Valerie Pavilonis

Engineering centers are not readily amenable to being romanticized. I am writing this in the Center for Engineering Innovation & Design in a sweaty, sleep-deprived, caffeine-fueled fury while sitting in Dean Wilczynski’s office, which he graciously leaves open for students to use at night. My friend is absentmindedly gazing into the workspace below us where a senior hustles to complete his mechanical engineering project, a theatre kid sews costumes, and computer science geeks check for edge cases before the sadistic Friday midnight deadline. Three years ago, I couldn’t have imagined spending my bright college nights this way.

When you skim brochures or read memoirs, especially from institutions with a veritable three century history like Yale, you don’t find mention of modernist science buildings. Instead, you read of old libraries harboring shelves lined with leather-bound tomes and older buildings punctuated by grassy quadrangles. My “Welcome to Yale” admissions packet bore images of Sterling Memorial Library and Harkness Tower, designed in Gothic imitations and forced a medieval aura the acid dropped on them by our institution’s completely sane progenitors. There is no mention of the historic Rudolph Hall, one of the first brutalist buildings in America, or of Ingalls Rink and the Center for British Art, structures designed by the legendary Louis Kahn himself. After all, these places aren’t Yale. This institution is supposed to reek of old money and musty heritage.

I agree. When I first walked through Sterling’s knave, I was enamored. This was Yale — stained glass, heavy leather chairs, worn wooden tables marked with the history of many a paper hammered out at the last minute, well-groomed patrons, staircases with stone steps depressed like clay and seven stories of dusty stacks. It symbolized my conception of a world-class education. I could see myself lounging in one of these chaises, my feet propped on the low marble table, reading my hardbound copy of “The Republic” while waiting for the meeting of my elite secret society. This is what I had moved across the world for.

And yet, two months into my prestigious education, I found myself at the Center for Engineering and Design (abbreviated CEID, lovingly pronounced “seed”). Here, I was greeted by fluorescent lighting, concrete floors, plastic chairs, inhabitants wearing freebie t-shirts from 2012 and a hot water station. One week later I was one of several ambitious suitors vying for “exclusive” swipe access in an hour-long training whose explicit purpose was to make sure you know not to slash your hand off without wearing safety goggles. However, as I soon learned, the CEID does not spurn anyone — 25% of its undergraduate members are in the humanities and social sciences. My NetID and UPI were taken without ceremony, and I was granted access in a magical sleight of hand. My life changed soon after.

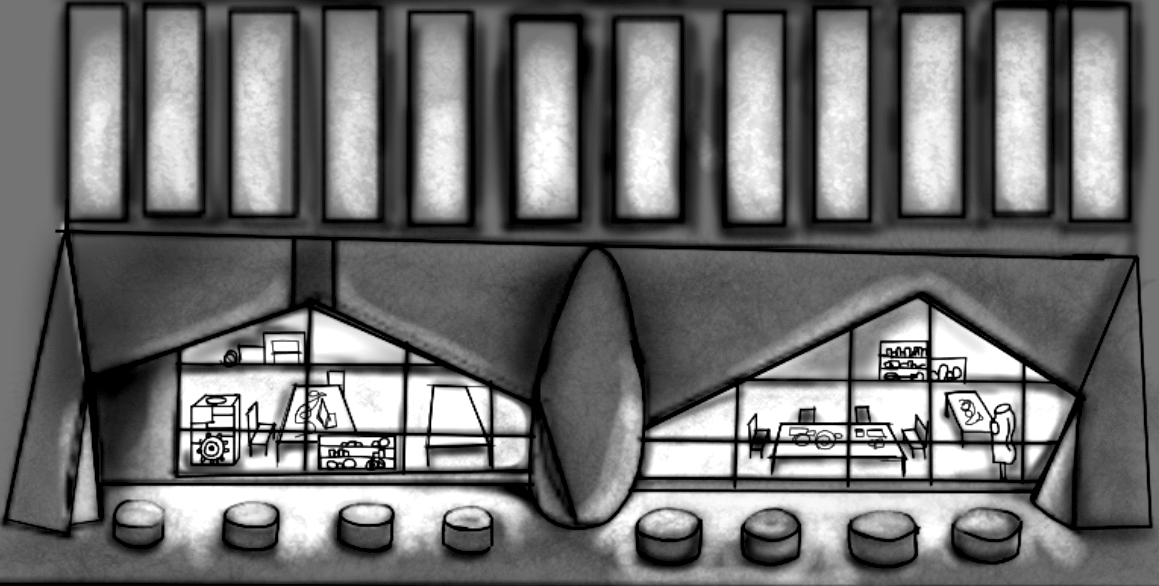

The CEID is ensconced in the forbidding Becton Center, which itself is not devoid of Yale™ pretension. If you look closely, the facade is covered with hundreds of Tau crosses — the symbol of benefactor Henry P. Becton’s secret society, St. Anthony Hall, which inhabits a Neo-Renaissance building just down the block. When you walk into the CEID, you are greeted by a sharp citric smell of wiped surfaces and a blue LCD displaying the names of the multitude of design groups that make the Center home. (Pro tip: never go to the CEID on Sunday afternoons, when the entire Yale Undergraduate Aerospace Association descends over the space.) To the left is the hysterically functional presentation area, with movable furniture and whiteboards on two walls. On the right stands the hot water station and further beyond, lies an expanse of workstations, meticulously arranged wrenches, stationery in every form imaginable, an orchestra of humming 3D printers, and more tools that I don’t use because I would lose a limb if I did. Every afternoon, admissions tour groups stop in the foyer, outside the all-glass front wall, to gawk into the aquarium thus created. They are told that the Center was established in 2012 to support Yale’s unique ‘Y-shaped’ engineers who would apply “intellectual depth and breadth to innovate engineered soluti..*yawn*” as they admire the students, now rendered spectacles, who are undoubtedly thinking up the next Nobel Prize winning idea with the lethal pieces of Legos that litter the floor in indistinct shapes. Upstairs are a row of rooms where you are welcome to sit with strangers. After all, you can’t be separated by more than two degrees thanks to the incestousness of friend networks that have the CEID as a focal point.

The space sees many visitors during the day: students attending design classes, whiling away the time before a meeting or passing by career sessions held by firms to recruit engineers from a liberal arts background to manage the client-side. After sun down though, the space exudes a different aura. Many are lured in by 24-hour access — the promise of never being kicked out by the draconian laws that prevail over other libraries, only to eventually find that they wish somebody would force them to leave. Others, like me, are enticed by the unlimited supplies of hot water and tea, (almost) always in stock and replenished with an efficiency that would put Queen Elizabeth’s footmen to shame. However, the CEID assumes its purest form on weekend nights when only the most faithful remain — foregoing alcohol-soaked parties for anxiety-drenched misery of numbers, code, the occasional essay and eternal companionship. Many spots on campus — the CTL, DHL, HLH17 — have jumped onto the neoliberal bandwagon of encouraging “collaborative” spaces plastered with signs admonishing you to talk in your “outside voice.” The CEID, with its detritus of pencil shavings, sharp edges and MakerBot polymer, encourages this camaraderie organically.

There is something to be said about how the spaces we inhabit on campus are a function of our personalities, but also shape who we become over our four years here. Yale makes bold claims about the microcosmality of the residential college system, which are uncharacteristically true. In Pauli Murray, I live with a maps-obsessed environmental studies major, a political science major who plastered our wall with pictures of Dante, an a capella aficionado with nine varsity letters, and a Brooklynite turned Connecticutian who can do the best British-accent in a two-mile radius. But there are also other spaces that we occupy of our own volition, instead of being compelled to do so by binding randomized lotteries. Our inhabitance of these places has an aspirational quality to it. We may tell ourselves we are optimizing for location — Bass from Berkeley, Haas from Pierson — but we are subliminally acting on our ambitions of our best selves. We hope the spaces we pick will somehow improve us, making us more creative, analytical, cool or edgy. They often do. When I came to Yale, I thought I’d study Ethics, Politics and Economics. I ended becoming an Economics and Statistics and Data Science major — at the cusp of STEM but not really in it. Instead of debating grand strategy in Rosenkranz’s seminar rooms, I have spent my afternoons solving problem sets in the CEID. Spending time here has made me closer to the STEM community. Three years ago, I couldn’t have imagined that I would one day understand references in Mathematical Mathematics Memes and Wild Green Memes for Ecological Fiends or be riled up by Reddit’s UI change. And yet here I stand as a jaded junior, having wasted innumerable hours in the CEID watching Planet Earth and debating obscure Twitter references.

If residential colleges are microcosms of Yale, the departmental hives undergraduates sequester themselves in provide a more “specialized” sense of community. The humanities occupy the oldest buildings from the original Old Brick Row, progressing to the social sciences on Hillhouse Avenue and crescendoing with the menacing Kline Biology Tower and its web of science buildings. During our daytime academic lives, after the dust from declaring a major and finding a path has settled, we could forego incidental interactions with those in other fields entirely. Our study spaces thus become our physical echo chambers, where we go to complain about demanding principle investigators (CSSSI), inscrutable professors (HLH17), boyfriend’s latest tantrum (Bass), the state of the country (Starr), section assholes (WLH), forty hours spent in the studios and weed legalization (Haas), and Brett Kavanaugh (Law).

By virtue of enabling inhabitants to share common experiences, these spaces foster a unique sense of community. The Gothic architecture makes Yale seem special to Type-A seventeen-year-olds on its admissions brochures, but these micro-communities form the mortar that actually holds this institution together. While tapping to AJR’s bops blasting in my ears and sipping my Tazo Awake English Breakfast tea, sourced from the little shrine to hot water, I continue to hammer out this essay. I am in the peculiar state of mind that loses regard for any sense of structure. At some point, a distraught friend walks in. We assume he is calling it a night and is here to say goodbye. Alas, he is headed for darker grounds: the Zoo. There are too many inside jokes in this essay I think out loud. There are too many inside jokes in the CEID, my friend rebuts. I am recursively entering my own story, in too deep, just like Racket*.

*Racket is a recursive programming language taught in CS 201: Introduction to Computer Science. Its uncanny compulsion to reference itself has been the bane of generations of students’ existence.

Surbhi Bharadwaj | surbhi.bharadwaj@yale.edu