Ms. Blok wears see-through, cream-colored shirts to school every day. Her bra today is dark purple, clearly a size too small for her, and her fleshy back crumples where it rides up. She tells us something about Day of the Dead and making paper cutouts, but all I can focus on are the slightly darker-than-cream-colored pit stains burgeoning under her arms as she writes on the board. When she stops speaking and hands out scissors and stacks of paper, nobody does anything except chatter. Ms. Blok can’t do anything about the fact that no one is speaking Spanish in our AP Spanish class.

Ava and I sit at our desk pod, just the two of us. I slowly pick up the scissors and slide my thumb through one of the holes. Ava’s scissors move in and out and around her cardstock. The flurry of swapping paper and grabbing scissors and conversation surrounds us. Out of the corner of my eye I see her eyes flashing quickly to mine and then down. I reach my hand out to pick up my piece of white cardstock, slowly enough to steady my hand.

“Of course you chose white,” Ava says to me, a little too quickly and a little too loudly. She flicks one of the rejected scraps of paper off of her desk and onto mine with her nails that are marbled with pink, blue, and purple polish. She loves marbling her nails. She spends hours dropping droplets of polish into a cup of water, swirling it around, and then dipping her fingers in one by one. The polish is chipping on her ring finger and thumb, but each nail still looks like its own miniature Van Gogh swirl. They look better than my nails could ever look. She flicks another scrap at me. “Yours is going to look like a paper snowflack,” she says. Ava says things like saLL-mon instead of salmon and tort-iLL-a instead of tortilla and snowflack instead of snowflake. Her paper is red. Her favorite color.

“Hey.” She nudges me. In her nudge is the hint of a question. I give the tiniest shake of my head before really looking at her for the first time today. She’s wearing The Shirt. She did that on purpose.

The first time I saw Ava was the third day of high school, when she stood in front of me in the lunch line wearing The Shirt. It was patterned with Starry Night by Van Gogh, but the colors were inverted so that, instead of black and deep blue and yellow, they were white and straw yellow and bright blue.

My brother Mo told me before I started high school that I should speak up more because I tend to be quiet around other people. I told him that my thoughts are so loud I don’t understand how no one else hears them, and that just because people can’t hear them doesn’t mean they aren’t loud. He rolled his eyes and then lunged toward me, tickling me until I whisper-screamed stop so that Mom wouldn’t hear us awake.

“See,” he said, “I couldn’t hear your thoughts telling me to stop.”

I told Ava I liked The Shirt because I did but also because Mo told me to talk more, and she turned around so fast that her frizzy dark ringlets sort of whacked me in the face. She smiled really wide and launched into the story of how she had been looking for a clothing item, any clothing item, with Starry Night in inverted colors for years because, while she liked the painting as is and all, she didn’t like how realistic Van Gogh’s colors were on a canvas that clearly depicted a modern, post-impressionist view of the night sky. We plopped our sloppy joes onto the gray lunch trays and walked to a table, still mid-conversation. She told me she had eventually gone online and found a DIY site where you could upload images onto a shirt yourself. I told her how I loved the white of the inverted color scheme so much more than the traditional black and how black was such a selfish color because it absorbed the light whereas white was entirely honest. And also how Mo always wore white shirts because he had green eyes, too. She paused.

“No one has ever complimented my shirt before.” She looked me up and down, eyes lingering a second too long on the turtleneck I wore even though it was early August. She then stuck her left hand straight out. “I’m Ava. What’s your name?”

“So, I was thinking,” her eyes are on me in a way that makes my skin crave sunscreen, “that if you aren’t up for it you shouldn’t come over after school tod—”

“No, I will.” Ava’s shoulders schlump a little at my tone. I maneuver the scissors the way Mo taught me to when I was little, through and between the paper as I cut a triangular sliver and then arc a half circle around it, wondering how the symmetry will turn out when it unfolds.

“Day of the Dead paper cutouts,” I say, mostly so her shoulders will perk back up, “and geometry?” She lifts her eyes and lets a hesitant half smile rise on her cheeks, so I can just barely see her teeth that are splayed out in the front.

“In the book?” she asks.

“In the book,” I say.

I’ve never understood why subjects in school are delineated. People talk about the sciences versus humanities but in my head every bit of information works together. I asked Mo once why subjects are separated, and he rolled his eyes and told me that was just how it was. I said why and he said because and I didn’t say anything after that.

We were diagramming plot structure in English one day and I was looking at how the diagram starts level and then increases before decreasing and leveling out again at a point higher than where it began. It looked exactly like the graph of an endothermic reaction in chemistry. Which makes perfect sense because after reading a story people have more potential and more energy at the end.

Plot structure also made me think of graphs in calculus, because if you took the derivative of the arc of a story it would give you the trajectory at each point, which feels like an important thing to know about a story. And if you integrated the plot diagram you would get the area under its curve. I’m not sure what that means yet, but I think it’s probably important. When I Googled derivative of plot diagram later nothing came up on the internet. Textbooks should have and could have been written about it if people stopped needing to always separate things. I told Ava this and asked her why there weren’t those textbooks. She looked at me and changed the subject. But the next day in English she pulled a mini composition notebook out of her backpack. She shoved it towards me so that I could read the first page, which said:

1. plot structure, endothermic, derivative

and below that the number 2 with blank line after it for us to fill in.

“We’ll write the textbook,” she said, and slid the notebook back into her bag as our English teacher began talking.

We hung out at her house and never mine, and I told her it was because my parents worked late and didn’t want me home alone. Some days I told her it was because I had art class at night after school. I don’t even go to an after-school art program. It just sounded like something I would do.

When I told Ava about Hayden, I told mostly the truth surrounded by a whole lot of lies. I told her he was in my after-school art class. I told her that my art teacher was terribly mean, even though she probably didn’t intend to be, and that she always took out whatever anger she was holding inside herself on me. I told her that Hayden never stood up for me, never said anything to defend me, even though we’re supposed to be really good friends. I started telling her by accident, but once I started it all slid off my tongue too easily to stop.

Ava had a jade plant on her desk at home, and when I first saw it I told her that the scientific name of jade was Crassula ovata, and that Mo and I would spend hours going through a plant book with scientific names, and that his name wasn’t really Mo that was just his plant name that I called him. And that he called me Vi because the scientific name for hazel, the color of my eyes and also my actual name, is Hamamelis virginiana.

She got really excited and wanted me to give her a plant nickname, but I told her only Mo is allowed to give them. She kept nagging and asking if she could come over and meet him after my parents came home from work and after he came home at night from community college. I kept avoiding answering her but finally said that my mom would be way too tired after work.

“What about your dad, though?” she asked. I told her I meant to say him too before changing the subject because, even though Ava was Ava, I’d never told her that I’d never met my dad.

Mo finally came over with me to Ava’s house last night instead. When he asked her what her favorite plant was, she told him she liked ferns.

“Onoclea sensibilis,” he said immediately. “That’s the scientific name for a sensitive fern. You could use Clea.” I saw her look him up and down, eyes flicking from his white, short-sleeve shirt to my turtleneck that was yellow today. She’d asked me once why I always wore a turtleneck, even when it was hot, and I had told her I liked the way they felt cozy around my neck. She rolled her eyes and said why don’t you just wear a choker then? I said it’s not the same.

“What plant is Mo for, again?” she asked my brother.

“For Marchantia polymorpha,” he told her. “Liverwort. That’s the color green my eyes are. My actual name is Hayden,” he told her. She paused only for a second as she glanced toward me and then back to him.

“I’m Clea,” she stuck her left hand out and said almost in a whisper, “Nice to meet you. Hayden.”

Ms. Blok always wears her auburn hair in a crooked, wispy bun that whispers hints of how put-together it had been in the morning.

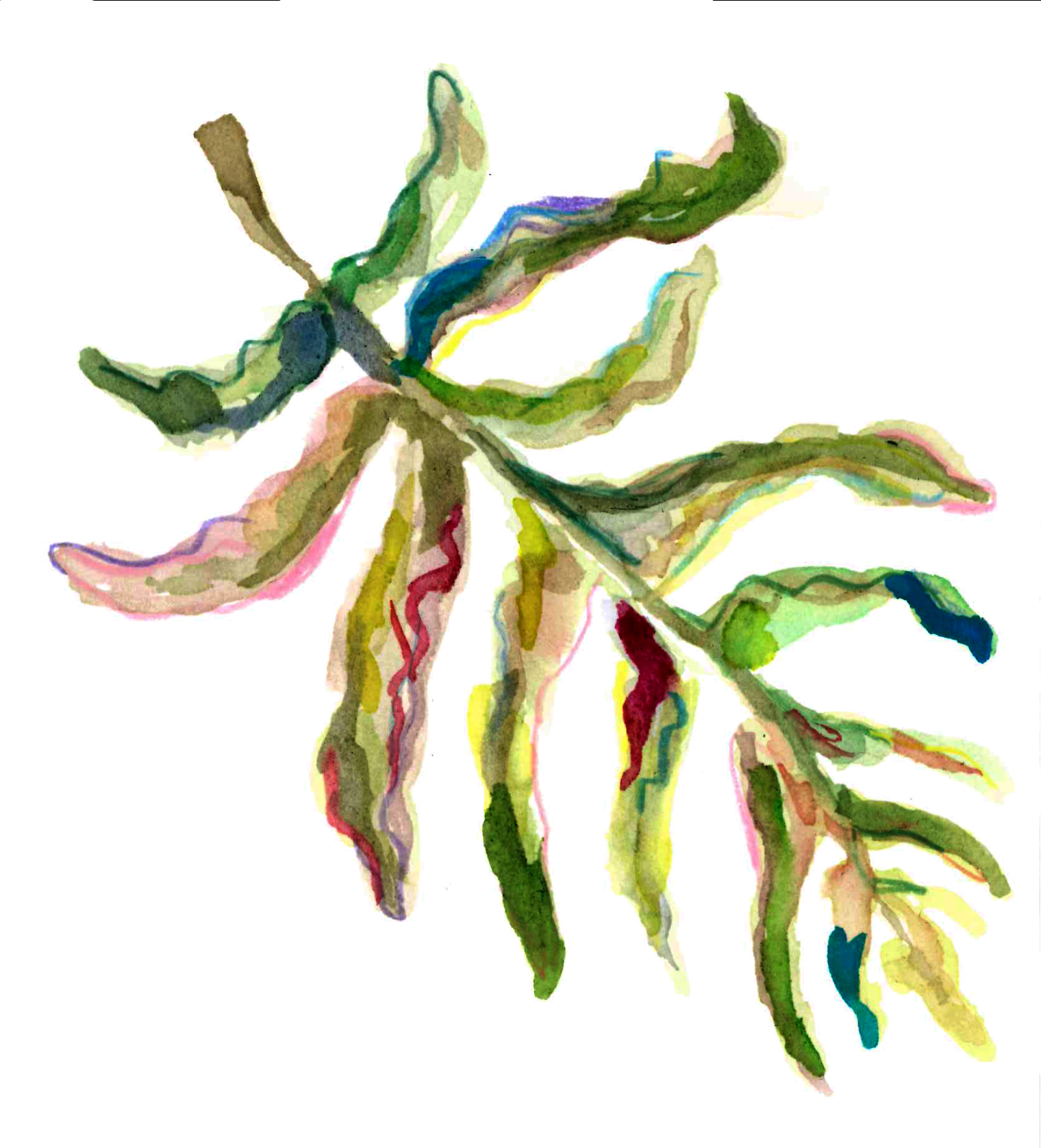

“Have you ever noticed how her bun is always crooked?” I ask Ava while she cuts her paper. I lay my finished but unopened cutout on my desk. The scraps from her red paper mix with the scraps from my white paper and look like the petals of Dahlia pinnata. Dahlia flowers.

“I mean, it wouldn’t be that hard to straighten her bun. Or teach her how to do a good bun,” I continue. She doesn’t not look at me, but she doesn’t look at me either. “Maybe we should offer to help her.”

When Ava reaches out to touch my arm, she accidently brushes back my sleeve just enough to see purple, not unlike the color of Ms. Blok’s bra. I shove the sleeve of my turtleneck quickly down. Her already large eyes widen and lock with mine, and I hear her take a quick intake of air. I pull my arm away, still staring at her. For a second, while her hand lingers like a prompt, I consider telling her the whole truth about everything.

But she breaks eye contact, lets her hand fall, and reaches across to the white paper cutout sitting unopened on my desk, unfolding it slowly before holding it up to show me.

My cutout is really very good.

“It’s a snowflack,” she whispers, and lets it fall, open, onto my desk.