One of the most important concepts in Judaism is the observance of Shabbat, the day of rest from Friday evening to Saturday evening. Whether that be a strict observance according to Jewish law or just taking a moment to unwind, Shabbat — or the weekend in general — is a time for rest and peace. Two weeks ago, our Shabbat was shattered by the Pittsburgh shooting.

Joyce Fienberg, Richard Gottfried, Rose Mallinger, Jerry Rabinowitz, Cecil Rosenthal, David Rosenthal, Bernice Simon, Sylvan Simon, Daniel Stein, Melvin Wax and Irving Younger were violently gunned down by alt-right extremists during Shabbat services in Pittsburgh.

This act was an anti-Semitic hate crime. Tragically, this is not the first mass shooting motivated by racial hatred in America, even though we pray that it will be the last. Typically at Yale, in the wake of a tragedy like this one, there is an outpouring of support alongside anger. Whether this be in the form of public Facebook posts, private messages to friends or community organizing, there is usually no shortage of Yalies decrying this kind of violence and the underlying buildup of prejudice that creates and fuels it.

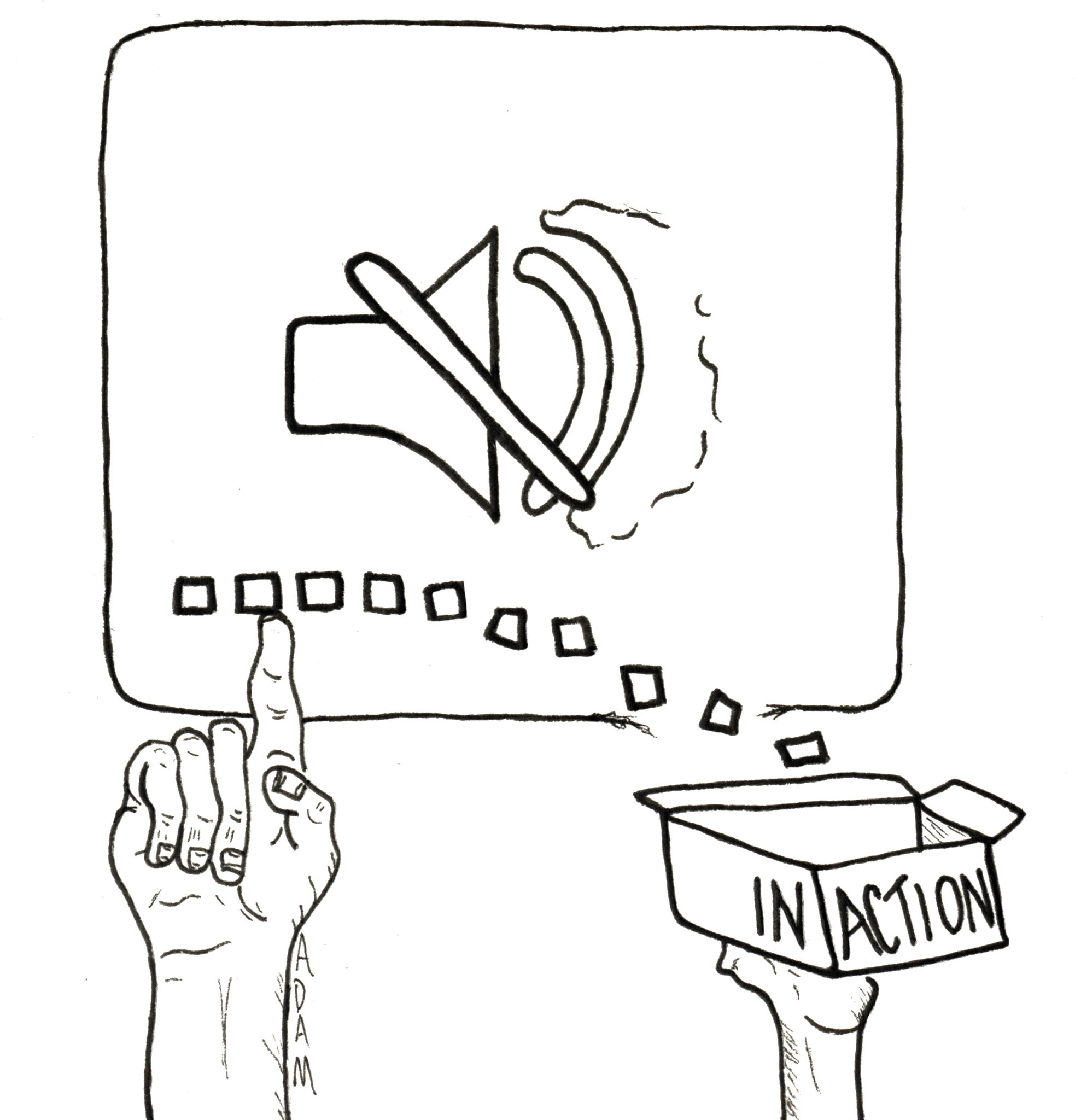

There is, however, a disturbing lack of this same response for the Jewish community at Yale in the wake of the Pittsburgh shooting. While my Jewish friends and acquaintances have been looking out for each other, there is a stark silence from everyone else on campus. The usual voices of campus activism, which decry gun violence, racism and prejudice of every kind are noticeably silent. I haven’t personally noticed any public or private show of concern for this shooting from non-Jews or similar instances of anti-Semitism: anti-Semitic vandalism of synagogues following the shooting, the vilification and bomb threat against liberal philanthropist George Soros, or the fact that record-breaking numbers of Holocaust deniers are openly running for office. The Yale administration has also reflected this same silence.

This silence is anti-Semitism at Yale, anti-Semitism that often goes unnoticed. Yalies pride themselves on their activism, fighting for communities that are marginalized and underrepresented. My hope is that this activism would more readily include the Jewish community at-large in the battle against anti-Semitism. I am not arguing against prioritizing issues that are closer to home, nor am I arguing that there aren’t communities which face both different and severe injustices relative to those of the Jewish community. For instance, it’s important to acknowledge that black and brown communities are much more susceptible to police brutality than I am as a white Jew. Prejudice takes on many different forms, all of which are hateful and should be condemned.

Even so, one form of anti-Semitism is being vocal about every other major tragedy while choosing to be selectively silent when the victims are Jews. This is rooted in the erroneous belief that Jews do not experience discrimination in America or elsewhere. But just because discrimination against Jews looks different than discrimination against other groups does not mean that it doesn’t exist.

Anti-Semitism at Yale takes many different forms — selective silence is just one of them. Another form of anti-Semitism is the lack of dean’s excuses for religious observances, which specifically affects Jews observing a series of holidays during the beginning of the fall semester — forcing students to argue with their professors, especially when participation grades are involved. Yalies make Jewish-coded references to the shadowy donors of the Joseph Slifka Center for Jewish Life at Yale. Yalies with no personal ties to Israel-Palestine take a hard stance condemning the existence of Israel without understanding the complex history of the conflict, while justifying similar human rights abuses in other countries — an act that falls within the definition of anti-Semitism by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. Other Yale Daily News op-ed writers have also written excellent pieces outlining other ways anti-Semitism plays out at Yale, such as Avigayil Halpern’s ’19 “Anti-Semitism is alive and well.”

If there is a silver lining in all this, it is that the solidarity and support from the Jewish community both at Yale and elsewhere has been overwhelmingly sincere and appreciated. This is also a public thank you to members of the Yale community, such as Chaplain Sharon Kugler and other spiritual leaders on campus who have made themselves available for support during this time. A few non-Jewish voices — notably Lauren Chan ’21 in “Standing and sitting together” — have also made themselves heard. We appreciate these voices wholeheartedly.

When Yalies speak out about every tragedy and issue that is dear to them, they are acting on the pursuit of justice, and for that, I have the utmost respect. When Yalies omit their political leanings from Facebook and prefer to express them privately, that is being reserved. When Yalies speak out vociferously on issues ranging from legalization of marijuana to reproductive rights and racial justice, but en masse stay silent on this particular episode of a long series of massacres in the United States, that is disappointing. Apathy contributes to anti-Semitism in the country at large — especially in the wake of Pittsburgh, the Yale community has become anecdotally guilty of this. My hope moving forward is that we can do better — that we continue to condemn hatred of all forms, regardless of who has fallen victim.

Robert Proner is a senior in Branford College. Contact him at robert.proner@yale.edu .