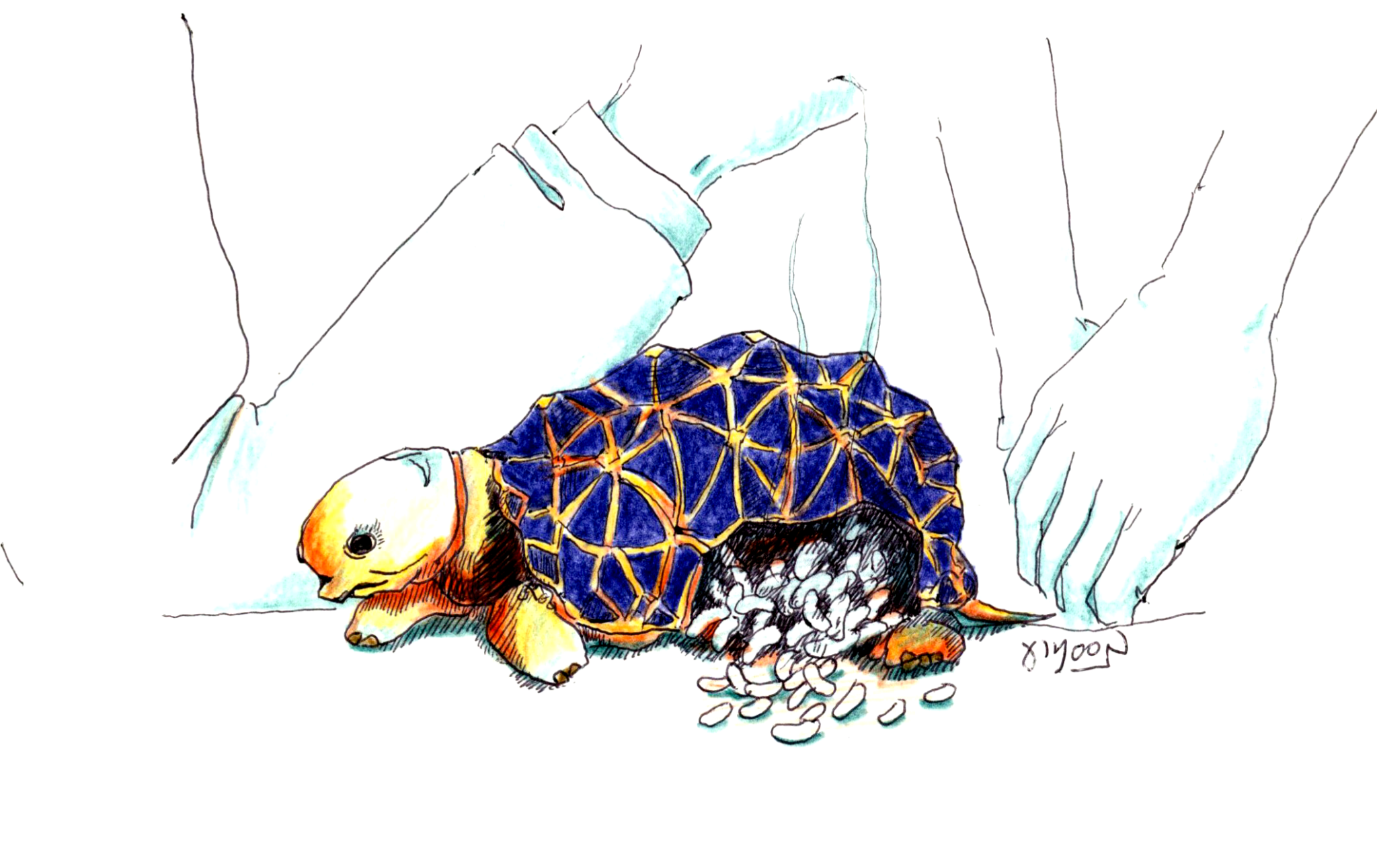

We were sitting around it in the basement, looking at the turtle where it lay, cracked and broken in a cushioned box. My sister had found it on the side of the road. A car must have hit it. It was dying, but it was still half-beautiful.

Seen from the left, the shell was perfect: a sunset orange with thin black marks inscribed, marks so precise and varied that they seemed an archaic language, like hieroglyphics or cuneiform. From the right one could see only the hole. It was huge and jagged. Around it, the shell had splintered. Beneath it the flesh writhed with maggots.

I sat on the left and my sister sat on the right. We said nothing. Darkness gathered in the corners of the room. It was her birthday, and she’d brought back a turtle.

I’m not the sort of person who stops to pick up turtles on the side of the road. Not the sort who’s troubled by roadkill, who feeds or even pities stray cats on the streets. But my sister is, and this was her birthday, and so I helped her. We called the vet, who laughed and hung up. We called our parents, who said the turtle would be happier if it died outdoors. We searched the internet and found nothing.

Near 8:00 p.m. my sister went upstairs. She came down wearing gloves and carrying tweezers. I held the turtle, she reached through the hole, and one by one tiny white worms dropped writhing onto the cushions. Afterwards we set out a cup of water for the turtle. We burned the maggots.

We did this until the basement stank of ashes and turtle dung. But there were too many maggots. It was as if the flesh were dissolving into a sea of maggots and we were trying to drain the sea with an eyedropper. After two days the turtle no longer struggled when my sister applied the tweezers. After three we carried the box outside, gently lifted the turtle out and set it down in a grassy space beside a pond.

When I tell my friends about the turtle, they often ask how young my sister was. I have a friend who writes poems. Once, in a poetry class, he listened to the instructor complain about the childish poems her students wrote about roadkill. “If you’re going to write about suffering,” the instructor said, “write about real suffering. Write about a close friend who’s died, a parent you’ve lost. Anyone whose experience of suffering is limited to roadkill doesn’t know what he’s talking about.”

Real suffering. Not like the suffering of an animal. The real thing.