Dustin Dunaway

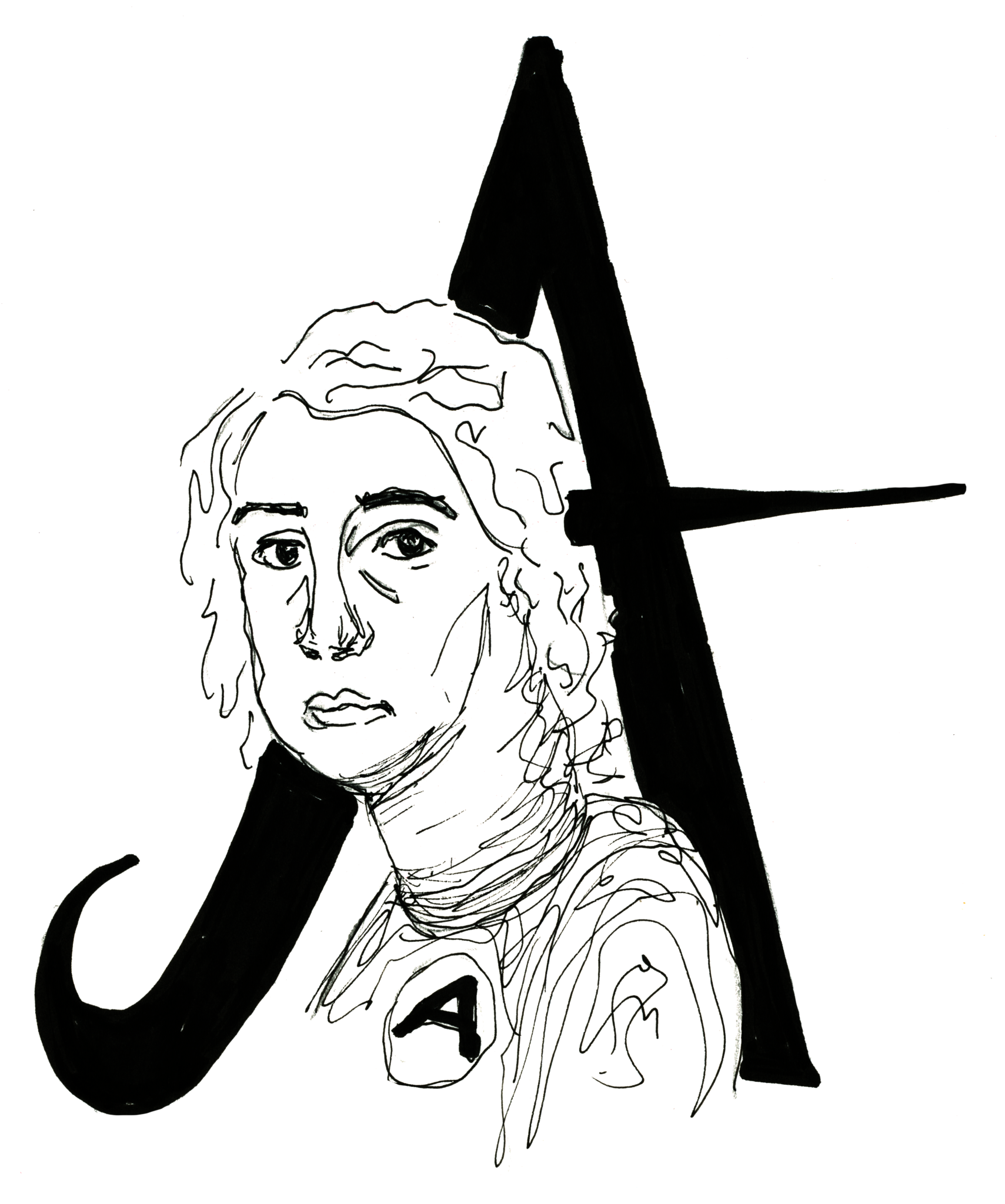

In staging Suzan-Lori Parks’ “Fucking A,” the Dramat is telling an old story. Or maybe it’s a new story made old. Or maybe it’s a story we can’t even call a story, a folktale grown too warped, too tired in the telling. When the play opens, we see Hester Smith framed in sharp light, played with caustic, simmering rage by an instantly-magnetic Alejandro Campillo ’21. Campillo is clad in gray sweatpants and a sweatshirt. A branded “A” on their chest peeks through the government-mandated hole in the fabric. The cast lies in wait around them on the periphery of the stage, heads down or turned to the side, facing the wall, frozen in swivel chairs, hunched over, standing like statues.

This setup remains unchanged throughout the play — characters enter and exit the action but remain always in view. When they stand to move, to speak, to enact and avoid violence, it’s almost weary. This story, that of gendered, sexual, racial oppression, that of motherhood and agonizing, unspeakable rage, has been told before, a hundred ways, a hundred different times. Never like this, though, and the puzzle pieces are ever-changing — director Adrian Alexander Alea renders each acutely fraught while playing with gender permeability in casting and double-casting.

“There ain’t no winning,” Hester tells us before the story begins, as the audience is still settling into their seats. We stay to watch anyway, despite the warning. Someone has to.

Inspired by The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne, “Fucking A” tracks Hester, a state-sanctioned abortionist, in her single-minded crusade to reclaim her son, Boy Smith, from what can only be described as the prison-industrial complex. He stole food from his employers as a child. Boy and Hester scrubbed floors for The Rich People, and their daughter, who grew up to be the Mayor’s supposedly-infertile wife -(The First Lady, an excellent Angela Barel di Sant’Albano ’20) told on him, effectively branding him a criminal.

Hester had a choice: prison or the scarlet letter. Because work as an abortionist meant an opportunity to someday buy her son’s freedom, she accepted her brand willingly, though she’d never wear it with pride. Baby-killer, she often calls herself. Her “A” grows more prominent throughout the play — it “weeps” and smells before she must perform an abortion, and, by law, she can never hide it. Campillo does superb physical work, all slouching, all hunched quiet before sharp, pressing bursts of fury; Hester wants revenge on The First Lady, and it’s too primal of a desire to hide. Meanwhile, a prisoner named Monster, played by an impeccable, measured Kezie Nwachukwu ’20, is on the loose, weaving in and out of the play’s central action. As with the other characters, Monster is, we’re told, what his name implies. Hester, Boy, Monster, The First Lady, The Mayor. An old story. Moving puzzle pieces. See it at the University Theatre this weekend, see it a thousand years from now.

Though the play is deliberately set in no particular time and place — Parks’ stage directions describe the story as “otherworldly” — Alea has, equally deliberately, chosen the 1970’s “Golden Age of Pornography.” Above the stage hangs a large, ruffled projector, almost-perpetually on “pause” during the action of the play — “pause” spelled in reverse, as though someone is watching from the other side of the screen. During scene changes, when the cast pushes worn-out furniture to the side in order to move more to the forefront, an endless, cyclical task, the 1972 pornographic film Deep Throat plays in the background.

Click goes the projector: we see the movie, graphic and uncomfortable.

Later, click: a colorful screen that indicates an old-school technological error, often framing characters as they perform a song, sometimes comical, always epithetic — Hester’s best friend, Canary Mary (Vimbai Ushe ’19, stunning and larger-than-life), the mayor’s mistress, sings about living in a “gilded cage.”

Click: the projector translates when characters speak in TALK, a fictional language that is used to voice the illicit — “the abortion” — and the unclean — Canary on The First Lady: “Her pussy is so disgusting, so slack.”

This is, in many ways, a story about culpability. When Hester attempts to secure a picnic with Boy, she’s blocked by a sputtering Freedom Fund bureaucrat (Annie Saenger ’19, taking on multiple roles) who informs her that the price, never firm, always dependent, has gone up again.

“It’s that rich bitch’s fault,” Hester spits before quietly conceding. This is too easy a narrative, of course, and the “rich bitch” is herself subjugated to endless posturing, endless verbal vitriol from The Mayor. Played with infectious, testosterone-fueled abandon by Tarek Ziad ’20, The Mayor, clothed in colorful button-downs, suit jackets, neat slacks, is masculinity gone rogue, proselytizing about his sperm and sexual prowess. The Freedom Fund never blames The Mayor, and Hester never blames the Freedom Fund. Her ultimate revenge on The First Lady, after believing Boy is dead, is a forced abortion of a child The First Lady had with Monster. The act itself happens offstage, a litany of muffled screams. When Campillo returns onstage, their hands are covered in dripping blood. Who’s responsible, Suzan-Lori Parks asks us. Who pays?

“I’ll get back at her,” Hester says, immediately before the act. “I’m not a mother otherwise.”

Part of the appeal of any Suzan-Lori Parks play is the language, the easy, if fractured cadence. Though Campillo speaks quickly, rapid-fire words almost a poem in the speaking alone, no character can match them; Ushe drags syllables out, Hester’s lover, Butcher (Zyria Rodgers ’21), pauses between words in a pages-long monologue. Only once Monster, also covered in blood, reveals himself to be Boy — “better a monster than a boy,” Nwachukwu says, and the audience inhales as a collective — does Hester find a linguistic match, and their words, hasty, almost cut each other in midair.

By this point, of course, it’s too late. The First Lady has snitched on Monster yet again (what has changed, in the becoming of Monster and the passing of Boy?). There are Hunters after him (aren’t there always?). He asks Hester to kill him, and she does, a quick cut of the neck that leaves him stretched out over her knee, almost tender, almost a dip in a waltz. From there, the whole stage is movement: the cast moves furniture backward, The Mayor settles into a couch, splayed out, facing the audience. It’s him who’s been pausing, unpausing, and we see it all, quick: click, Deep Throat, click, a bomb, click, fireworks.

The screen descends, hitting the ground with a dull thud. Click: static. Endless.

Nicole Blackwood | nicole.blackwood@yale.edu