breakfast at 8:30 every morning, though, always orange juice and donuts and grapefruit. Enough Vitamin C to numb your mouth and enough sugar to sustain you on the beach, she always says, and it’s a beautiful day, and every day in Foxbury is a beach day, and that stays year-round, she says, that stays. Maggie thinks Maine is like a suction cup in the winter, stealing color; even the ocean looks faint.

The Season’s slogan is “The B&B Where Time Stands Still.” Mom spends most of her time making it true. Maggie spends most of her time agreeing that it is, even when she’s smuggling bright red folders under chunky brown dresses and trying not to break the quiet, to seem too giddy, too incarnadine.

***

Every Sunday, she and Mom drive around Foxbury in the Chevy, running errands for the week. In the summer, this means going to the laundromat to wash towels, renewing beach passes, checking the post office for magazine subscriptions, refreshing The Season’s brochures. In the off-season, they negotiate winter prices with local merchants, for things like orange juice and donuts and grapefruit. When David — Dad — was around, The Season shut down in the winter, but the three of them would still drive around like this, getting donuts only for themselves, whatever kind they wanted. The women at Willie’s Bakery loved him. He used to hum as he walked in, purposely off-key, some Rolling Stones song Maggie can’t remember the name of. The women at the bakery don’t love Mom, even though she hums the same song and smiles, and even though they know she was once David’s wife, before David left with Annie for Prague. She was once David’s girlfriend, too, before Annie was. Before anyone was.

Maggie used to wonder why David and Mom ever married at all; he was so loud, and his voice echoed through the whole house. Guests used to tell him they’d woken up because of his singing, but they never minded. He was good at managing the house, because it used to be his family home, generations of Gallaghans living and dying in the same rooms, a trajectory even a toddler could trace. Mom was never good at running The Season, not decorating or cooking or talking to guests, but she loved it more than any of them. She used to say, to anyone who would listen: This place is more David than David is. Maggie doesn’t know what it is now, because it couldn’t have been that, or he wouldn’t have left.

“How many donuts we need?” Mom asks Maggie now, parking in front of Willie’s.

“A dozen, maybe? If it’s just us.”

“You never know,” Mom says, as she’s been saying for three years, ever since David left and The Season became a year-round occupation. “What kind should I get?”

“I don’t know. You pick.”

“You always pick.”

“Whatever you want is fine. Same with the bagels. Whatever you want.”

After Mom leaves, Maggie turns the car’s heat off and rolls down her window, the way Mom hates, waiting for the wind to make her face tingle until she can’t stand the sting. Her eyes burn from the effort of keeping them open, and she begins to count to see how long she can last before blinking. Ten seconds. Fourteen. She watches kids pass, most of them her classmates from Foxbury High. One particularly large group emerges from the diner across the street, all nearly identical in their black fur jackets. They look nothing like the Hannity picture, their mouths firmly shut, squinting against the wind. But one of them stands differently, more upright maybe. Or maybe it’s just that Maggie could spot Kelly Owen from a mile away, her red hair peeking out from her hood, her nose pink from the cold. Her freckles look like snow that decided it couldn’t sting someone who looked like that, so it just landed instead.

Maggie doesn’t really know Kelly Owen, because Maggie doesn’t know most Foxbury students, even though she’s always lived here. She tries to be nice — most kids can’t get past the dresses she wears. But one day last month, Maggie and Kelly Owen were in the girl’s bathroom at the same time, Maggie washing her hands, Kelly Owen applying red lipstick, and Kelly Owen said, “Why do you dress like that?”

“What do you mean?”

“Like that. Like an old lady. Do you want to, or does your Mom dress you?”

Maggie just stared at her through the dirt-spattered mirror; she was watching the way Kelly’s widow’s peak sat evenly between her eyes, how her lips turned inward the same way, how she never would have thought to draw something like that if she hadn’t seen it herself.

“I don’t know,” Maggie answered finally, after Kelly lifted her right eyebrow.

“It’s not a trick question. You don’t know what you want?” she asked, rolling her eyes. Her eyes were green, but not like grass. Maggie couldn’t think of a word for them. She sometimes thought high school was an attempt to pretend you could find the words for anything, because some words were never quite right and in a place like this, surrounded by graffiti on toilet stalls, you weren’t allowed to admit it. It was as though she’d finished a carton of ice cream and discovered it was boiling hot the whole time, sloshing and curling only once it reached her stomach. She didn’t say anything, just watched Kelly purse her lips, thinking of a word that would describe them. When Kelly finally left the bathroom, her eyebrows furrowed, Maggie drew her in her AP U.S. History notebook, on top of her notes about the Treaty of Paris.

Ms. Degarsy, her guidance counselor, called Maggie into her office only a week after. Maggie had thought it would be a meeting about how she shouldn’t draw her classmates during lunch period. She was ready to tell Ms. Degarsy that this was how you made time stand still. She wanted to tell her that she was going to frame Kelly Owen against the bleachers like a Greek statue, the whole school crumbled around her. She sat in the guidance office, fingers stained with ink, wanting Ms. Degarsy to ask what her drawings looked like so badly the wanting didn’t feel like anything, so she couldn’t tell Kelly Owen about it.

But instead, Ms. Degarsy asked her, “I’ve been talking to your teachers about your performance. Did your mother ever consider transferring you to private school? Somewhere like Exeter, or Hannity?” She passed Maggie a brochure that had been facing away from her on the desk. On the front was a photo of friends, laughing; Maggie realized at a glance that it didn’t fit the rule of thirds. There was something illicit about it. She watched the blonde girl’s dimple, almost horrified, like it was marble that had been smashed in. She wanted to touch it, to see if it would cut. It was a stupid want, but she wanted it.

“Now, Foxbury is the one who pays me. But this is a place designed for students of your caliber, and I have the utmost confidence you would excel,” said Ms. Degasy. “I don’t think you want to stay in Foxbury forever, do you, Maggie?” said Ms. Degarsy. “You want to grow,” said Ms. Degarsy.

Maggie thought of Kelly Owen, and how she didn’t know whether she wanted to wear Mom’s old dresses. “Yes,” said Maggie, which wasn’t quite the right response. Maggie looked down at the brochure again. Something about it made her stomach clench slightly, like it used to before she and David would go on a roller coaster at Six Flags, and David would say, Are you ready for it, never specifying what It was. It was the red, maybe. It was the kids, laughing about nothing. There was something alluring about even the way “Hannity” sounded, how the word dipped down in the middle and then found its way back up again. She touched the edge of the blonde girl’s dimple, creasing the paper with her fingernails. She could feel Ms. Degarsy watching her. There was no mention of the drawings.

Now Maggie has two things she can’t tell Mom about. She wasn’t supposed to be drawing Kelly Owen, because Mom wanted her to paint a mural of The Great Exhibition for Room 301, and Maggie said she’d show her sketches this week. Mom loves The Great Exhibition, because people say it was the beginning of everything, but really it was just before everything began. A moment of absolute stasis. Time didn’t even stand still; time barely existed.

Mom would never have stopped Maggie from applying to Hannity, Maggie knows, because Mom would never stop her from doing anything, not wearing lipstick or drinking the mash bill whiskey in the basement or touching Kelly Owen’s hair — not even that. After all, Mom didn’t stop David from leaving; she didn’t even try. But she might get bad again, if she knew Maggie wanted to leave, bad like that first Christmas without him, screaming at everything. All Maggie will be able to show her is red hair, and a folder, and she won’t have the words for either.

When Mom returns to the car, she hands the donut box to Maggie carefully, as though there’s something fragile inside.

“Since you didn’t tell me what kind you wanted, I just got the usual,” Mom says, patting her pockets in search of her keys.

“Three glazed, three chocolate frosted, three chocolate glazed, three plain,” Maggie recites, a litany. She checks the receipt — no discount. The credit card Mom uses is still under David’s name. It’s only when Maggie’s fingernails dig into the “David” that she realizes her hands are shaking. Mom notices and frowns at the open window.

“You’re going to get sick, darling,” she says. “Darling” used to be her nickname for David. Before, Maggie was always “honey,” or “peaches.”

“I won’t get sick.”

But Mom rolls the window up from her side, and she turns the heat back on full blast. Maggie doesn’t argue, because they’ve been here before. They got the same donuts last week, and only finished half. Maggie watches as the foggy window skates along Kelly Owen’s body, like it’s trying to wake her up.

***

When they get home, Mom ushers Maggie into the dining room, insisting she show her something.

“I found this footstool the other day, look. For the third floor.” She gestures to a small red-velvet object with gold tassels, embroidered with purple thread. Maggie thinks that it’s ugly, but that’s never the point with Mom. It looks like something out of a movie, the kind Mom used to make her and David watch, some black-and-white romance. And in those movies, you never see the color of anything, you just imagine, and the truth is that a lot of everything probably looked like this, red and purple and ugly. But Mom’s smiling, flushed around her cheeks, her lips parted. She hardly ever looks like that anymore.

“We don’t need a footstool,” Maggie says, wanting to mar Mom’s smile without knowing why, “we have so many. They all look kind of like that, too.”

“This can replace one,” Mom says, waving a hand. “Circle of life.”

Maggie hums the song from The Lion King under her breath, still staring at the footstool. Mom laughs, delighted.

“You’re just like Davey,” she says. She grabs a Swiffer from where it had been leaning against the mahogany table and begins to scrub at the floor, humming the Rolling Stones song, her mouth settled in a half smile. Maggie remembers the way she looked the Christmas after David left, yelling his own words into the tree, paper ripped, face flushed. Calling Maggie “darling,” saying she looked just like her father, saying she hoped they would both leave, because she knew they wanted to.

David and Mom made The Season together. They took a crumbling family home and covered it in floral wallpaper. They wrote up a fake history for the brochures, to make the operation of the place seem older than time itself. It was started by Mr. and Mrs. Gallaghan during the American Revolution, the legend went, and served as a respite for war-torn soldiers and their families. It had seen more of history than history had, David would say, and Mom would say, that’s why the plumbing is bad, it’s cantankerous, and Maggie would repeat “cantankerous” under her breath, committing the word to memory. But when David left he didn’t want that history anymore. So the house kept it. They still use the same brochures.

In the summer, there are children pacing between rooms, parents slathering sunscreen onto their backs. Now in the winter, there’s just waiting for David to call, waiting for Mom to lose it like that first Christmas, half hoping she will just so the quiet will end. Maggie remembers the shredded wrapping paper, remembers wondering if Mom will die in this house, not even that day, but someday, or if her screams will cause a burst in the pipes she worries about maintaining. Mom hasn’t screamed since. Maybe she’s afraid that if she does, she’ll never stop.

“Do you want to visit David and Annie for Christmas this year?” Mom asks now, staring at the Swiffer as she moves it back and forth. She’s asked every year.

“I don’t want to visit them.”

“You can, though. You should. I can help you, I can book your flight.”

“I don’t want to.”

“You don’t have to be here during the winter. I’d understand. It gets dark here, but what can you do? You should go. I’m not going to go, but you should.”

They’ve been here before, so Maggie says, “I want to stay here. It’s quiet,” and Mom looks up at her and smiles. That’s all it ever takes to appease her, a simple version of the truth, that Maggie is as afraid of loud noises as she is, that Maggie isn’t David, that Maggie also worries the pipes will burst. Maggie doesn’t say that she wishes they would, so she can stop thinking about it. It’s not quite the truth, not quite right, but it touches it.

***

The third floor is the only part of the house that looks like a house, not The Season. There are boxes strewn everywhere this time of year, filled with old paintings that used to hang on the wall, with Maggie’s school supplies from third grade, with tax forms hidden behind photographs of an old Pennsylvania circus. The toilet doesn’t work, but there are still fresh hand towels in the bathroom. Maggie can never tell the difference between the paintings Mom takes down and their replacements. She hides the Hannity folder behind one of them now, a still life of an apple, a banana and a peach.

When David left, the third floor became a project, the rooms an open invitation to stay busy. Mom finds footstools and frames old photographs. She asks Maggie to paint murals, and she buys lace bedspreads. A few days after David left, Mom turned his old prom tuxedo into a pillow; Maggie found her in the hall on her knees, hitting the sewing machine to make it go faster. That pillow waits in Room 301, a glaring anachronism.

Maggie doesn’t know why David left, not the full story, only what he told her when he chose to tell her anything, an easy story about how he and Mom married young, and how they wanted different things. He didn’t mention that he was the only one wanting. Maggie thought, sometimes, that Mom had always expected him to go, and that she’d always been ready to choose the David that lived in the house, the David who was more David than David was.

“You should go,” Mom once said in the middle of the night, loud enough that Maggie could hear. “This place is what it is! What can you do?”

“It’s dead,” David said, quieter. Maggie could hear him anyway. “It’s a dead place, Mom and Dad died here, do you want to die here? In Foxbury? What the fuck are we doing, raising her in a haunted house? What kind of childhood is that?”

“It’s a safe one! You had a safe one here, David. You are this place. This is Mr. and Mrs. Gallaghan, this is— ”

“You know that’s not true, you know none of that is true. You know that.”

Maggie was 12. She couldn’t have named what she wanted at the time if Kelly Owen had asked, but it was loud. She has a notebook full of drawings from those months, drawings of Dad packing, neat portraits. It’s stashed somewhere on this floor. Those portraits were time standing still, and they’re so fraudulent they’re almost comical. Maggie doesn’t want to wear these dresses. Maggie doesn’t want to freeze time. Maggie wants to draw Kelly Owen with her mouth open, laughing. Maggie wants to go to Hannity. Maggie wants to hang all the paintings in the house, new and discarded, next to each other, until she finds a difference between them, even though she knows none exists.

***

When Maggie returns downstairs, she finds Mom in the parlor on the old landline phone, surrounded by boxes, punching in numbers. Every few seconds, a beep will sound, and she’ll hang up and redial. When she sees Maggie, she sets the phone down; Maggie can hear you are on hold. Your call is very important to us. Thank you for your patience… play against elevator music, muffled.

“Do you know,” Mom says, “the amount of extra vegetables I have in the fridge? I always forget to order less this time of year. You should eat them. You should bring a friend here, and you guys can make a salad.” Maggie imagines inviting Kelly Owen to eat salad in the kitchen, with its granite island.

Now is the time to say: Mom, I’m leaving. Or: Mom, your call is very important to us, you are very important to me and the pipes in this house are going to burst. Or: Mom, I want to wear red lipstick, I want to incarnadine, I didn’t know that’s something I could do. Mom, thank you for your patience, I think we should stop waiting, I think no one is coming to eat the vegetables.

But before she can say anything, Mom says, “I want to redo the brochures.” She hands Maggie one of them, as though Maggie didn’t grow up hearing about Mr. and Mrs. Gallaghan, and the war, and history before history.

“What do you mean?”

“I want a new story. I think the reason we don’t see as many guests here in the winter is that the story doesn’t work anymore. It’s outdated.” She gestures to the boxes. “We can use these pictures.” Maggie opens one of them to find an old family photo album from when she was a baby; the front cover is a picture of Mom, David and some swaddled thing, a tuft of blonde hair covering her eyes. She flips through. Maggie at Disney World. David cooking eggs in the kitchen, before it had granite. David and Mom at their wedding. David and Mom in high school, David in his Foxbury High football uniform, Mom in a long skirt, shying away from the camera, looking frightened.

“We can’t use these pictures,” Maggie says.

“The problem,” Mom says, “is that right now, we’re not telling a family story. We’re telling a war story. It should be a story about our family. You’re practically grown-up now — it should be about all of us.”

“Not this family. This isn’t — we can’t advertise this, because it’s not true.” The words aren’t right. But Mom doesn’t even blink, just nods, as though Maggie is making an argument she’s heard a thousand times before, as though she’s never screamed obscenities into the Christmas tree, as though she’s ever wanted anything that’s real.

“That doesn’t matter,” she says. “When Davey and I wrote about Mr. and Mrs. Gallaghan it wasn’t true. People know it’s not true. They just like the story.”

“I think people don’t like the story, because it’s not true. I think we don’t need a story at all. We don’t need to be open in the winter. No one’s coming.”

“Do you want to leave?” Mom says, as she always does. “You can visit Davey. It gets dark. But it’s good for us, to stay open. There are always people who might stop by.”

Now is the time to say: I’m leaving, Mom, but not for Prague. Now is the time to say: Mom, you should put on lipstick. Now is the time to say: Hannity’s off-season is the summer, and in the summer, things can grow. She doesn’t say anything. But she wants to. She wants the pipes to burst. She wants to kiss Kelly Owen. She wants to call David “Dad” again, she wants him to come back. It’s stupid, they’re stupid wants, but at least she wants them.

She runs up to the third floor. She grabs the Hannity folder from behind the painting. She grabs her old notebooks too, the ones with Dad in them, and she takes her new one from where she keeps it in the bathroom. When she returns to the parlor, Mom’s still on the phone.

Maggie opens the folder, to show the acceptance. She opens the old notebook, to show Dad as he was leaving, a lifelike rendering. She opens the new one, to show Kelly Owen, the sketches growing more and more frantic as she turns the pages. She says nothing, there are no words that are right. She wants Mom to understand anyway. She wants to ruin that tranquil expression that remains fixed on her face, wants her to scream, like she did before. She wants it so badly the wanting feels like it will kill them both. The house is so quiet. Mom says nothing, just looks at Maggie and smiles.

“Congratulations, darling,” she says. “You should go. I’ll help you book a flight for a tour.” The elevator music keeps playing.

You are on hold. You are on hold. You are on hold.

Maggie says: “Can you just hang up, please?”

Mom says: “Give it a moment.”

Maggie says: “What are you even calling about?”

Mom says: “I’m ordering more vegetables.”

***

Maggie begins the mural that night. She starts with a pencil, drawing the outline of the Crystal Palace, the way it looks in her history textbook, all straight lines and easy curves. Once she begins to sketch the windows, she imagines the neatness of the image, how false it’ll be. She grabs the cans of paint under the bed instead and begins to trace a face in red, larger than life, over the roof of the building. At first, she thinks it’s Kelly Owen. By the time she reaches the chin, though, she knows it’s Mom, and she paints her as though she’s screaming, or smiling, face flushed, lips open. She paints her hair blue, dresses her in a long green gown, splatters yellow behind her, a swirl of yellow, then purple, then every color she has, a whole rainbow, and Mom in the middle of it, screaming, smiling, wanting. Then she throws the can of red paint over it all. The can crashes to the floor, paint dripping onto the hardwood. When she turns around, she notices that red has dripped onto the pillow Mom made, small drops on the edge of the tuxedo. Maggie runs her hands over it. Red, everything red, everything real.

She wants to laugh. So she does. She can feel the house around her, stifling the sound.