The older a place is, the more skeletons it has. Some of them lurk in closets and behind basement walls, but most lie underground. In New Haven, sometimes the dead are raised, but usually they’re underfoot.

“People picnic out there and have no idea what’s beneath their feet,” said Nick Bellantoni, the former state archeologist of Connecticut, talking about the central park of the city, the New Haven Green.

The Green has gone through three significant transformations in its nearly 400-year lifetime. Its upper portion was christened as the space for a holy temple, the center of a nine-square plan formulated by founders John Davenport and Theophilus Eaton in 1638. Its lower half served alternately as a jail, courthouse, marketplace, parade grounds and space for “great guns” to ward off the local Native American tribes, Pequots and Eansketambawgs (who are now referred to as Quinnipiac). There is some debate as to whether the Green might have also served as a meeting place for the entire colony in the event of the rapture, or “the Doom.”

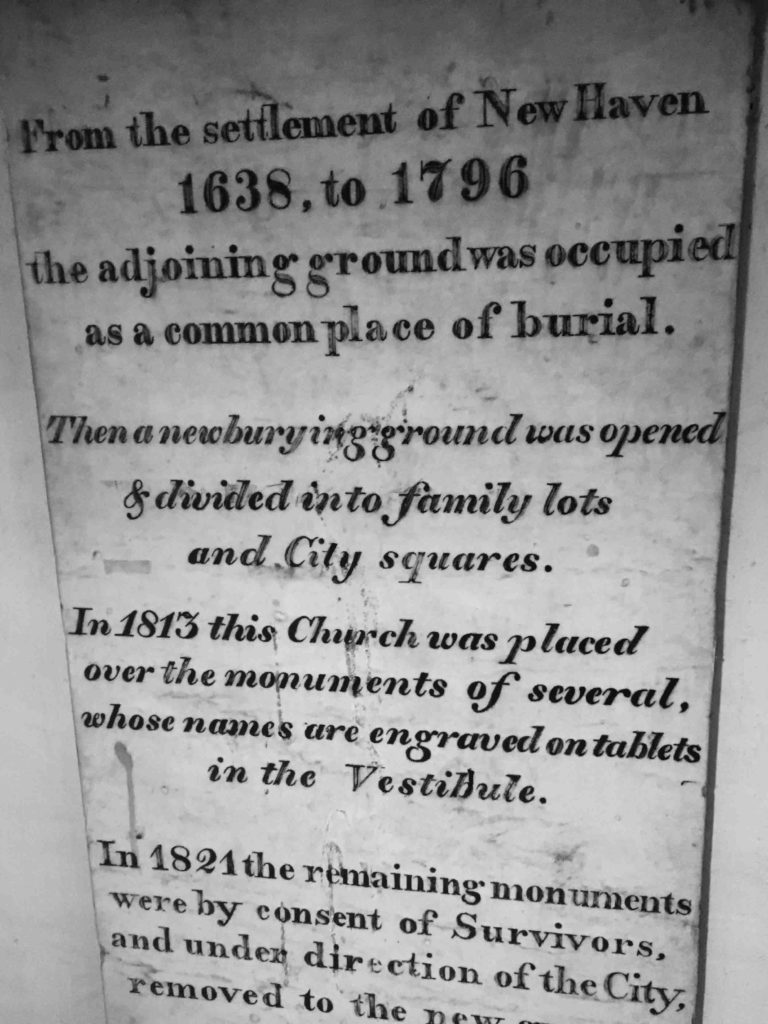

From the city’s founding until 1796, the upper portion of the Green also acted as a cemetery for its residents. While many of us walk across the space today without acknowledging the thousands of bodies buried underneath, the tour guides at Center Church consider the dead the centerpiece of their work. On Saturday mornings, those hunting ghosts or merely looking to satisfy a curiosity, enter the unsuspecting white building to see the crypt in its basement, which boasts of “recently” departed who are over 300 years old.

Standing in the Center Church Crypt felt somewhat anachronous; flickering fluorescent bulbs and metal pipes snaking across the six-foot-high ceiling caused the tombstones and stone tables to look like props in a movie set. As I gazed at the tombstones of some of America’s first settlers, I recalled a visit to colonial Williamsburg, Va., in which I saw a woman texting while on break at a bonnet shoppe.

Names and brief epitaphs were carved into the stone; typos were frequent and fixed by tiny letters careted above as death’s first draft. Skulls with wings, common Puritan motifs, rested above the names of the dead. Invented as a rejection of Catholic symbolism, they were replaced with winged cherubs after the Great Awakening, but still dominate the depths of the crypt today. It was the content of the inscriptions, though, that transported me back to the lives of colonial New Havenites.

“The painful mother of eight children of whom six survive,” read the epitaph for Sarah Whiting. She was described as “faithful, virtuous and weary.” I tried to imagine who she was. By the time she was born in 1669, the settlers in New Haven had moved out of the cellars they carved out from the earth during their first winter. Sarah was born in a proper house typical of the time, made from either wood or stone. Inside the iteration of Center Church that had existed then, she was baptized, maybe by John Davenport, who was New Haven’s reverend until the year Sarah was born. The Reverend Davenport, into his 70s, might have sprinkled water onto her forehead with his wrinkly hand, a passing of the torch from New Haven’s founders to the generation that would make the town their own. Sarah was probably not surprised when her two children died young — according to Bellantoni, a colonial woman in Connecticut could expect one-third of her children to die before reaching adulthood. Children’s names were like hand-me-down clothing: If her first son named Tobias died prematurely, his name would carry over to her next-born.

Originally, the crypt was said to have housed 137 bodies and souls, but an excavation in the 1990s revealed even more graves hidden beneath the visible ones. Today, an estimated 1,000 graves lie in and under the crypt.

The bodies decomposing beneath the Green as a whole number as many as 10,000. They reside there, mostly, peacefully. But every so often, strong winds have been known to unearth remains. After Hurricane Sandy swept through New Haven the day before Halloween in 2012, the remains of at least three people were lifted out of the ground by the roots of the Green’s famed Lincoln Oak. The team of archeologists led by Bellantoni presumes at least one of the individuals buried there was a child, because of a small clay marble found during the excavation.

Surprisingly, though, you are only given the Spark Notes version of this event on a New Haven ghost tour. When a guide named Colleen told the story, adding embellishments of questionable veracity, she said the bones had either been reburied or gone missing. In reality, the bones haven’t been reburied yet. They’re sitting in a Yale archaeologist’s office, which is maybe spookier.

The first time I went on this tour, I was one of three attendees: Timothy Pratt, who I later discovered worked as a chef at my old high school, was there with his wife. They weren’t exactly sure what had compelled them to fork over the $25 per ticket to shiver outside the New Haven Free Public Library while a man dressed in a floor-length black cloak and top hat talked earnestly about YouTube videos of a purported psychic he had watched, but they seemed to have a good enough time.

We stopped by a plaque to the left of City Hall. In 1839, 53 Mende African people who had been kidnapped and taken aboard La Amistad, an American slave ship, staged a mutiny. After they were spotted off the coast of Long Island, N.Y. and escorted back to shore, they were held in a cage awaiting trial in the very spot where the plaque now sits. The man in the floor-length cloak began to talk about voices and the sounds of rattling bars that some still hear, but I stopped listening when a man on a bike suddenly approached our group.

“’Scuse me, excuse me,” he said to our tour guide, whose expression grew with increasing discomfort. “You know, I didn’t know any of this s— until last month. My sister and my grandmother, they consider themselves African nationalists,” he said, emphasizing each syllable in “nationalists.” He told us that he speaks his own truth and doesn’t care what people think about it. Everyone else came here voluntarily, for a reason, he continued, but “my people,” he said, “didn’t have a choice.”

After a pause, our tour guide managed to spit out, meekly, “Thank you for sharing.”

“We still here!” the man yelled as he cycled away.

As we walked down High Street, passing the Skull and Bones building (“I hear they drink out of Geronimo’s skull”), our guide mentioned his day job as a justice of the peace. In a way, it made sense. There are points throughout our lives in which we allow ourselves to be guided by people we hardly know but who we assume know more than we do — reverends or rabbis and moyles when we are born; justices of the peace when we are wed; more reverends, rabbis and funeral home owners when we die; and ghost tour guides after we have been dead for a “spooky” amount of time, usually around a century.

After countless outbreaks of yellow fever in New Haven in the late 18th century, burying bodies on the Green no longer was a feasible option. As the population and diversity of the city grew, New Haven residents became increasingly secularized and no longer found it necessary to be buried in the backyard of their church. An empty plot of land off Grove Street became the new repository site for the dead, and the gravestones of those buried on the Green were soon transported there. If you visit the Grove Street Cemetery today, you can still see the old tombstones lined up alphabetically, leaning against the wrought-iron fence.

“Because they removed the stones, good grief, through time, people forgot that there was even a cemetery there,” Bellantoni said. “I suppose all the people that walk across the Green every day have no knowledge that there’s a cemetery underneath them.”

The trademark of time is forgetfulness. People are invariably forgotten, only to intermittently resurface in thinkpieces and ghost stories. If we remember John Davenport, it’s only for the Omni Hotel’s 19th-floor restaurant, currently offering glasses of beer and wine for $3.75 during Happy Hour to commemorate the 375th anniversary of New Haven’s founding. And what about Sarah Whiting’s history? The dead underfoot laid the foundations of the city we live in today, and walking over their bodies on the Green is spookier than fiction.