“I think in an ideal world everyone would be asexual. Like imagine if everyone spent all the time they spend thinking about sex instead doing research. I think the total human utility derived from the invention of the wheel is greater than the total utility derived from sexual pleasure.”

In the week I have been texting James (whose name I have changed), I find that he likes to base his day-to-day rules and ideologies off of an ideal world. I remember him telling me that when it comes to political alignment, he was “much more policy-based on the horizontal axis” and “philosophical on the vertical axis.” He thought this juxtaposition of a more authoritarian but still socially liberal rule would result in the most effective economic policy. When I texted back, “And practically speaking?” he responded, “What is practically speaking?” Practically speaking, I was hovering over the send key after typing the following text in response to James’s comment on asexuality: “But what about all the pleasure and love?!” I thought about it for a second. For some reason, this text felt stupid, illogical and corny. So I tapped away at the backspace key and instead responded with a joke.

“Hmmm, disagree. Think about all that frustration in the car.”

“Frustration in the car?”

“All that driving frustration humans get really outweighs the benefits of the wheel.”

“Ohhhh. The wheel. I was thinking sex. Like car sex. This is why we need humans to be asexual.”

James and I met for the first time outside of texting and Tinder close to midnight on a Tuesday on the streets of the Upper West Side of Manhattan. We decided to walk without a destination, but in the direction of the Columbia dorms where he was staying. Throughout the walk, I pretended to understand his comments on philosophers and he pretended to not care about the drinks I had before seeing him. No games were played. There was no tug or chase. And so, I found myself leaving my college ID at the front desk and laying on a sheetless twin bed unbuttoning my Oxford shirt. I felt secure knowing we both shared a right-swiping motion with our index fingers on the cold screens of our phones. Just like that, we managed to erase worries about texting back, anxieties about asking each other out and all fears of unrequited attractions. With a single motion, we erased any risk that comes with falling in love. That night, I left with my phone in my hand, swiping on more men as I walked back to my place. It was a mindless walk.

This is not a love story about James and me. This is a story about my loveless generation.

A college friend of mine likes to yell at me when I start talking to any guy sober. “No dating till junior year,” she likes to say. She’s tackling the male-dominated fields of political science and economics while simultaneously redefining what it means to be a person of color in a sorority. She is, rightfully so, empowered by the many new faces like hers rising in our society. “Don’t get soft,” she says, spreading a widespread sentiment shared by many young students like us. In our generation, it seems that the empowering trends of independence and self-reliance grant you a seat at the cool table while shameless expressions of true love do not. We are taught that our youth is fleeting, our energy limited. Do now and feel later.

In a Snapchat conversation about fetishizing intellect, I found that James had a unique interest in Asian culture, often throwing in Chinese Pinyin into conversation. He drank too much “shui” the other day, instead of water, and oftentimes a stressful workday as an intern at Goldman Sachs isn’t just bad, it’s “bu hao.” I shared that I was reading Weike Wang’s “Omakase” in efforts to understand my reluctance to express love as a young Asian-American. His immediate response was about how people often accuse him of having “a thing for Asians.” He then questioned me about my upbringing and probed me with comments about the intersection between Asian culture and intellect. I found myself hesitating to respond, not because I was rubbed the wrong way by James’ sudden interest in my culture, but because I did not want to share too much. This was not going to be a love story. I convinced myself I had no interest in furthering genuine conversation. There was no point in telling him not to speak to me in Chinese. It was merely a hookup.

As a child of Chinese immigrants, I spent most of my upbringing in competitive environments. I went to prep school as a child in order to test into elite middle schools, high schools and eventually made my way to Yale. Stuyvesant High School gave me the opportunity to think about being Asian in a sea of yellow bodies. I quickly learned that I was not the only one who felt a lack of connection with my parents. It was a common story to say “I love you” and not hear it back. With an emphasis on societal ascension, to be successful meant to be better than everyone else. To be capable meant to not succumb to the basic flaws of human emotions. To be smart meant to be better than love.

In the close quarters of college, where hormones are high and the stress regarding professional success and development even higher, I found this same sentiment I had prescribed to being uniquely Asian to be rampant. One friend would tell me “We’re just hooking up. I like her but, we just can’t date.” Another would say, “Love is for the weak.” Beyond our emphasis on self-reliance, we apply intellect to emotional connection, treating it as another line on a resume that we must balance with everything else.

The consequences of this mentality are daunting. James wouldn’t know this and I don’t know if he will ever find out, but while he glorifies Asian standards of success and emphasis of self-reliance, I sometimes struggle to have conversations with my father about love. I can’t speak to him about how I feel, about love and boys, because I never experienced these emotions or sentiments from him. I watched him climb the ladder to provide a good life for himself and his family. I idolized this, appreciative and faithful that I could do the same. But now, my father comes home to a facade of myself, the person he was supposed to spend his prime time loving. It comes as no surprise to me then that Ryan Park in his article “The Last of the Tiger Parents” notes a current phenomenon in which second-generation Asian-American parents are ditching the “succeed-at-all-costs” mindset. But in my generation, among college students like me, we cannot afford to go an entire generation before realizing what we have lost.

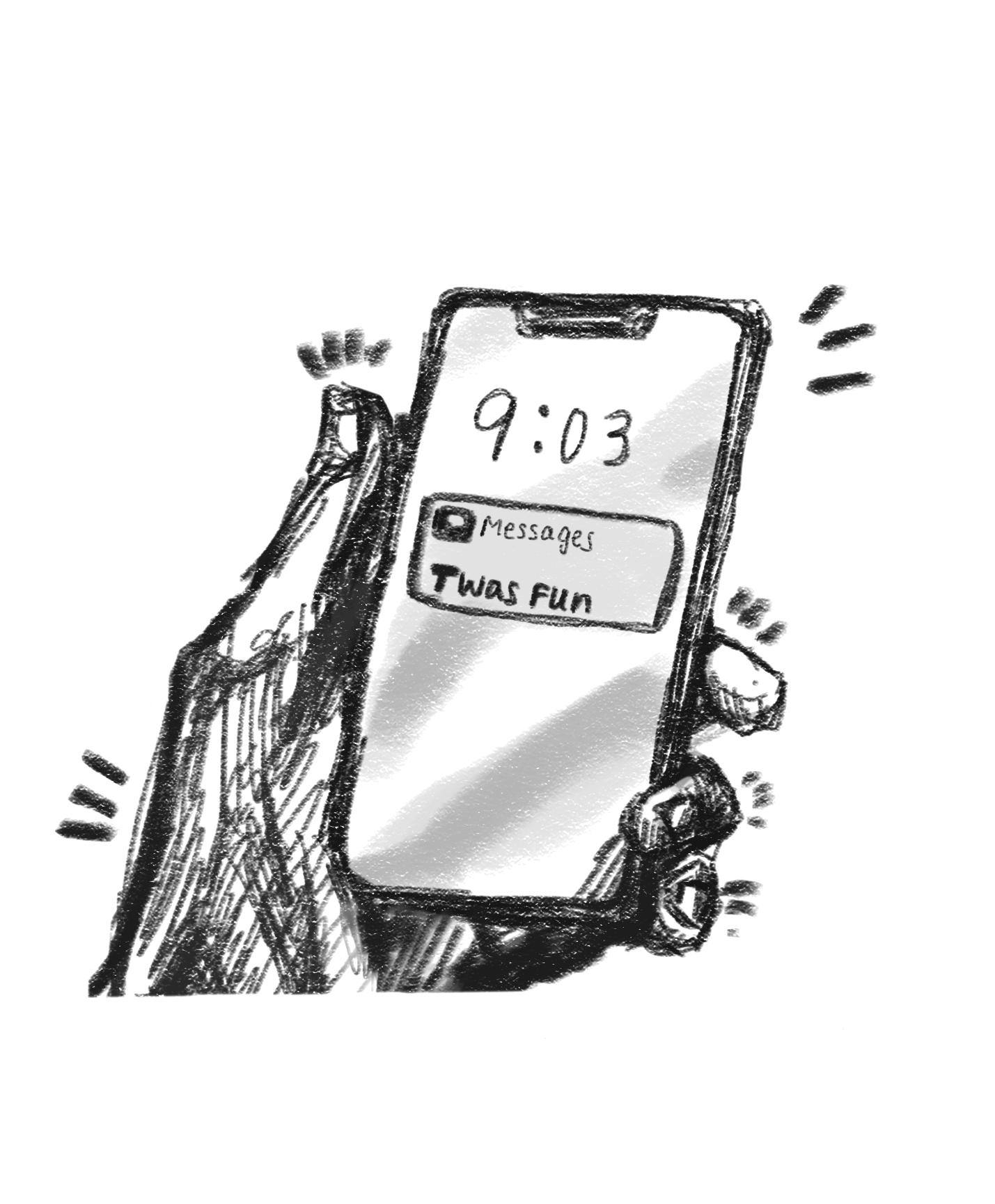

After our night, I texted James two words: “Twas fun.”

James was brave, exposing his deepest insecurities. “I feel like you will never talk to me again. I feel revealed, completed, understood. Good night.”

For once, I wanted to text back.

Practically speaking, I didn’t know how.

Alec Dai | alec.dai@yale.edu