Katherine Du

On Wednesday evening, the Yale Center for British Art hosted a panel discussion called “Revealing the Invisible.” The event explored the prevalence of this theme in science, medicine, art and society from the 18th century to the present day.

The event drew from physician William Hunter’s work in the 18th century, in which he stressed firsthand observation and accurate portrayal of anatomical structures and revolutionized medical education and the study of human anatomy.

“Both [talks] were very skilled and erudite. They did a lovely job of answering questions,” said Naomi Rogers, a history of medicine professor.

The center’s organizing curator of the William Hunter exhibit Nathan Flis introduced the event’s two guest speakers: Margaret Carlyle, a postdoctoral fellow at the Stevanovich Institute on the Formation of Knowledge at the University of Chicago, and John Harley Warner, chair of the Yale School of Medicine’s Section of the History of Medicine.

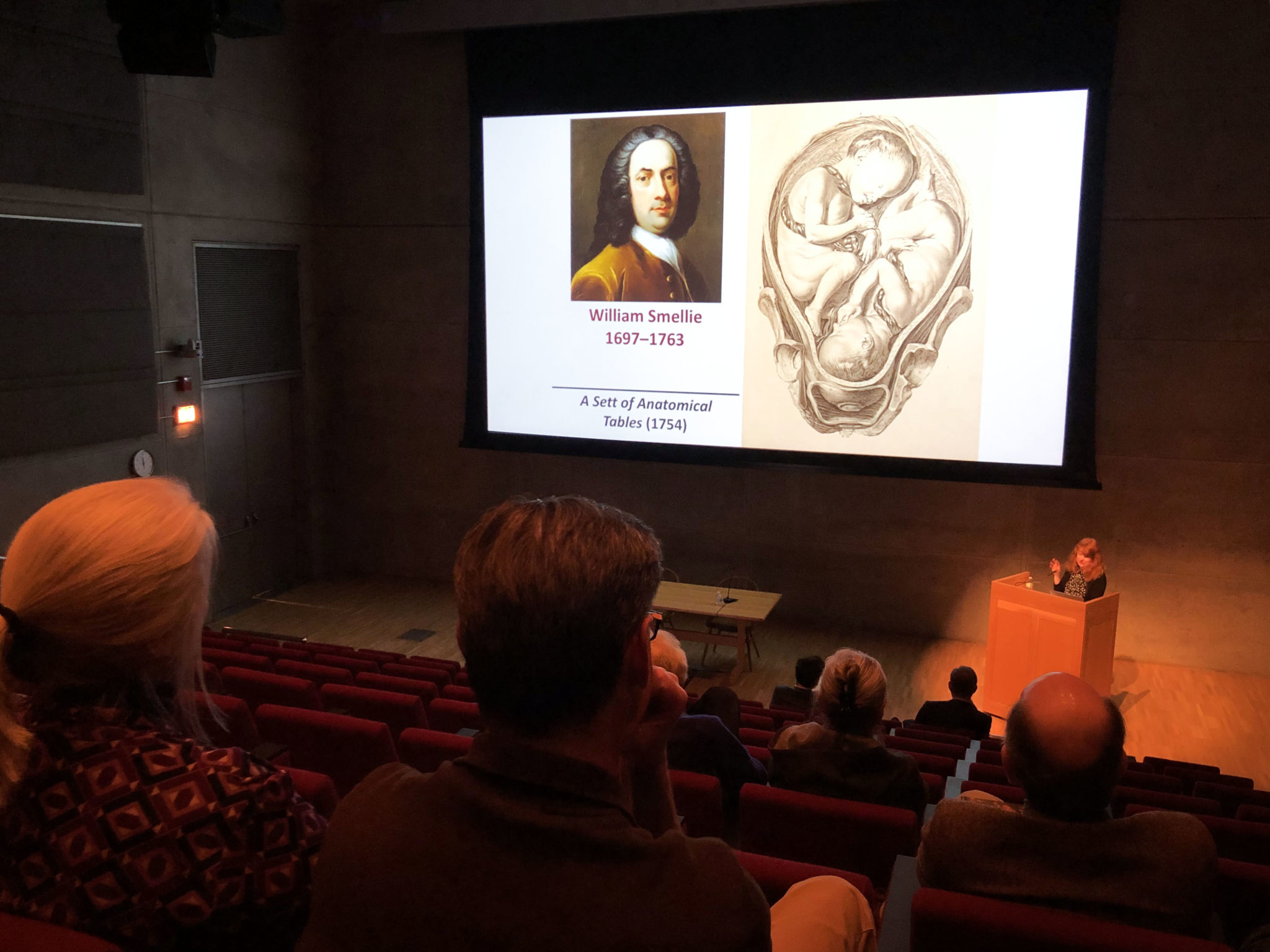

Carlyle’s presentation, titled “Women of Secrets,” focused on exposing and exploring the contributions of women in investigating the human body in Enlightenment France. At the beginning of the presentations, she showcased a watercolor painting of William Hunter’s anatomy school, illustrated by Thomas Rowlandson, that conveyed the school’s integrated approach to carrying out autopsies.

Carlyle pointed out that posters on the walls of Hunter’s anatomy school listed the prices of cadavers and rules to be followed during dissection. She concluded that even in dissecting cadavers, it was proper procedure to observe gentlemanly etiquette.

Hunter’s dissection of pregnant women allowed him to contribute many anatomical representations, including a drawing of the uterus, which Carlyle displayed.

Carlyle then drew attention to Marie-Marguerite Bihéron, a French female anatomist. In particular, she discussed Bihéron’s contributions to the mapping out of the anatomy of the female reproductive system.

Bihéron created lifelike and proportionate wax models of pregnant women, which she showed in a museumlike setting to guests who visited her home. Her models were so realistic that a visitor to her collection, British physician John Pringle, commented on her models, saying, “Madam, nothing is wanting except the stench.”

Despite her scientific contributions, Bihéron was invisible to many, modest and self-effacing, Carlyle said. In her private life, Bihéron also had an intimate relationship with a woman, Madeleine Françoise Basseporte, with whom she worked and resided.

Next, Warner’s talk surrounded the phenomenon of taking group photographs in American anatomy laboratories during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Warner’s slideshow featured variations of photographs with medical students in the dissecting room posing alongside their cadavers. American medical students chose to be photographed both together in groups and at work with cadavers.

Warner found it reflective that the image students chose to take photos alongside gross anatomy and cadavers, rather than with more sophisticated scientific markers such as microscopes.

The racial and gender makeup of the groups was primarily white males. For male students, the group image conveyed a sense of manhood, and for women, the images demonstrated that they could perform the same roles as men, Warner concluded. Commonly, the dissectors were European-American, and the dissected were African-American.

Posing with these corpses shows social, racial and political ideals during the time, according to Warner. He also encouraged audience members to think about what is not shown in the image, particularly the stories of those who worked behind the scenes on cadaver projects.

Barbara Di Gennaro GRD ’20, a history of science and medicine graduate student, collaborated to set up the exhibition.

“The talks were very much in conversation with each other,” Di Gennaro said. “What I found interesting was that it appears that this necessity of dealing with cadavers needs some kind of justification: some kind of justification in the 18th century, a different kind of justification in the 19th century and it still needs some kind of justification today. This [activity] changes in time, but there is always this need [for justification].”

The panel discussion was free and open to the general public.

Katherine Du | katherine.du@yale.edu