Tiffany Ng

There’s literally only four traffic lights in the whole of the city.

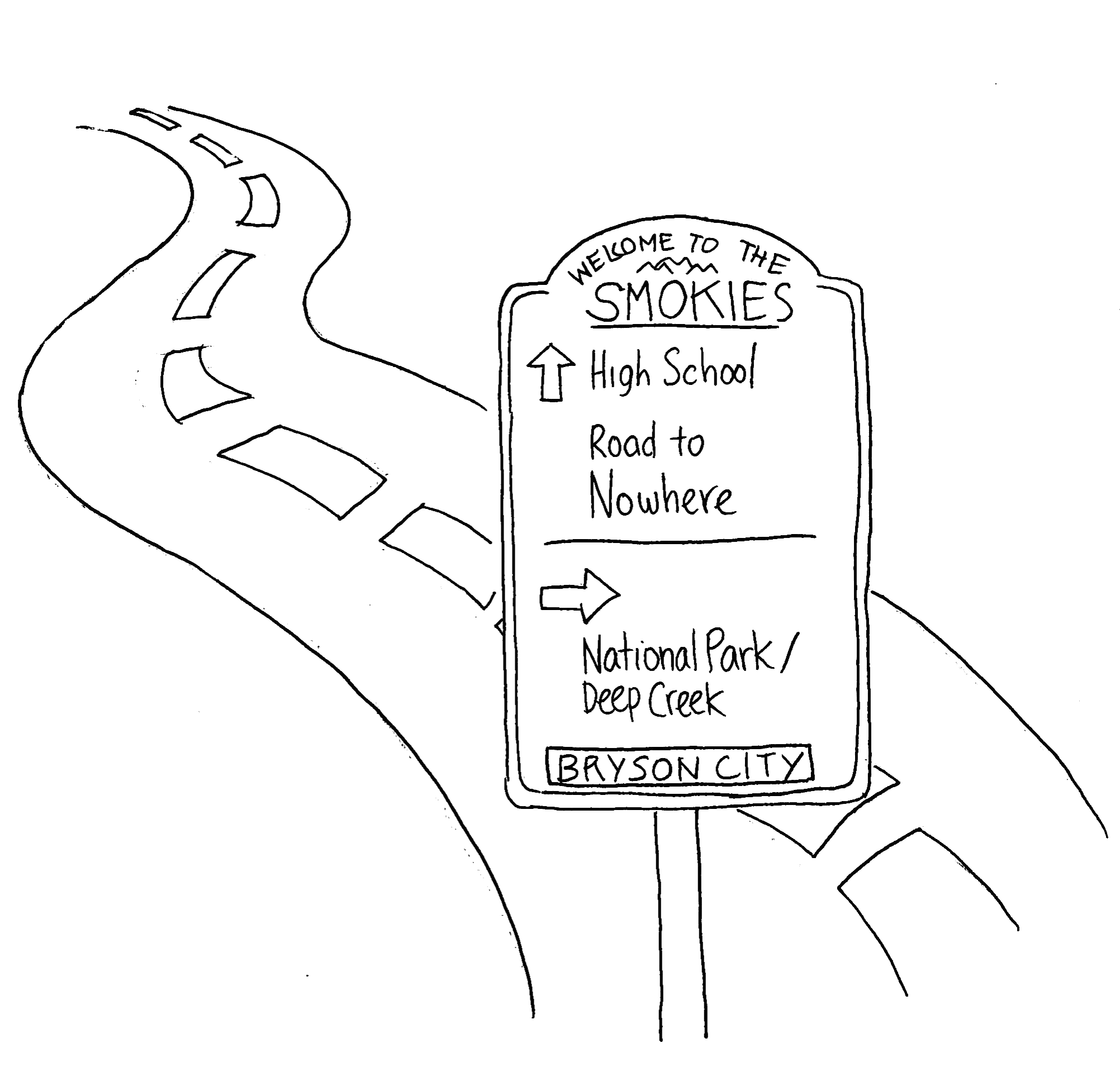

Having grown up stuck in traffic and jaywalking across highways, where the sheer abundance of traffic lights, cars and miscellaneous road signs have rendered traffic etiquette obsolete, Bryson City, North Carolina, was definitely a new sight to see.

Hong Kong, though 474 times the size, has the roughly the same population density of Bryson City. We cityfolk value variety, but we often forget about the blissfulness of simplicity. I for one, in my 18 years of existence, have never been able to walk through a town in 20 minutes. Strolling through Everett Street, the SoHo of Bryson City, my response as I approached the end was, as The Strokes so eloquently put, “Is this it?”

The quaint formation of small single stories stores lined up next to one another down a horizontal street seemed outlandish to me. Where were the towering shopping malls? The larger-than-life LED billboards?

As Emma, my dear friend and neighborhood tour guide, explained the histories of different shops, their locations, name changes, etc., it came to my realization that Hong Kong’s ever-changing geography, in the unveiling of new skyscraper on Mondays and the grand opening of a new mall on the occasional Wednesday, created a concept of “home” that was ever-changing. There is no “that’s where I got my first job as a barista” or “that’s that ice cream shop I always went to after school with friends.”

The inability to mourn your favorite store closing down is, in itself, sorrowful. I’ve always wanted to be a regular at some form of establishment, to have the ability to walk into a restaurant and say “the usual, please.”

This simple aspiration of frequenting a single store is, in my opinion, reflective of Hong Kong’s predominantly capitalist regime. Unattainable in a sense where the sheer commercialisation of local stores have made the regular turnover of staff an industry standard, the inability to develop personal relationships with a single store reflects the “death to diversification” the South China Morning Post described in a recent article about capitalism in Hong Kong. With the rapid commercialization of the Hong Kong economy to blame, the elimination of these small, mostly family-owned businesses have fostered an environment. When your favorite boba place closes down, instead of mourning your loss, all you have to do is walk three blocks down either direction to find its identical chain brother.

We carried on the day with a visit to Ingles, where, for the first time, I witnessed someone running into someone they knew at the supermarket.

Supermarkets, I thought, would be the same in both small towns and large cities, being owned by the same franchises and carrying the same products. But what differed wasn’t just the merchandise, but the experience of going into a supermarket itself. Back home, shopping in a supermarket was more or less a solitary activity. With headphones in and a short list of things to pick up, supermarket shopping in Hong Kong is simply a get-in, get-out kind of experience. Supermarkets in Bryson City, however, were nothing less than vibrant social hubs. Running into familiar faces seemed inevitable, you’d see Patsy from yoga at the fresh produce corner, Cassidy from high school in the condiments section and Jesse from the local coffee shop at checkout.

Not only am I not a distant relative to the daughter-in-law of someone twice removed from my neighbor’s family, but despite being physically meters away from people I’ve lived with my whole life, I’ve never spoken to them. It’s funny, how Hong Kong’s miraculously timed, systematic pace fosters an isolating environment where being geographically close means anything but being socially close … but why?

A 2011 study suggested that living in urban area “means more social stress — or coming into contact with tons more people on a daily basis” which then “means having less control over an increased amount of interaction with strangers.” I can imagine, working a nine-to-five job on top of dealing with a god-awful boss, that any sleep-deprived individual would, at all costs, try to avoid any unnecessary form of stress (human interaction).

Maybe that’s why knowing every individual in town on a first-name basis helps with social anxiety. Your life is basically an open book that people within a two-mile radius of you reference and study through PTA coffee mornings, extended family luncheons and supermarket small talk. It could, to an extent, be stressful in its own way, having to remember the names of all of Pam’s seven children, or the amazing soda deal that Greg got at the supermarket the other day.

Sitting in the backseat of Emma’s mom-mobile (Taurus X) as she drives with her dad sitting shotgun, I found the constant stress-inciting bickering quite entertaining. I mean, it really doesn’t matter if you’re a bad driver here because there are few-to-no cars in the road for you to run into. I have this theory, that the biggest difference between rural small town life and urban city life is a car.

Being what The Atlantic describes to be a “transition from childhood and dependence to adult responsibility,” sitting next to a driver that didn’t ask about my future career aspirations or nag me about getting a boyfriend was, oddly enough, unsettling. Having always dreamed of going on impromptu road trips and drives into the sunset, I believe my personal assimilation of driving with the American Dream stems from the sense of freedom it represents. Particularly prominent images of teenage, American life ranged from what The Atlantic describes as “the ritual of being picked up for a date and making out while ‘parking’” to “cruising down Main Street to meet with friends and compete with rivals.” There was just something about getting to places without a MetroCard or a pre-routed public transport system that just screamed independence. As Emma blasted music and rolled down her windows, I felt like I was Sam from “Perks of Being a Wallflower” riding in the back of a pickup truck. In that moment, we were, indeed, infinite.

Disparate at first glance, as I gave into indulging in the countryside, it slowly dawned on me that rural small town life isn’t that different to urban city life.

Hong Kong’s imminent absence of physical interaction prompted a rather unconventional form of social exchange, nonverbal communication. The thin walls that separated me from my neighbors also exposed personal details, they created a culture where you’d learn about your neighbors’ most intimate secrets before knowing their first names. Living in high-rise apartment complexes really is a guessing game. You’d wonder, ever so often, who blasts “Die Hard” every Saturday night in Flat A and who, bless their heart, attempts to practise trombone in Flat B.

While “community” in North Carolina may mean having your best friend’s aunt’s Weimaraner give birth to the local outdoors shop owner’s pup who also happens to be the dog printed on their logo shirts, “community” in Hong Kong is something along the lines of a silent nod to your long-time neighbor as you enter the elevator in the morning. It’s sort of like the way your Asian mom never explicitly says “I love you,” but instead slides a plate of freshly cut fruit into your bedroom door as you study. This unique sense of community is never explicit, usually implicit, but always imminent.

Tiffany Ng | t.ng@yale.edu .