Kelly Zhou

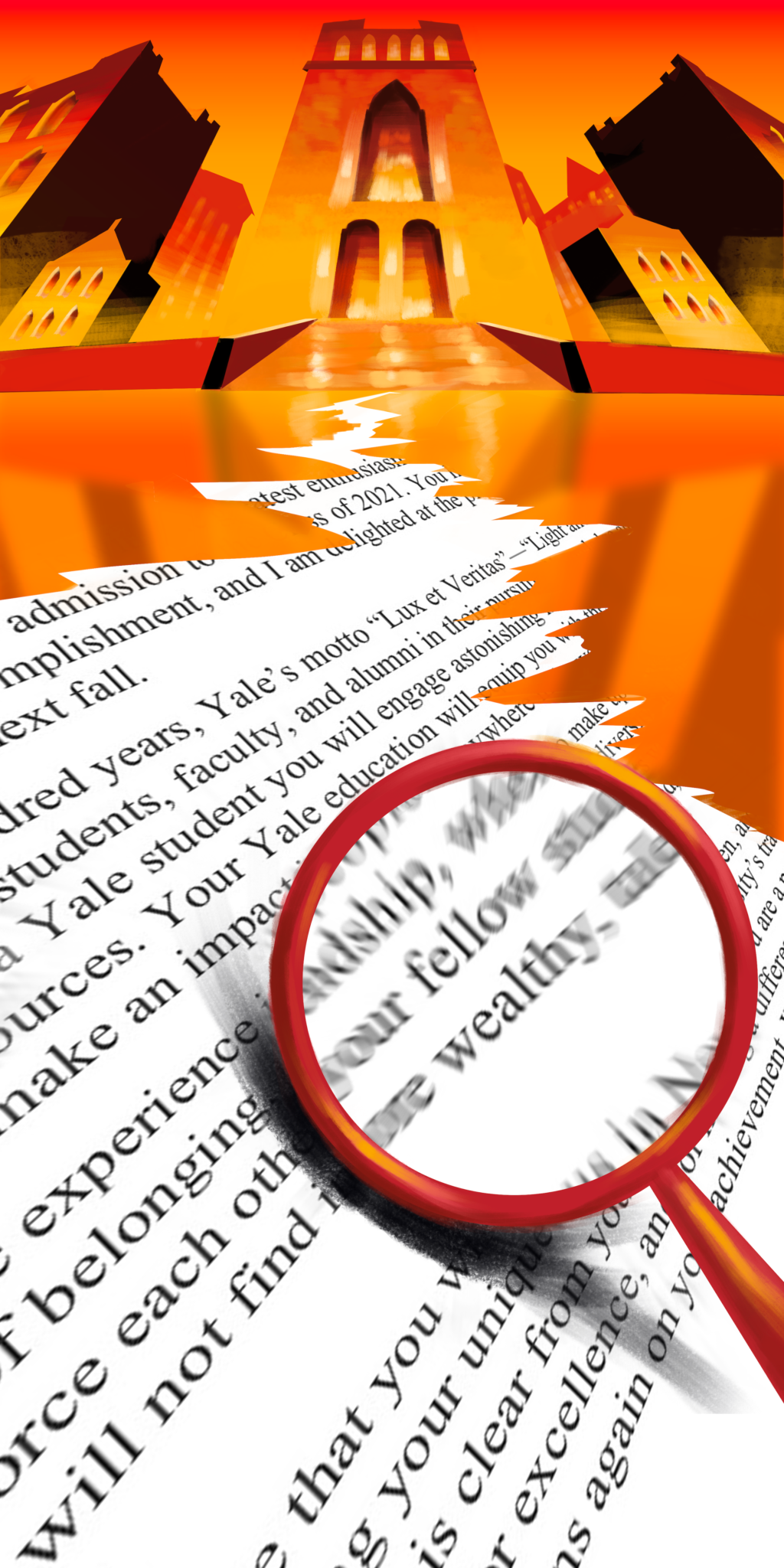

Admissions decisions came out this week. And so begins the national season of reflection: What did I do to get into college? Where did I fall short? And why? We pat those on the back who were granted access and reassure those who weren’t that their excellence was overlooked by those who don’t know what they’re looking for. But we also ask, what are they looking for? And how do we know? Are they using criteria we can accept, or are they missing essential components?

These are questions, though, that we often feel unjustified asking. We made it here, to college, and for that reason, we are among the victors, not the victims, of the system. We find it awkward and uncomfortable to speak about a process that favored us. We don’t feel that it’s our place. But many of us are the victims of other systems at play in admissions. And many are victors of those systems that victimize our peers.

We want the answers. So we interviewed 12 students and professors to artificially curate their candid opinions into a discourse about the admissions process, with its merits and its shortcomings. Each excerpt below is a portion of a longer individual interview strung together for clarity. These interviews have been compiled into a conversation, organized as a transcript from a round table discussion.

There is agreement and rage, satisfaction and resentment, all relayed in a way that could only have been achieved through this form given the sensitivity of the subject matter.

As such, this article is something that is otherwise impossible, typically barred by campus courtesy and fear of backlash. All speakers are granted anonymity in order to assure their most honest speaking about the subject, and each has been assigned a letter A through L to clarify continuous threads of thought throughout the entire conversation.

We asked them all the same question: Is the college admissions process fair?

Fairness & Meritocracy

A. Yale does a good job in choosing the things it values in students who meet their criteria. Yale values creative thinkers — people who contribute but can still handle the work.

B. [But] the current Yale process very much favors wealthy, privileged students. Here’s a primary example: Do people genuinely believe that a small group of elite private high schools are really producing the best possible candidates? Is Andover producing the best students in America? There’s no question that certain high schools are valued over others.

C. The admissions process pretends that it’s getting the best out of a large pool, but it’s more likely just getting the most prepared [students].

B. And rural and inner-city high schools don’t have the same support systems to achieve this level of preparedness. There’s a whole system of informal academic recruitment and information distribution at certain schools and not at others.

D. In this way, “fair” is a strange word. College is only accessible to the people who are in a place where they can pay to apply [to] and attend college.

E. It’s inevitably going to be focused on opportunities [students] have in high school and in life. The whole process is built upon structural inequalities.

F. Because our broader educational system is so segregated by race and class, all colleges and universities have to consider whether their admissions practices and policies will reinforce those inequalities, or try in some way to work against them. … Highly selective institutions like Yale are reinforcing and worsening those inequalities. … They become another site at which the powerful strengthen their influence and status.

G. But people just like to complain about the system.

D. The fundamental question is: Is the system meant to put everyone on an equal playing field? If so, then it’s not fair.

C. I think that one conversation that has come up recently is the difference between equality and equity. Equality is everyone having access to a set of opportunities. Equity is people having equal footing when they arrive at those opportunities.

E. Right now, this equity doesn’t exist: Some students must overcome some things that other students take for granted. Yes, I overcame things to get here but the fact that I was even prepared to go to college is not the reality for lots of low-income students. What it takes to get here by some, on top of what it takes to get here for everyone, needs not be overlooked. In that sense, it’s harder for me than [for] someone whose dad went here, but it’s way easier for me than people who don’t even think about going to college.

H. But Yale tries to equate everyone and evaluate everything within context.

E. I think [your] claim is the one admissions officers use when they try to hide behind grades and scores because they’re “objective” rather than trying to account for why the disparities exist. Meritocracy shouldn’t be what we’re striving for because merit is just based on what you’ve had access to.

I. It’s impossible to define merit in a way that doesn’t take privilege into account. Merit only takes into account the end result, like a score or an essay. But rich people can send their kids to writing summer camps with critically acclaimed writers, or pay for thousand-dollar test prep classes. My point is that even stuff that seems objective is influenced by personal history.

E. People are a product of their upbringing. Meritocracies just look for objective measures, which aren’t possibly considering the range of opportunities.

I. I think the admissions office should consider incline rather than where someone finishes. How steep is the peak they had to climb?

C. Admissions should equally balance a student’s potential to contribute to the school and the school’s potential to contribute to the flourishing of the student. Judging a 17 or 18 year old on their aptitude would overly prioritize how they are going to add to the institution. A pure meritocracy makes people view themselves as a collection of accolades as opposed to individuals who are going to make up a community.

H. There are a lot of Fortune 500 CEOs that are usually more entrepreneurial and risk-averse and creative minded. They are the people that don’t make it into the traditional sense of meritocracy. They don’t necessarily have the best scores.

A. I don’t even think that a 100 percent meritocratic admissions process would be advantageous. What makes Yale so special is being able to interact with people of all backgrounds. A meritocratic system would skew in favor of a specific category of student.

H. If it were a pure meritocracy, shouldn’t this place be half Asian?

I. But we have to be careful: When we conflate race with diversity, we begin to pigeonhole people. We need a more expansive notion of what diversity is if want to have a functional process that accomplishes its goals. I don’t think it’s a meritocracy.

B. Ideally, the system would be as meritocratic as possible while preserving diversity. I don’t think we can have a pure meritocracy if we don’t have an agreed-upon definition of merit.

J. And it’s impossible for the Admissions Office to figure out some eternal ideal of merit.

Legacy

A. I believe that Yale considers legacy in admission because Yale wants people to think they value legacy so that they are inclined to donate. At the same time, however, they cannot emphasize legacy too much, as to discourage non-legacy students from applying.

I. But why even delineate? If you are legacy, having parents who went to Yale is already enough of an advantage in the educational experience growing up. It’s affirmative action for people who just don’t need it.

G. I think it’s good for Yale to maintain relationships with alumni. It’s important to show alumni that you care about them.

E. However important they may be, these relationships, and the money that underpins them, are not essential for Yale to stay relevant, but rather to keep power in the hands of the people who have had it in the past.

H. At some point, though, there’s too many smart kids who are applying to Yale and all these schools. You could have two kids equivalent in all the meritocratic factors, but one kid is a legacy. [Yale] will just take the legacy kid. He doesn’t deserve it less than the other guy. I think that’s sort of how affirmative action works here, too. I think that’s how things should work. Look, other schools are also gateways to social mobility. So, to that kid that doesn’t get in [to Yale] because they don’t have legacy, I would just say: “Sorry, you applied to a school that favors legacy. You can apply to a public school that doesn’t.” That sucks, but that’s how it is for Yale.

Donations

B. The thing is, though, that it’s not so much about being a legacy, but about the wealth that is usually attached to it.

H. The school [has] interests. The school needs money. And rich donors, as much as they want to see ideas come, they aren’t going to donate if perhaps admissions doesn’t have some way to favor them. It’s this quid pro quo, in a way. That’s a cost that the University has to take, in order also to pay for reduced tuition for students.

B. Can we abolish donations and still fund as many lower income students?

E. Yale has an absurdly large endowment. I don’t think they’re hard pressed with money.

H. But the endowment would shrink, and theoretically, the kids who pay tuition wouldn’t be able to attend otherwise.

G. Even though Yale is rich, it relies extensively on alumni giving. Donors are necessary. Honestly, if we admit a couple more students each year because their parents will give millions, as long as they don’t have IQs of 5, I’m completely fine with that.

D. And with the exception of a very few, most students will do just fine here. If I can enjoy a really nice library because a rich student got in, I’m fine with admissions incentives for donors, as long as the benefits trickle down when Yale admits wealthier students.

L. This gets to the question of what to do when you have one rich donor versus one low-income person, with latter being a better applicant. Who should be let in? Obviously, the low-income student deserves it more, but it’s hard to justify denying the rich student when they might be funding the education of 10 other low-income students.

I. [You] can perform calculus to rationalize the acceptance of donors’ kids, but we also must acknowledge that it’s not an objective criteria for admissions.

B. Overall, if we are working to make the system more meritocratic and fair, we should probably abolish the preferential treatment for donors’ kids.

Athletics

J. There should be a quiz show where they put up low SATs and low grades [of admitted students] and then the question you have to answer is like “varsity athlete or child of a billionaire?” There are wildly different standards for different categories of people. And it’s something with which most Yalies seem to be pretty comfortable.

I. I don’t think it’s wrong to hold different applicants to different standards. You have to measure different people in different ways to take into account privilege and disparities in backgrounds of all kinds. The problem is that the Admissions Office is holding rich kids and athletes to lower standards, even though they often don’t need institutional preference to succeed as applicants or students. Different standards with regard to different applicants are fine so long as these standards are calibrated to account for and decrease inequity.

L. The requirements for football players are less rigorous than other teams, perhaps. But, athletes host parties. They add a lot of diversity.

G. Athletes also make campus more fun, which is very important. This is an academic institution, but it’s also a place we come to have fun and we can be irresponsible. Athletes help create that sort of environment.

A. And athletes work insanely hard here.

K. They are also very committed and intellectually curious. If they were randomly distributed, I wouldn’t recognize them as being student-athletes based on their performance. My class would not be what it is without them.

B. [But] I think part of it is just American sports culture, which places athletes on a pedestal. That’s why we idolize professional athletes.

J. And the weird part is, we don’t even care about sports as a community, but somehow we still insist on valuing Division I athletics as much … as places like Michigan and Notre Dame.

E. I find it funny, [though,] when someone who got in for debate criticizes athletes for the way they got in. Why is one thing okay, but another frowned upon?

B. I’m not opposed to athletes getting special consideration for the skills and dedication that they put in. But we must be honest that that is not same consideration given to debaters or musicians in the admissions process. Athletes can write anything on their [college] essays.

I. And when your place at Yale is contingent on your status as an athlete, your place of learning shifts from the classroom to the athletic field.

L. There is a place for athletes here. Without athletes, it would be a completely different campus atmosphere. They add diversity to the community.

I. Is this diversity even necessary? There’s nothing inherently diverse about being an athlete, outside the fact that they play the sport. What is diverse about them that you wouldn’t find in someone that plays a recreational sport?

J. We must be utterly candid about why we are using economic and racial diversity in sports. Do we not believe that there is academic and intellectual excellence in these lower socioeconomic classes? That would be insulting and racist.

B. Saying that athletics is a vehicle for low-income students to make it to the Ivy League is an argument tinged with racial bias: It suggests that Latino and black students could never get in without athletic recruitment.

Potential Improvement

J. The truth is, we are less concerned with who gets in than we are with how we shape them once they’re here — I want people who want to come here to passionately pursue ideas. Some will have great SATs, some won’t, but the way to select for them isn’t who’s good at softball or oboe. If I were creating an admissions process, I would less heavily weigh extracurricular skills, geography and parents’ income in favor of praising a love of ideas and learning. It would be a much more holistic process. It would rely on deeper interviews and more essays and more serious consideration about who really wants to be here. A real holistic process looks for teacher recommendations, it interviews people in a meaningful way that doesn’t favor obnoxious blowhards or just extroverts and it gives people multiple ways to show that they’re serious about ideas. There are oboe players and dancers and football players among the serious learners, they’re just not as good at [those things].

C. [To this end,] the Common Application is good. It asks students to talk about their own experiences and the worlds that have shaped them. It says that things that students generate themselves should be more important than what their parents can contribute financially.

B. But, these applications are disproportionately coming from these high-level prep schools.

C. There seems to be no ceiling for the way people advertise themselves to colleges.

B. Yale claims to be holistic; it claims to be asking, “Did they make the best use of the resources they had available to them?” But their decisions aren’t entirely reflective of this question. Yale needs a better evaluation system.

D. There will always be a holistic admissions process, which will always contribute to a lack of transparency in how Yale admits students, because it’s hard to explain why one person got in when another didn’t.

F. There is no such thing as a strictly “neutral” process of admissions — they will always carry certain biases, preferences and rewards … All universities struggle with this challenge. Rather than simply declaring a university’s practices to be neutral or bias-free, it’s more productive and honest to acknowledge these built in biases and think about how we want to address them.

I. It’s an imperfect system because humans are working with it. I’m sympathetic to admissions officers because they have to read so many applications, so they need a shorthand system for weeding out who they want and who they don’t. I understand, though I think they should reform the preference given to students from certains kinds of high schools as well as the coasts.

B. I think there should be improved outreach and resources to inner-city and rural schools.

H. I just think that the idea that we can all dictate what is morally right for Yale doesn’t make sense, since Yale has its own mission.

J. Yale strives to be a school of serious learners. It’s bad, then, that we put academic excellence lower on the totem pole than other activities once students get here. We are a school that admits people and says that once we do, they don’t need to take classes as seriously. We don’t, in any meaningful sense, insist that you take advantage of the teaching. It’s a very conflicted message about purpose. We never take any departments or majors away. We add and add stuff because donors and students think they want them. It’s consumer-driven. It takes a lot of backbone to say we are going to do one thing and do it well. So, we’re just a smorgasbord at this point, which is fun, but it’s not serving students as well as we might. Serving students well, though, would involve fights and protests, not thank you’s. At this point, we are being driven by a market place logic. And I don’t think the administration has any particular stake in putting the breaks on. If what you want is to go to school with a lot of different kinds of people with different kinds of skills, if you just want to bounce off of a maximally diverse community of people, we’re pretty close to what you want. But that isn’t the same thing as helping you to become better readers, writers, and thinkers. Yale says that they do that, but to do so Yale should be selecting for it in the admissions process.

Shayna Elliot | shayna.elliot@yale.edu

Lorenzo Arvanitis | lorenzo.arvanitis@yale.edu .