Joan Marcus

I had never seen the Yale Repertory Theatre stage so naked as in the moments that I waited for Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne’s “The Prisoner” to fill the stage on Wednesday night. There were no curtains, no cyclorama and no pre-show music. There were only the pitch-black bones of the Yale Rep’s stage, warm yellow light, a few tree branches, scattered dirt and dust and an estranged tree stump, worn and waned by the wind. The stage was vast and raw — not empty — but hungry for bodies to fill it. And when Hayley Carmichael, playing the Visitor, first entered and began telling the story of a man who sits alone in front of a prison for many years, the stage was filled with her easeful, captivating presence.

In the program notes of “The Prisoner,” James Bundy, artistic director of the Yale Repertory Theatre and dean of the School of Drama, recognizes Peter Brook as the “greatest living director and theorist simultaneously.” In his 93 years of life, Brook has directed over 70 productions and is the mind behind some of the most influential dramatic theory, like “The Empty Space,” in the 20th and 21st centuries.

In 1974, Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne embarked on their first collaboration together: a production of “Timon of Athens” at the Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord in Paris. Estienne, who worked as a journalist and theater critic before working with Brook, cast the production of “Timon,” and since then, has collaborated with Brook on countless productions as a casting director, co-writer, costumer and more. She is the powerhouse behind him and is one of the greatest unsung heroes of modern theater. Forty-four years after the pair’s debut production of “Timon” at Bouffes du Nord, “The Prisoner” premiered on the same stage.

Brook and Estienne’s signature ability to distill storytelling to a potent, immediate and alive experience was palpable in the moments before “The Prisoner” even began. David Violi’s set design and Philippe Vialatte’s lighting design transported the audience into a space that could be anywhere, but was not nowhere. When the actors did eventually fill the stage, their bodies were clothed with minimalistic, relatively modern costumes. Dark wash jeans, a button-down shirt. A black tank top, black trousers. The five-person cast hails from five different nations. Costumed in this minimalistic garb, they could have been people of anywhere, and were definitely not people of nowhere. The dedication to minimalism in design created space for the actor’s own bodies, faces and eyes to captivate the attention of the audience. And captivate the audience they did.

The acting in “The Prisoner” is nothing less than masterful. Hiran Abeysekera, who plays Mavuso, demonstrates the most incredible range of human emotion over the course of the 70-minute play. Mavuso kills his father after finding him in bed with his sister, Nadia, with whom Mavuso is also in love. For the remainder of the play, Mavuso must grapple with his own criminality, his broken heart and his eternal punishment: living outside of a prison building as a prisoner. It is impossible to look away from Abeysekera. The focus in his wide eyes is penetrating, and the way he uses his body, scaling up the walls of the Yale Rep stage in one moment, creating a pet rat with his fidgeting fingers the next, is magic.

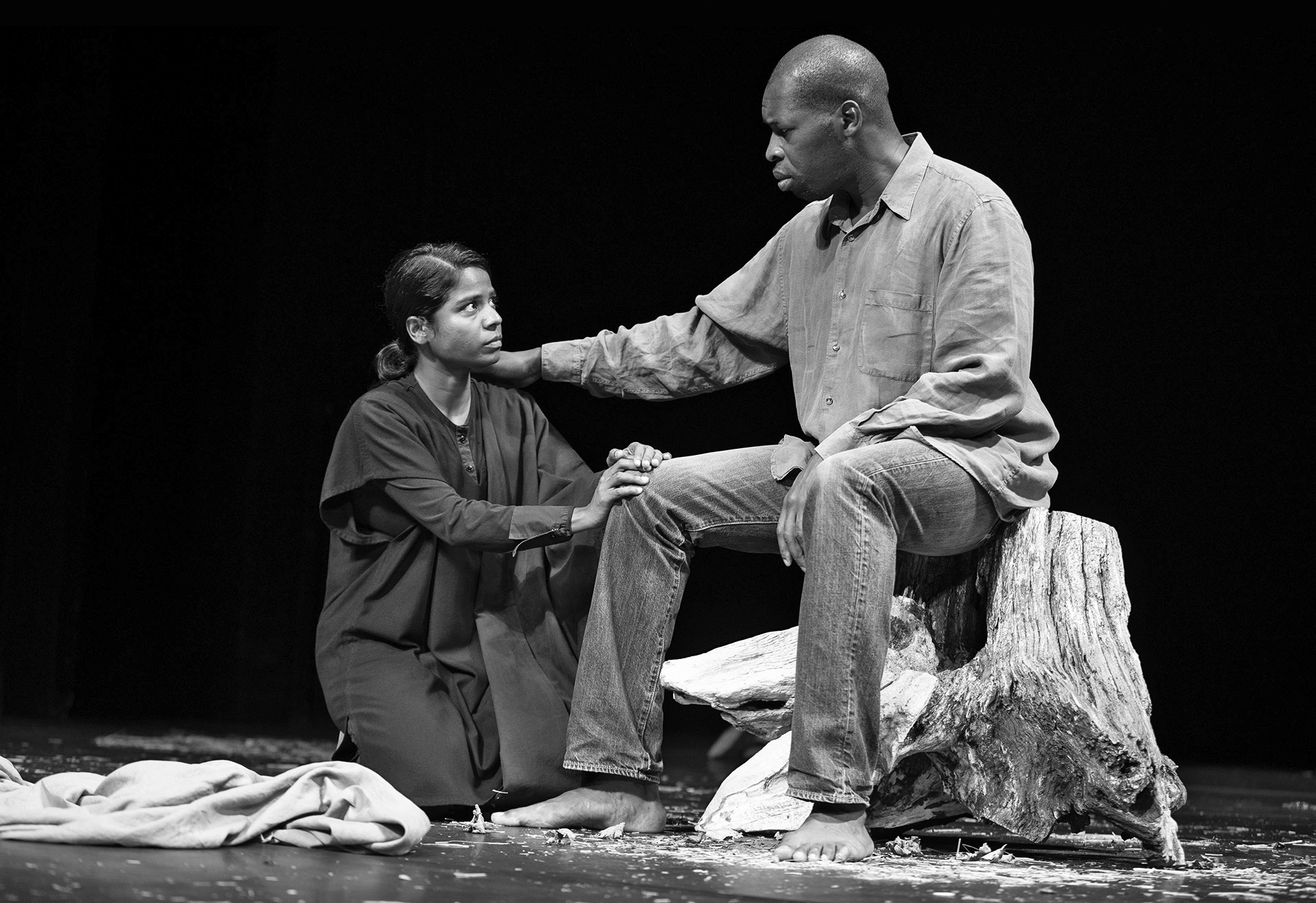

Herve Goffings, who plays Ezekiel, Mavuso and Nadia’s uncle, is beautifully powerful and draws a stark contrast to Abeysekera on stage visually and vocally in his sturdy frame and booming voice. He is a steady presence, threading each character of the play together. His relationship with Mavuso is confused and dark, though his relationship with Nadia, played by Kalieaswari Srinivasan, is tender and gentle. His relationship with the Visitor is desperate and heartbreakingly obstructed.

Both Srinivasan and Carmichael show impressive range not only in their own characters of Nadia and the Visitor respectively, but also in their performances as prison guards who share drinks and stories with Mavuso. Omar Silva, who plays Man and Guard, also shows masterful range in transforming from the person who beats Mavuso in prison to the person he befriends once Mavuso dwells outside of the prison.

The text of “The Prisoner” is incredibly sparse and ambiguous. Brook and Estienne weave together various tales, fables and allegories to tell Mavuso’s story. The text offers few answers and asks many questions of punishment, of atonement, of peace and of outsiders. The play invites the audience to explore and grapple with these questions alongside the actors, directors and writers.

Since premiering in Paris, “The Prisoner” has traveled to such prestigious venues as the National Theatre in London, the Ruhrfestspiele Recklinghausen festival in Germany and now the Yale Repertory Theater. Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne’s “The Prisoner” is jolting, important, tender and human, but most of all, it is staying.

Ryan Benson | ryan.benson@yale.edu .