Two Yale alumni, Eric Stern ’03 GRD ’07 and Aleksandar Vacic GRD ’12, have created a new diagnostic tool that can determine the correct antibiotics with which to treat infectious diseases with more speed and accuracy than current technologies allow.

The duo, who met as graduate students while working in Yale engineering professor Mark Reed’s laboratory, set out to tackle infectious disease diagnostics in 2014 when they founded SeLux Diagnostics, Inc. Their breakthrough personalized medicine therapy determines precise antibiotics to prescribe to infected patients up to three days faster than the industry standard, according to a September 2018 press release by PRNewswire. Because of their targeted approach, infectious bacteria are less likely to grow resistant to the prescribed antibiotic — addressing the pressing issue in medicine of antibiotic resistance.

Melinda Pettigrew SPH ’99 — Yale School of Public Health senior associate dean of academic affairs and professor of epidemiology — told the News that antibiotic resistance is an inevitable phenomenon that posed a problem for healthcare providers soon after antibiotic use first became widespread in the 1940s.

Because of antibiotic resistance, Pettigrew said that medicine is running out of effective antibiotics that healthcare providers can use to combat both common and severe infections. Due to longer hospital stays and higher mortality, antibiotic resistance costs the U.S. healthcare system upwards of two billion dollars a year, she said.

As of late, it is sometimes difficult for doctors to differentiate between bacterial and viral infections with current diagnostic tests. Pettigrew said that this leads to the inappropriate prescription of antibiotics for common respiratory infections that may have been caused by a virus, which bacteria-targeting antibiotics cannot destroy.

“If you come into the hospital and you’re sick, [doctors] may not know exactly what you have and the susceptibility of your pathogen at the time — they may want to get you on antibiotics quickly,” she said. “If we had better diagnostics that would make a significant dent in antibiotic resistance.”

This issue is a personal one for Stern. When he was in the 3rd grade, Stern’s grandmother nearly died after acquiring an infection that led to sepsis — an extreme, potentially fatal response to an infection. He told the News that doctors could not quickly find the right medicine to treat her illness. The same hospital that took care of his grandmother has had the same diagnostic tools since the 1990s, which Stern said is “exciting for business, but infuriating on a human level.”

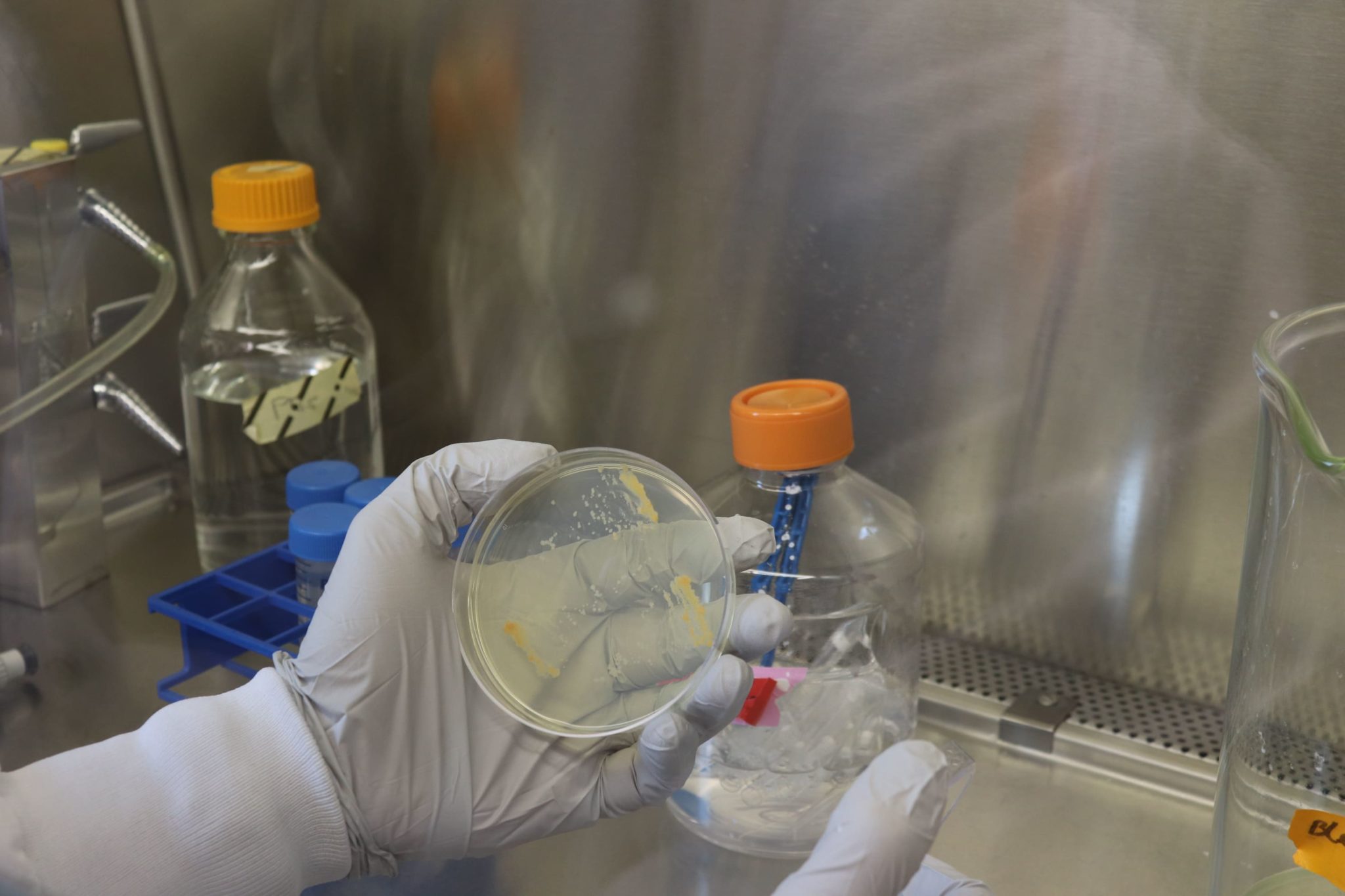

Now, Stern has set out to design a rapid diagnostic test that will help doctors as they develop treatment plans for their patients with infectious diseases. The program will determine a specific antibiotic in a matter of hours — versus the typical three to five days — that is best able to fight off the infection. The company tests for 60 different drugs — every drug currently available.

He told the News that because patients would be using the most effective antibiotic to treat their infection, resistance to a particular medication would become less frequent. These targeted antibiotics can more effectively kill the bacteria, lowering their chance of mutating and developing resistance to the antibiotics.

“A doctor will be able to rest assured that he or she will have have results for all drugs, at the same time, the day after a patient comes in,” Stern said.

The team has set their sights on clearance from the U.S. Federal Food and Drug Administration. They plan to start the process in the latter half of this year and hope to receive approval from the agency by next spring.

Stern credits a great deal of his success to his time spent at Yale. He said that he had access to “the best professors” in multiple different STEM fields who were “very interested in helping teach students.” Stern received a double undergraduate degree in Chemistry and Electrical Engineering and earned his graduate degree in Bioengineering and Biomedical Engineering.

“I was [given] the incredible opportunity to work closely with professors at the highest level in different disciplines,” he told the News. “This enabled me to [bring] people [from different] disciplines together [in my current position].”

In 2003, Stern broke the Yale undergraduate record for the most classes ever taken by an undergraduate student.

Skakel McCooey | skakel.mccooey@yale.edu

Marisa Peryer | marisa.peryer@yale.edu