Isabel Lee

“Moving to the U.S. was the great ‘gijeogwi’ of my existence,” I explained in choppy Korean, practicing with my mom the day before an oral presentation.

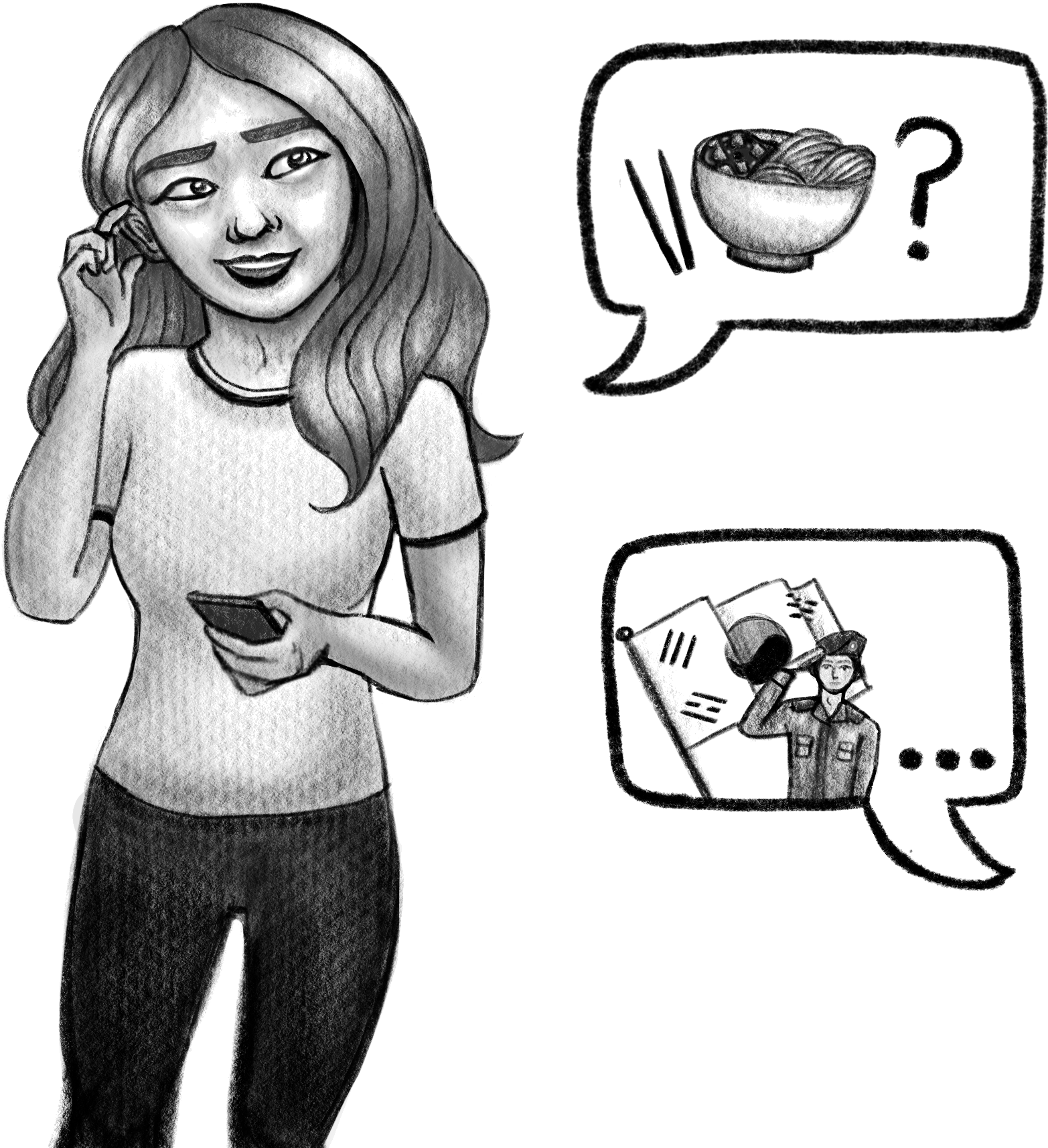

She laughed over the phone, “The great ‘diaper’ of your existence?”

It was a simple error — “gijeog” (miracle) versus “gijeogwi” (diaper) — the kind of mistake you only make when you have the language proficiency of a 6-year-old. Which was literally all I had. Like most Asian-Americans, my native tongue was the first language I learned, picked up lovingly from my mother’s lips and then promptly forgotten as soon as I discovered the social capital that English held in the suburban Midwest.

This is a choice that all “bye-lingual” students face when they come to Yale. Do we pick up a new language like German or Latin, or patch together the language we’ve lost? We call this latter option the heritage track. The “I can speak but not read or write” track. The “it was just easier to forget” track. We are generations of children who grew up believing that our native tongues were not worth holding onto.

In my first year at Yale, I was one of many students who thought that taking my heritage language was a cop-out. I didn’t want to study a language that my friends assumed I already spoke fluently or admit to myself just how far from fluent I was. So I took two credits of Spanish instead, satisfied that I had “gotten my language credits done.”

I didn’t reflect on this decision until last semester, when a friend pointed out that while my Mom texts me in Korean, I only respond in English. I hadn’t realized how strange it was that we communicate in this way, each person only understanding three-fourths of the other’s words. To entertain myself, I downloaded the Korean keyboard, only to realize that I didn’t know how to spell the words “I love you.” That’s when I decided to take a heritage language class.

It might seem easy to recollect words that the tongue used to wrap around comfortably. But the experience is more like cupping water in my hands and watching it slip out through my fingers. Sometimes, I don’t like to practice my Korean. The struggles of language learning aside, there’s a specific discomfort in being shoved up against something that I used to remember, used to know so effortlessly. Like the honorific words I used to invoke with my grandparents. Like learning how to spell the names of the foods I eat at home everyday, “miyeog-gook” and “jjigae,” and relearning our best kept secrets, untranslatable words like “han” and “dab-dab hae.” In many ways, language classes can’t help but teach culture. And for the heritage learner, these cultural lessons attempt the delicate and painful task of reconstructing memory.

Strangely, this process reminds me of when I was 3 years old and learning English for the first time. I remember being an English as a Second Language student and turning over the word “jeans” in my mouth, my first word in English. Slowly, I shed more and more of my native tongue until only the bare bones remained. The words for “thank you,” “I’m sorry” and “I don’t speak Korean.”

This story continues in Asian-American households across the country, and I refuse to believe that it’s pure coincidence or childhood laziness. I still recall the habitual pain of correcting every substitute teacher who puzzled over my Korean name. Their tongues shredding through the vowels, their confusion an unforgiving spotlight. I remember sitting at the dinner table, poking fun at my dad for pronouncing the word “fork” incorrectly. I remember teaching my mom how to say “thyroid” and “chemotherapy” while flinching with embarrassment at her accent. By the age of 6, the singular importance of English had been pressed upon me. I began to see the Korean language as a relic of a place that I had left behind.

Sometimes, I stare around my Korean class blankly as I learn seemingly useless words like “neon green” and “localized torrential downpour.” I get frustrated that I still don’t know how to say “important” words like “democracy,” “economy” or “compassion.” I get angry when I mix up words like “jeo-nyeog” (dinner) and “jeon-yeog” (military discharge). It feels personal. It feels like something that’s been assimilated out of me. My excavation is a slow one, one that requires me to reach into myself and wrench something out, often to discover that there is nothing left to hold onto.

In these moments, I remind myself why I’m sitting in the classroom, drilling colors and weather expressions into my mind. To learn how to tell my parents I love them. To learn how to write poems in my native tongue. I think about my grandparents’ house in Busan and the coffee shops on Garosugil, where I touched, felt, moved and failed to understand things. Where I had asked my mom what we were going to eat for military discharge, and she had not corrected me because she had long stopped believing that her daughter would ever want to learn again.

Dear Umma, thank you. I’m sorry. I don’t speak Korean. But I want to.

Sophia Nam is a sophomore in Ezra Stiles College. Contact her at sophia.nam@yale.edu .