Michelle Li

By the time I was in the third grade, I had been to the houses of many of my friends — all of whom were my classmates. Together we braved the hallways of St. Augustine, a Catholic grammar school an hour out of New York City by train or an hour and half by car (depending on traffic). Albeit a reputable school, Saint Augustine was small in enrollment: I was one of forty third graders, a number which was split into two classes, one taught by Mrs. Matra, one by Mrs. Herbek.

Our mornings in Mrs. Herbek’s class all started the same way. At 7:45 a.m. we were led from the school lobby down to our classrooms, we visited our lockers — third grade was the first year we could use both the long rectangular locker and the supplementary square locker above it — and walked into our classrooms, where we worked on various spelling exercises and math problems to be completed by the first bell, which rang promptly at 8:20 a.m.

It was at one of these morning moments that the Catholic essence of our grammar school curriculum was made apparent. Before reciting the pledge of allegiance, in a sequential pattern I still believe to be intentional, we would stand, put our hands together, and pray. There was certainly some spontaneity involved, more so than you would imagine. As the prayer was not projected over the school’s loudspeaker, each classroom said a different prayer at the teacher’s whim. Some days we said the Our Father, some days we said the Hail Mary, and if our teacher felt we had been behaving poorly in homeroom, we would ask for Jesus’ forgiveness in reciting the obsequious Act of Contrition.

My daily schedule changed every year with the new teacher, and in my 14 years of Catholic school, third grade was the only year in which my first class of the day was religion.

The concept of a daily religion class is familiar to those who attended a religiously-affiliated, sectarian school; intuitively understood by those who attended a non-sectarian private school, public school, or the like. For those who fall into the latter category, an explanation regarding these classes is in order.

Religion class is generally structured the same every year, with the caveat that each year delves deeper into the same material. The first weeks, we would talk about grace — the idea that god favors us, his creation, without any deserved reason or merit from our end, an idea particular to the Christian conception of deity — then we expand to the early teachings of Moses, most importantly the Ten Commandments, a direct “gift” from god. We would round out the Old Testament’s greatest hits — Abraham’s covenant with god, Noah’s covenant with god, some burning bushes, etc., until that controversial baby rendered his head out of a virgin.

Yet, I would grow disinterested every year by the time we finished the Moses section, clad with his two tablets. So the story goes, Moses schlepped his way up Mount Sinai — located both in Biblical and modern Egypt — and spoke with god, who gave him the Ten Commandments. Few have questioned an elderly man’s ability to climb a mountain over 7,000 ft. high (although Moses himself is considered a legendary character, not a historical one, by most scholars), but that is, I suppose, beside the point.

Various Abrahamic religions and sects of Christianity order the Ten Commandments differently, but the Catechism of the Catholic Church — a sort of “greatest hits” of every Catholic belief — has long maintained adultery to be the Sixth Commandment. I felt confident that I had understood the meaning of the commandment, given my comprehensive first and second grade education, but it was that day in Mrs. Herbek’s third grade class when I discovered that many Catholics consider marriage after divorce a form of adultery.

This, however, wasn’t the ignorant biblical interpretaton come to by two millennia of white men. It did not come from the Vicar of Christ, rather, Christ himself, “To the married I give charge, not I but the Lord, that the wife should not separate from her husband (but if she does, let her remain single or else be reconciled to her husband) — and that the husband should not divorce his wife” (1 Cor. 7:10-11).

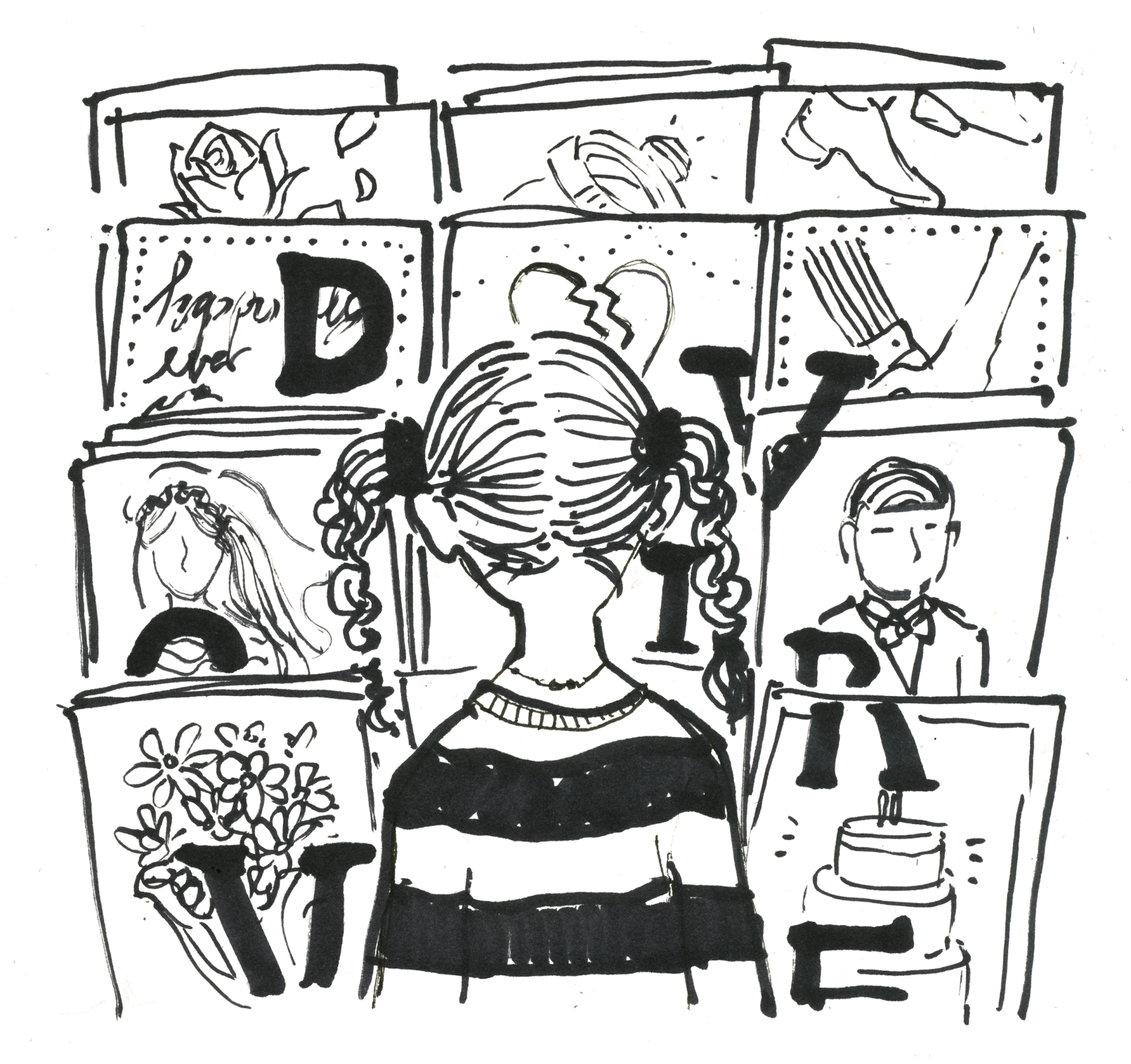

I had been to almost all my friends’ houses, and they had all fallen into the Hallmark family structure promoted by American and Christian tradition — two parents, a child or two, maybe three, a domesticated animal. Thus, such experiences made that particular third grade religion lesson uncomfortable for me, the son of two adults with six divorces between the two of them.

~

A former girlfriend once described my conception of marriage aptly: “Nick doesn’t believe in marriage; he believes in divorce.” It had been more than a decade since my third grade classroom, which I have at present switched out for a college dorm in a non-sectarian institution. Six aggregate divorces had jumped to seven, a subtle, unconventional brag I wear on my sleeve.

I was recently given a prompt in a writing class, in which we were asked to write a rousing review of an entity that most would not consider positive, so I defended divorce in the best 300 words I could muster up. Rather than speak of the matter from the perspective of an old boy on the cusp of manhood (a position I would like to believe I am currently in), I thought back to that third grader, unsure of his family circumstances for the first time in his life.

That boy understood the long rides every other weekend -— forty minutes from Croton-On-Hudson to New Rochelle — as the status quo, remembering with glee the once-a-week trips to Barnes & Noble with his father. Our weekends and Wednesday’s were a combination of my parents’ solemn signatures atop a stack of legalese and my father’s regretful love.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church claims that divorce, “brings grave harm to the deserted spouse and to children traumatized by the separation of their parents and often torn between them.” Yet, both in reflection of those early years and upon reflecting on my entire childhood, I could not disagree more fervently.

My reflection on the earlier years having separated parents provides a more shallow analysis of the situation. As I wrote in my recent piece regarding those years, “If your parents are busy, you will find yourself alone. If one of them is a shit parent, you find yourself with one good parent, and if both your parents are shit, you’re really fucked. Multiple birthdays, double the Christmas, twice the house.” A bit jocose, I agree, but the maths add up: divorce has created, at least in my instance, a world in which I have the love and support and perks of many adult figures, all with their extraordinarily varying wisdoms and guidance.

Taking a holistic approach to the matter, incorporating my whole twenty year childhood, I come to a similar conclusion, albeit by different means. The predictable struggles arose for my two sisters and me: the squabbles between the various parents, involving at times up to 4 or 5 parents at once. There was an ever-present tension between the two groups of parents, who all knew that their escapist children could flee inter-familial problems and just show up at another house, where they would be greeted, welcomed by another pair of loving parents.

But despite those arguably petty issues, there was never a moment in which, using the Cathecism’s words, I felt “traumatized” by my parents’ separation. I felt nothing, which may first imply my lack of emotion, but I have few words to say given my nonplussed attitude toward my parents’ separation. Despite my being American, the British Office of National Statistics found that 82% of 14 to 22 year olds would prefer their parents separate than “stay for the kids,” and it is commonly understood that raising children despite a divorce is trivial and can be easily done.

~

The doubt, however, still remains regarding the future. I have not just coped with my childhood; I have justified and appreciated it. As has been implied by my tone, I was, am and ostensibly will always be irreligious, to the dismay of Mrs. Herbek and the rest of my third grade class. Yet, the words “Nick believes in divorce” ring a certain truth, to the extent at which I have begun to plan on its results.

A column from two weeks ago touched on the justifications for or against having children. A heartfelt and well-thought-out column, the author pushed and pulled on the concept of a conventional family structure, coming to the ultimate conclusion that yes, procreating is justified and good. And with this perspective in mind, I have begun at the ripe age of twenty to consider divorce from the parent perspective.

I have been raised to understand that the traditional family is superfluous, good for continuous participants in the yearly holiday photo, but wholly unnecessary in raising good, happy, non-traumatized children. And despite my 300 word rousing defense of divorce, no matter how much I believe in my childhood as being good and stereotypical, and happy and full, I am utterly unfamiliar with the benefits of modeling yourself and your romantic life after the joyous, continuous “til death due us part” love between the two people who cherish you most. Even though I remained untraumatized, what of my own children? Although I sit here only a score old, wholly without the ability to imagine anything about my children other than their names, without knowing how I will love them, I wonder how they will feel, how they will react to their parents getting a divorce.

While I wish them well in forethought, I do not know if they will want the Hallmark family I never wanted nor needed, and the idea that I will most likely be taking them to Barnes & Noble every Wednesday and hosting them every other weekend breaks my heart in a way I cannot understand fully yet, in a way I know will shatter my life, if not theirs.

Nick Tabio | nick.tabio@yale.edu .