Designed by Maggie Nolan

Despite the long-standing push from student activists to divest from fossil fuels, Yale still has a direct stake of $78 million invested in Antero Resources, a natural gas producer with operations in the Appalachian basin, according to a Sept. 30 Securities and Exchange Commission filing.

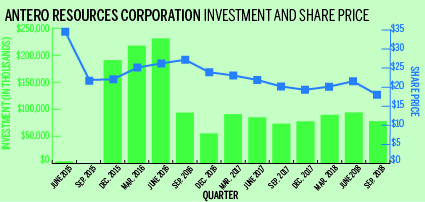

The quarter’s filings, released in November, indicate a 17 percent decrease in the University’s holdings in Antero Resources as the company reaches its lowest-ever stock price. Still, the filings, revealing the University’s continued direct investment in the natural gas company, arrive amid a renewed effort by student activists to push Yale to reaffirm its commitment to address climate change.

“The current U.S. national administration is methodically working to reverse progress made by the previous administration on climate change, and worse,” said epidemiology professor and fossil fuel divestment advocate Robert Dubrow. “But the physics of climate change tells us that the coming decade is critical. Thankfully, many state and local governments, corporations and nonprofit institutions, including universities, have recognized the need for bold action, including divestment. If there were ever a time for Yale to divest from fossil fuels, including natural gas, this is it.”

University spokesperson Tom Conroy and Chief Investment Officer David Swensen did not respond to request for comment. Per University policy, Yale does not usually comment on its specific investments.

Antero uses hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, to extract natural gas from shales in West Virginia and Ohio. Fracking uses significant amounts of water and chemicals to pierce previously impenetrable rock in order to obtain natural gas. The process has garnered criticism for its role in imbuing harmful chemicals in the water supply and expediting climate change. Antero has committed 14 environmental violations and racked up over $1 million in penalties since 2011, according to documents from the Environmental Protection Agency.

SEC filings indicate that the University first began investing in Antero in 2015 and continues to hold millions in its stock. The filings show that as of July 30, the University held more than 4.3 million shares in Antero. Its investments in the company peaked at $230 million in July 2016. But as the stock price decreased, the University sold many of its shares. Since then, the University’s investment in Antero has hovered around $80 million.

Yale’s stake in Antero was revealed in the University’s 13F Forms to the SEC. The quarterly report is filed by institutional investment managers that oversee assets of over $100 million. Yale, which invests the majority of its $29.4 billion endowment through external investment managers, only discloses to the SEC the investments made directly by staff in the Investments Office. The assets disclosed in the latest 13F filing, including the Antero holdings, amount to $575 million, just two percent of the University’s total investments.

Last month, over 1,000 members of the Yale community signed a letter to University President Peter Salovey requesting that the University “redouble its efforts to engage with the serious problem of climate change.” Student and faculty activists interviewed by the News expressed frustration that the University continues to invest in the natural gas producer.

“It is pretty clear how fracking contributes to environmental harm, especially to historically underserved or marginalized communities whose land fracking companies want to drill into,” said Sophie Lieberman ’21, a member of Fossil Free Yale. “For Yale to be invested in it shows that [the University] does not care about this type of harm. It also undermines the research that Yale actively promotes, that Yale professors are doing into the environmental and health impacts of fracking.”

In 2014, the Yale Corporation voted against divesting from fossil fuel companies, citing difficulty in identifying the extent to which fossil fuel companies are a true threat to the environment.

According to a 2014 statement, the Yale Corporation Committee on Investor Responsibility — the body that presents the Corporation with policy recommendations on ethical investing — stated that it does not believe that divestment is the most effective way to tackle climate change.

“CCIR agrees that climate change is a grave threat to human welfare,” the 2014 statement reads. “We believe, however, that […] divestment or shareholder engagement as a precondition to divestment are neither the right means of addressing this serious threat nor would they be effective. Yale will have its greatest impact in meeting the climate challenge through its core mission: research, scholarship and education conducted by its faculty and students.”

Still, the Investments Office has taken steps to “account [for] the full costs of climate change,” according to a statement on its ethical investing policy published on its website. In 2014, Swensen sent a letter to all of Yale’s active external investment managers urging them to incorporate costs of carbon emissions in investment decisions. Swensen wrote that investments with small greenhouse gas footprints should “be advantaged” relative to investments with large footprints.

In an April 2016 letter to the campus community, Swensen announced that the University sold $10 million of its investments in three publicly traded fossil fuel producers whose positions did not align with the University’s own ethical investments policy. Still, the University continued to invest in Antero.

Lieberman — who called for the Yale to fully divest from fossil fuel companies — expressed disappointment that the University continued to invest in Antero despite Swensen’s 2016 letter reaffirming his office’s commitment to responsible investment.

Currently, the University is investing almost $150 million less in Antero than it did two years ago. Nir Kaissar, founder of an asset management firm and a columnist for Bloomberg, speculated that the decline in the University’s stake in Antero was a result of the falling price of shares or “socially-related considerations.”

According to Charles Skorina, an expert on endowments, if the University were to gradually divest from fossil fuel companies, it would be incentivized to keep its divestment silent.

“It’s like a game of poker. If Yale sells, a lot of people will try to buy cheap or bet against them,” Skorina said. “From the perspective of an investor, Yale wouldn’t want to publicly say that they are divesting to not suffer the losses.”

Other universities, including Harvard University, have previously invested in Antero. On June 30, 2016, Harvard held direct shares in the natural gas provider but sold all of them the next quarter.

Lorenzo Arvanitis | lorenzo.arvanitis@yale.edu