On Sept. 26, a panel of graduate students and community organizations met to discuss New Haven’s Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion program, known as LEAD, which was launched in November of 2017 as a collaboration with New Haven Mayor Toni Harp’s office. While the aim of the program is to reduce arrest rates for those involved in nonviolent crimes such as drug possession and sex work, the panel said that the goals of LEAD are not being achieved.

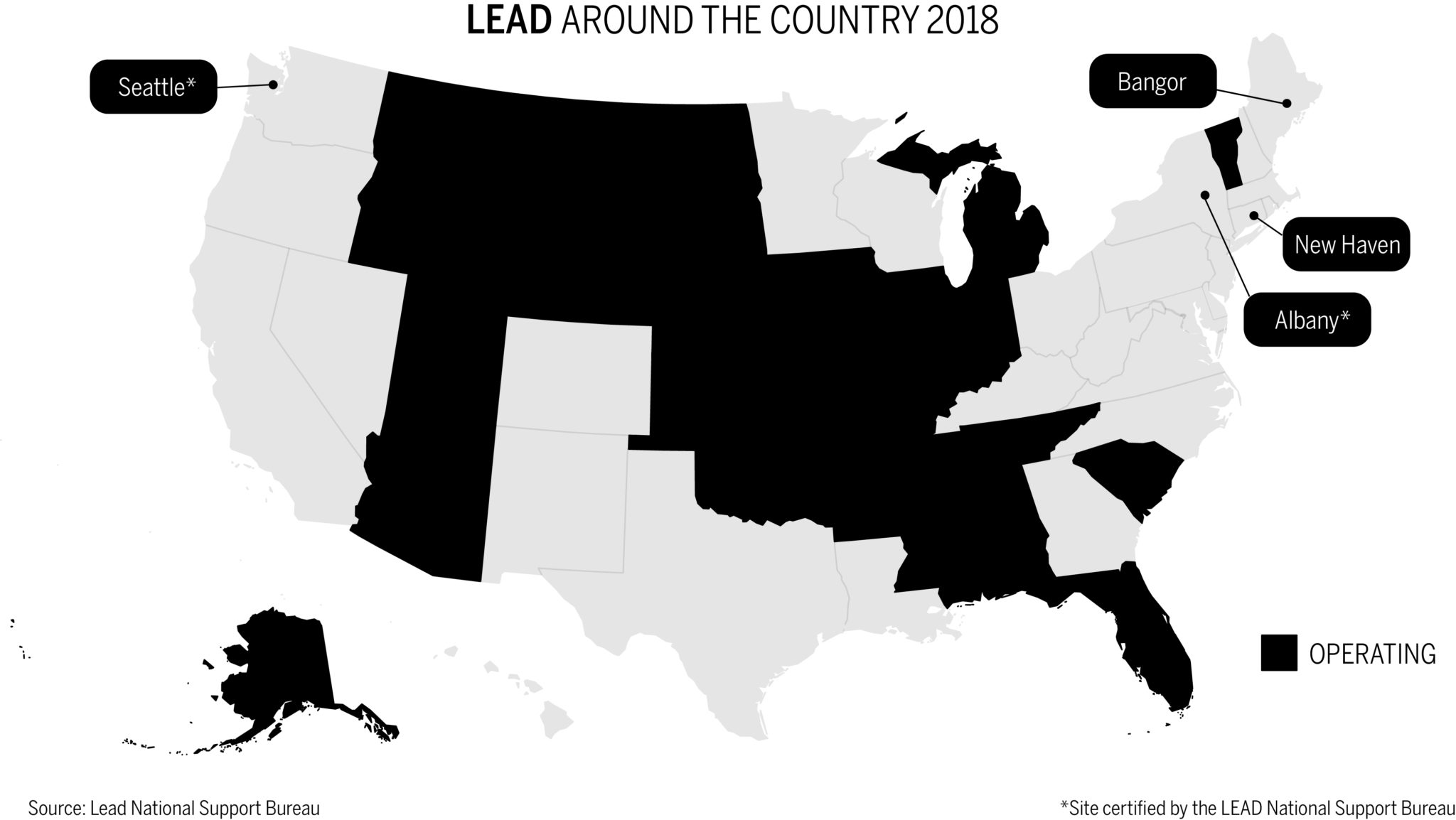

While LEAD is a relatively new program in New Haven, it has been fully integrated in cities like Seattle and Albany.

LEAD’s purpose is to divert those involved in drug crimes, non-violent misdemeanors and non-violent city ordinance violations to social specialists instead of the penal system. If a police officer of a LEAD-affiliated city encounters someone they would have cause to arrest for the above crimes, that officer can then offer LEAD as an alternative to arrest.

If the individual chooses LEAD, they will then have access to a range of social supports, including drug treatment and housing. However, if LEAD is not implemented correctly, divertees may not receive the help they requested and are vulnerable to recidivism.

Seattle was the first city to implement LEAD in 2011 as a reaction to its high recidivism rates, according to a 2015 report by the Seattle Times. According to a study done by the University of Washington, channeling low-level and repeat offenders through LEAD reduced the rate of subsequent arrest for similar crimes by 60 percent. And as of last month, LEAD in Seattle is expanding to Burien, which lies south of Seattle on the Puget Sound.

The LEAD model is now also operating in nineteen other cities scattered across the United States, including New Haven. According to the LEAD National Support Bureau, the program will be launching in ten other locations as well.

“An unplanned, but welcome, effect of LEAD has been the reconciliation and healing it has brought to police-community relations,” reads a statement on the website of the LEAD National Support Bureau.

Testimonials from community activists in New Haven suggest otherwise for those same relations within the Elm City.

Christine is a Fair Haven sex worker who did not wish to be identified by her full name, and who has been homeless for more than two years. “The police, there are one or two of them that have been phenomenal,” she previously told the News. “But as the child of a police officer myself, I find it appalling the way that we’re spoken to sometimes and treated.”

While the goals of the program remain constant, the integration of the program varies from city to city. This flexibility has enabled LEAD organizers in Albany to remove the police entirely from the diversion project, according to panelists at last week’s event.

Panelists discussed Albany as a more optimal example of the way LEAD is supposed to work compared to New Haven, both in terms of diversion by police and transparency with the community. While New Haven’s program was criticized for its lack of community involvement and information flow within the New Haven model for LEAD, those criticisms are much less applicable to the Albany program, according to Evan Serio, director of programming and advocacy at the Sex Workers and Allies Network.

“In cities where LEAD is functioning, like Albany, community groups have been at the table from the beginning,” Serio said.

Serio added that Albany community members were involved in the hiring of several LEAD administrative teams, as well as in the development of the program’s requirements for eligibility.

The New Haven LEAD program began in November of 2017 and remains in the first of its two-year pilot stage. While it is not the only pilot program experiencing administrative difficulties, program managers in other cities have so far been more responsive to the public about the challenges they are facing.

One such program in Bangor, Maine began in May 2017 as a response to the city’s opioid crisis and the constant full capacity of its jails, according to local LEAD case manager Ashley Brown. Like New Haven, community groups in Bangor were not immediate participants in LEAD’s implementation. However, in an interview with the News, Brown revealed that, while issues have cropped up within the first months of LEAD in Bangor, steps are being taken to refine the city’s model.

According to Brown, policy work for LEAD in Bangor is managed by a steering committee, consisting of representatives from the city public health department, a local shelter, a local substance abuse outpatient facility called Higher Grounds, the Bangor Police Department and the Brewer City Council.

While the steering committee aims to meet quarterly, Brown emphasized that she is working to create an operational workgroup that meets monthly or bi-monthly, consisting of police officers, representatives from the district attorney’s office and community organizations. Such a group would handle “more in-depth troubleshooting” and would work with those actually involved in the diversion process.

However, efforts to create similar groups in New Haven are either unknown or nonexistent. Both the News and panelists have attempted to contact the LEAD program in New Haven, but no official statement from the city about involving local organizations has been issued.

“Police officers aren’t going to know how folks are doing unless you have the time and space to have those conversations,” Brown said, referring to the workgroup. “So I think that provides more benefit to the program as well. We don’t have an operational workgroup at the moment, but that’s something that’s huge. I don’t know how we’d survive without it, and that’s something I’m working on right now.”

The problem with New Haven’s LEAD model, according to local activists, is that there is no process for incorporating the broader community.

Members of community groups like the Sex Workers and Alliance Network and the youth justice initiative My Brother’s Keeper have been working to obtain reports about the effectiveness of LEAD in New Haven, but such reports are limited. While it was initially reported at the panel that LEAD diverted 22 people, no specific record of those divertees has been made public.

Since LEAD was enacted in November 2017 in New Haven, the only records made public were LEAD’s original grant terms. Additional reports, released the day of the panel, contained almost no new information except for blank templates of divertees’ consent forms.

The New Haven LEAD program’s first report meeting for community organizations will take place on Oct. 23, nearly a full year after the program was launched.

Valerie Pavilonis | valerie.pavilonis@yale.edu .