It was Laying Day. Sam shivered in line outside Susan B. Anthony High School and chewed over the rumors: The exacting judges, the rare perfect sheen, the time that guy screamed like a goat. The morning fog hung thick, blurring a neon “WE BUY GOLD” sign in the window of the pawn shop on the corner. Sam stared at a homeless dude sleeping under an awning across the street. What had his egg looked like?

The doors hadn’t opened yet, but the line of teenagers already snaked along the school’s brick wall, down the block and around the corner. Most sat sleepy-eyed on the gum-speckled sidewalk. Caffeine tightened muscles down there so coffee was a no-go on Laying Day.

Sam stood. He picked at the mole on his neck, which had sprouted its second hair last month. He was tall for 15, and his sweatshirt hung loose on his lanky frame. “Better tall than bald,” his dad always said. Sam fumbled in his backpack for his copy of “David Copperfield.” Dickens was a key de-stressor.

The girl in front of Sam in line was whispering into her iPhone. She was wrapped in an orange and black SF GIANTS blanket. “The point is I don’t need — wait. Dad. Didn’t we say talking on the phone was a complete no-go in terms of — OK, you’re stressing me out. Bye.” She pocketed the phone and hit the brick wall with the palm of her hand, face tight as if she’d tasted something sour. Sam laughed.

“What?” she said, turning around.

Her canny eyes made Sam squirm. She reminded him of an anteater. “Oh, um — just something in—” He pointed to his book. Shit. His face was a big-time tomato. He looked down and flipped a page.

“I’m just messing with you,” she said. Her pucker morphed into a smile. “I know I was being—”

“No no no,” Sam said. “You sound like me with my mom. This morning I was like, ‘Mom, you better not call before I lay, even if the house is literally burning down.’” Why had he done that weird voice? Sam leaned against the wall like super-chill.

“My dad has no self-control,” the girl said. She stuck out her hand. “I’m Susie.”

“Sam.” They shook. “Um — so, what school do you go to?” He brushed his hand on his pants to wipe off the sweat from the shake, then covered with a swipe through his hair. His fingers snagged on a knot.

“Brimton,” Susie said, as Sam struggled to extricate his middle finger from the tangles without flipping Susie the bird. Rats. He’d forgotten to listen to her answer.

“Yeah, like no one’s heard of it,” Susie said. “It’s in the Richmond, over on Clement. You?”

“Collegiate,” Sam said. Susie raised her eyebrows.

“Your parents must be super-rich,” Susie said.

“Not really? My dad—” Sam realized Susie didn’t care. He picked at his mole. The coarse hairs felt good on his finger.

“Well,” Susie said, “both our parents paid the big bucks for us to lay in the first place.”

“Seriously,” Sam said. “Kind of wish they’d asked me first.”

“Oh,” Susie said. “I feel like not doing it puts you at a huge disadvantage?”

“Probably,” Sam said. “My dad’s obsessed. He talks about what I’ll tell my grandkids.”

“I heard more people aren’t doing it this year,” Susie said.

“Activists,” Sam said. Eyeroll.

“Hey,” Susie said, “doesn’t Collegiate have a trophy case with the best half-shells in school history?” Sam nodded. “That’s so extra,” Susie said.

“Yeah.” Perfect symmetry. Flawless color. A single curl that’s really blue. Sam’s left eyelid began to twitch.

“You’re such a nerd.” Susie grinned. “Collegiate sounds awful.”

“I’m pretty sure everyone with a half-shell in that trophy case is now, like, a gazillionaire.” The front doors of the high school creaked open and the line started to move. “Whatever,” Sam said.

“Whatever,” Susie said.

An hour later, Sam stood at the end of a long hallway lined with lockers, a few yards from the double doors between him and the school’s gym. Out came Susie with a carrier bag. Tears sparkled in her eyes.

“Shoot,” Sam said. This was not a scenario he’d prepared for, girl-wise. “That bad?” He gave her an awkward hug.

“Thanks,” she whispered. When she pulled away, she was laughing.

“Just messing with you! I teared up when I laid. It fucking hurt.”

“Let’s see it,” Sam said, relieved and newly terrified. He wiped his palms on his jeans again. Susie reached into her carrier bag and pulled out her egg.

Not bad. Nice sheen, an elegant green swish, though a bit of discoloration in two spots. Texture was great — super-smooth — and the shape was pretty darn uniform.

“This looks great!” Sam said. He didn’t ask about her scores. “Looks like, in terms of size, it’s going be a chicken?”

A severe man burst through the double doors, his bushy eyebrows leading the way. He had horn-rimmed glasses and thin lips, and wore all black except for a white collar and a small Easter egg pin on his lapel.

“Next,” said Father Mark. Darn — Sam had hoped for a stranger. He stepped forward, hoping his childhood pastor wouldn’t recognize him.

“Sam! Good to see you.” Father Mark patted his shoulder.

Double darn. Sam hated being patted.

“Good to see you too, Father.”

“See the Sharks game last night?” Father Mark was obsessed with ice hockey.

“Nope.”

Father Mark chuckled. “Johnny Mitchell was on a roll. Three goals. And Stan Kriniewski? Best goalie on the face of the earth.” He paused for a moment, turned, and plunged through the double doors, brows first.

“Good luck!” Susie called, as Sam followed.

The gym smelled vaguely of soy sauce. A mess of piping obscured the high ceiling, and fluorescent light reflected off the polished wood floor. A few banners with school records hung on the walls. Sam’s mom had filed a complaint on account of the gym being unsanitary, what with the sweat and shoe grease. But because of the economy, it was the only space that made sense.

Half the gym was hidden by a curtain. The judges table sat in front of the curtain, near half court. Father Mark walked over and joined another judge. Sam recognized her as the principal of Collegiate’s rival, Tomlinson. She had pronounced wrinkles on her forehead, sagging round cheeks and white hair, cropped short. She wore a grey pantsuit, her lips caked in bright red lipstick. Sam felt nauseous. She, too, wore an Easter egg pin.

“I’m Mrs. Mallone,” she said. “What’s your name?”

“Sam Waldman,” Father Mark said. “He and his parents used to attend St. Cecilia.”

“Charming,” said Mrs. Mallone.

“Well, have at it!” said Father Mark, gesturing toward the curtain.

Sam pulled the curtain aside. It was totally empty in the Laying Area, except for the Cleaner and the Laying Chair, which had been set up right beneath the basketball hoop. It was just like in Prep: an off-white plastic seat with a hole in the middle, footrests on either side, connected to a black tube lined with floppy rubber spikes to prevent crackage. The tube fed into the Cleaner. Sam wiped his cold palms on his sweater and pulled down his jeans and boxers in one fell swoop.

Jeez, couldn’t they turn up the temperature in here? Sam plopped on the seat. He arched his back, planted his feet on the footrests, and squeezed his muscles down there. Big-time eyelid twitching. Why wasn’t anything happening? He took a deep breath. Then a slippery-scratchy sensation right down there and he could feel it moving. It felt a little good. He wondered when — “FUCK!” he yelled. “Holy shit holy shit holy shit.” Now it was a slippery-scratchy burning. Squeeze. Wiggle toes, arch back, press hands in stomach. Squeeze harder. Sam counted in his head: One Mississippi, Two Mississippi, Three Missis — it was over. Sam had laid his egg.

The egg wump wumped along the black tube to the Cleaner like a real-big prey being digested by a python. The Cleaner started to vibrate. Sam jumped up and pulled on his boxers, jeans and shoes. He heard his dad saying, A watched pot never boils. Click. A drawer popped out of the Cleaner. There was his egg.

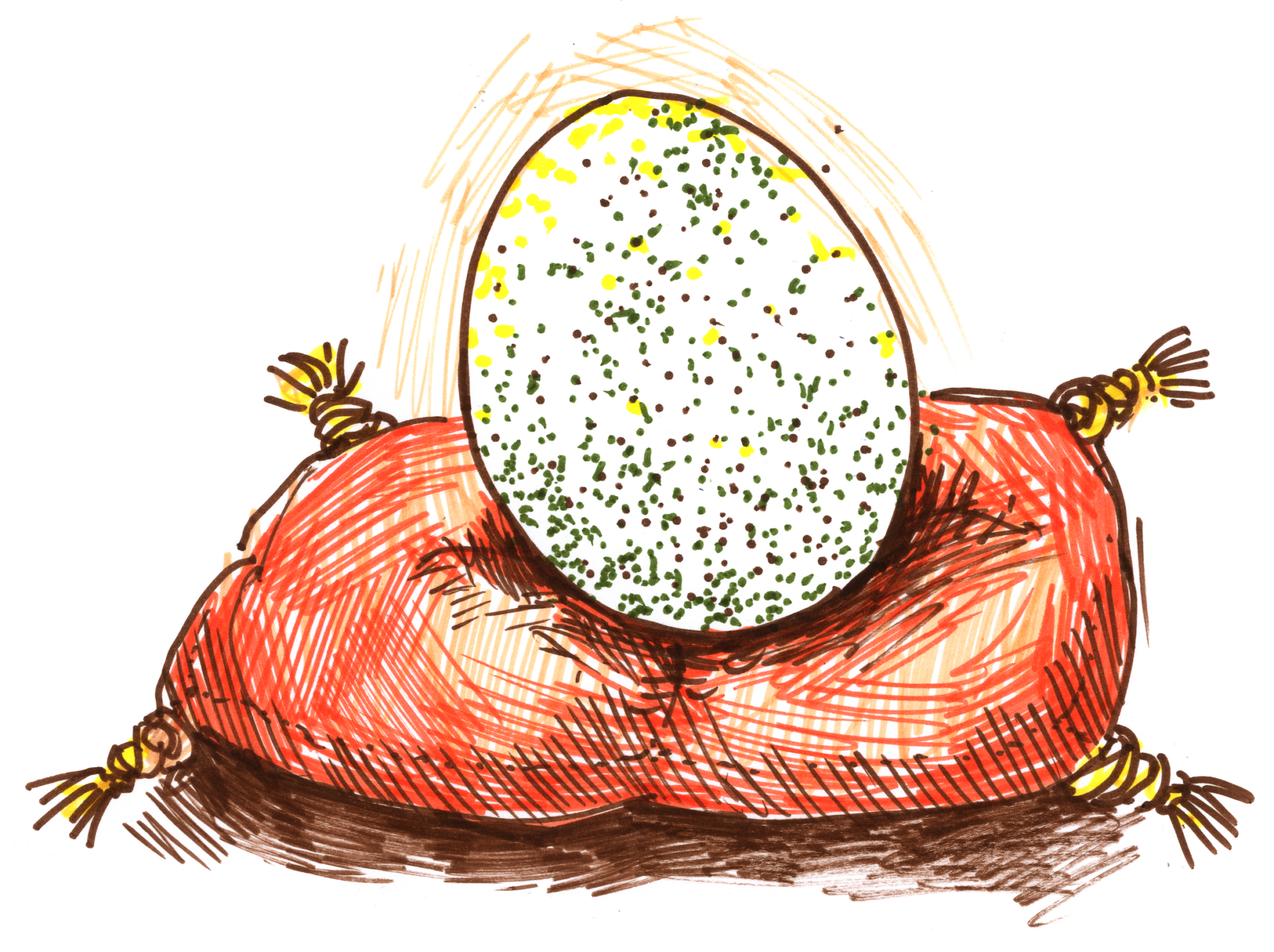

Holy wow! It was a beautiful pale white, with a sultry swoop of red curling around the middle like a bow and a few choice specks of yellow. Very solid sheen. Texture was a little rough, but shape was flawless. Definitely big enough to be a turkey. He cupped the egg in his hands and ducked under the curtain.

“Well done, Sam,” said Mrs. Mallone. “Please place your egg on the inspection cushion.” Sam set his egg on the little velvet cushion with gold tassels that sat in the middle of the table. Father Mark and Mrs. Mallone scribbled some efficient notes in their notebooks; Mrs. Mallone rotated the egg as if she were making sure all sides were cooked evenly. They both nodded. Sam stood and watched.

“OK, I’m ready if you are,” said Father Mark.

“Sure,” said Mrs. Mallone.

“So, Sam — job well done, in my book,” said Father Mark. “I’d say 89th percentile on color definition? Very clean edges on the red swoop.”

“Thank you,” Sam said. He picked at the mole on his neck and smiled. His stomach squirmed. Don’t let your head get too big, he heard his dad saying. You won’t be able to get out the door.

“I’m OK with that,” said Mrs. Mallone. “And 91st for hue? Those yellow dots are really quite something.”

“Let’s say 90th,” said Father Mark. “Sheen?”

“82nd?” said Mrs. Mallone. “And let’s do 71st for texture.”

“I’m OK with sheen, but let’s bump texture,” said Father Mark. “73rd?”

“Fine,” said Mrs. Mallone. “Tell me if you disagree, but I’d say 97th for shape.”

Father Mark thought for a moment, and checked his notes. “How about 98th?”

Mrs. Mallone smiled at Sam. “Works for me. I think that’s everything. And Sam, dear, it looks size-wise like it’ll probably be a turkey. Will your parents be okay with that?”

“This is San Francisco,” said Father Mark.

“Yeah,” said Sam. “My parents are pretty progressive.”

“Lovely,” said Mrs. Mallone. She pulled out a card and wrote down Sam’s percentiles. “We said 82nd for sheen, right?”

“That’s right,” said Father Mark. He placed Sam’s egg in a carrier bag. Mrs. Mallone handed the scorecard to Sam. “Thanks very much, Sam,” said Father Mark. “We’re looking forward to seeing your turkey.”

*

Crack. Sam sat on his “Matrix” bedspread and watched his egg jiggle ever so slightly back and forth in its incubator. It was a month after Laying Day. A miniature seam appeared in the shell just under the red swoop. Sam had convinced his parents to buy him an IncuDeluxe for this very reason. (IncuDeluxe auto-adjusts its temperature to maximize crackage in the egg, making it easy for the chick to hatch. Now only $99 at Target!)

“Mom, Dad, it’s happening!” Sam yelled. He heard feet banging on the wooden stairs up to his room. Sam’s parents burst through his door. His dad sat next to him on the bed. His mom hovered nervously in the corner.

“This is it, son.” Sam’s dad put an arm around him. “I want you to know we’re fine with a turkey.”

“Oh, Sammie, we’re so proud of you,” Sam’s mom said.

Crack. The shell fell away and a tiny, fluffy head poked out. The chick’s feathers were damp and bedraggled. Sam opened the incubator and pulled away the rest of the shell.

“Yep. It’s a turkey,” he said, his stomach tightening.

“That’s great, Sam,” his dad said, whacking him on the back.

“Yes, great, Sam,” his mom said. They craned their heads over his shoulder. Sam picked up the chick and held it in the palm of his hand. The knot in his stomach disappeared. The chick’s neck was so fragile, like a fluffy twig. Sam’s mom snapped pictures on her iPhone from every conceivable angle.

“Let me take a gander,” Sam’s dad said. He took the chick in his hairy hands and it clicked. Sam caught himself imagining the proud day that his chick would cluck.

“This sucker is going to taste great,” his dad said.

Right. Sam’s smile evaporated. He stared at the ribbons his mom had pinned up on his bulletin board.

“We already signed you up for a slot, Sammie,” his mom said brightly, putting a hand on his arm.

“Trust me,” his dad said, “you’ll be telling your grandkids about this.” His ponytail bobbed up and down as he talked. “I remember the moment I sat around the table with my family and ate my chicken. My dad said, ‘I’ll be darned,’ and that was just about the nicest thing he ever said to me.”

Later, Sam called Susie. They had stayed in touch since Laying Day, mostly sending shots of their eggs in their incubators with egg-pun captions. Susie’s chicken had hatched a week earlier. She had kept Sam updated on the whole process.

“Hi, it’s Sam.”

“Hey.”

“Yeah. Um — so, big news. My turkey hatched.” Sam tried to sound enthusiastic. Susie had been so pumped about her chicken.

“Were your parents cool with it and everything?” Susie asked. “You hear those stories where progressive parents actually aren’t so progressive…”

“Nah, they were fine,” Sam said. “I’m thinking about naming him.”

“Literally, why?” Susie said. “They specifically say you shouldn’t do that in Prep. Studies show that one in six get attached, you know?”

“What do you think about Max?” Sam said.

“Sam.”

“Why not?” Sam said. “I like Max.”

“I mean, it’ll probably taste better if it doesn’t have a name,” Susie said.

“Aren’t you at all sad?” Sam said. He lay back on his bed and stared at the paint bubble on his ceiling.

“Why would I be?” Susie said. “It’s just a chicken. No different than the grocery store.”

“Except — you laid it?” Sam said.

“Are you saying you’re better than a mother hen?” Susie said. They both laughed. “Honestly, I’m excited. I feel like if you eat meat, you should be willing to kill it yourself. And it’s such a cool tradition—”

“No way,” Sam cut in. “There’s just no way that I’m going to kill Max.”

*

Four months later, on a Sunday afternoon in late August, Sam once again stood in line outside Susan B. Anthony High School. He was choking back tears. He had gotten in a huge fight with his parents and they had said they wouldn’t pay for his college if he didn’t go through with it. They had no room in the house for Max, and sometimes, they told Sam, you just have to respect your elders.

The weather was foggy — not hot enough for short sleeves, but not cold enough for a real jacket. Sam was next. He held Max close to his body and he could feel Max’s heart beating against his stomach.

A young volunteer emerged and beckoned. He was wearing a neon yellow shirt with a cartoon chicken. Sam recognized him — he was a senior at Collegiate on the football team. He had some serious stubble and big-ish biceps. A lot of the football guys volunteered after church.

“Hey, Patrick, right?” Sam said. “I’m Sam.”

“Yeah, I recognize you,” Patrick said. “You’re the one who laid in the top five at Collegiate. Red swoop, right?” Sam nodded. “Killer egg, dude.” His voice sounded like a gurgling drainpipe.

“Thanks,” Sam said. He forced a smile.

Sam followed Patrick into the school. They walked for a minute and then Patrick pulled open a classroom door decorated with a big poster of Toni Morrison. “Here’s your station,” he said. A gawky red-haired guy stood inside, wearing a big white smock and yellow rubber gloves. The first thing Sam noticed were the dots of blood speckling the smock, like the guy had just stepped off the set of a horror movie.

“You’ll work with Danny,” Patrick said to Sam. “Danny’s a senior at Lakemore.” Sam nodded at Danny but said nothing. Patrick disappeared and Danny shut the door.

He stared at Sam. His eyes were soft blue. “You okay, Sam?” he asked. Sam noticed that he had a speech impediment.

“Not really,” Sam said. His throat felt prickly.

“Activists?” Danny pulled off his smock.

“Nope. I just don’t want to kill Max.”

“Ah,” Danny said. “Named him. Big mistake.” Sam smiled as tears formed in his eyes. “If you were going to do the whole naming thing you should have named him something dumb, like Gobbler, or gone all Presidential Turkey Pardon and named him Freedom.” Sam laughed. He scanned the room. A plastic sheet covered the gray carpet. A few knives lay on the teacher’s desk. A pot of water bubbled on an electric cooker in the corner. In the center of the room stood a tetherball pole with an upside-down metal cone attached to its side, and beneath the cone sat a white plastic bucket.

Danny came over and patted Sam on the back. “It’s gonna be okay, dude.”

“Thanks,” Sam said. He still held Max tightly in his arms.

“You know, it’s speedy,” Danny said. “And it’s not like he’d live for years anyway.” Sam nodded. “He’d have a miserable life in your room.”

True. Sam’s room was very cramped. And it was a drag to take Max down to the backyard four or five times a day so he could peck around the grass. What would happen when he started school in a few weeks? Plus, Danny seemed like a good guy. They would never have met were it not for this day.

“He won’t even know it’s happening,” Danny said.

Sam gave Max one last squeeze. “Okay.”

Danny pulled back on his smock. “Alright, the first step is to put him in the cone. I’m sure Max would want you to help.” He handed Sam a white smock and a pair of yellow gloves.

Sam lifted Max and stuffed him headfirst into the cone so that his head poked out through the small end at the bottom. “Am I doing this right?” he asked.

“Yeah, perfect,” Danny said. Sam smiled.

Danny grabbed one of the knives from the table. Sam stared. For a moment, he felt like he was going to puke, right there on his shoes, but he got it together. He remembered what he and his dad had discussed in terms of this day not being easy, but good character-wise.

Danny grabbed Max’s head with one hand and sliced into his neck. Blood poured into the bucket. It sounded like the rain on Sam’s bedroom window during a storm. Like a mini waterfall. Danny kept his hand around Max’s head. They listened as the waterfall subsided into a plop-plop-plop, and then nothing. Max was still.

“You did way better than most people, dude,” Danny said. “No one’s vomited yet at my station, but I’ve heard stories from the other guys.” Sam forced a laugh.

Danny dunked limp-Max in the boiling water in the metal pot. “To loosen the feathers,” Danny explained. He handed Max to Sam, and let Sam dunk the body a few more times. Sam felt like a real man. Now, when he ate meat, he’d know exactly how it was killed.

Danny grabbed Max’s feet and pulled him out of the water. He dried the body with some paper towel, and threw it on the table. Danny showed Sam how to strip the feathers; how to remove the oil gland and feet; and how to cut open the body to get the entrails. They talked about Sam’s super-dumb English teacher (Mr. Randolph) and about Danny’s college plans (San Francisco State).

Danny put the butterball in a carrier bag. “Hey, it was great to work with you,” he told Sam. “Seriously, dude. You’re going places.”

Sam felt springy as he walked out of Susan B. Anthony High School. Sure, it was nice to wake up and hear Max clucking, but think about all the new character points he had just earned. He felt sorry for the kids whose parents wouldn’t let them lay. He couldn’t wait to show the bird to his mom, to cook it with his dad. To provide something, no matter how small, for his family.